My Bloody Valentine

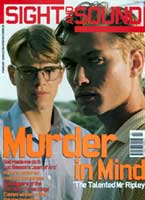

The hero of The Talented Mr. Ripley is a chameleon killer who wants to be his own best friend. Nick James talks to Anthony Minghella and Walter Murch about sympathetic outsiders.

On a hot day in July 1999 at the Jim Henson studios in London's Camden Town, Anthony Minghella is, he tells me, about to do something "tentative and experimental". Here he is, the shorts-wearing, Oscar-winning director of The English Patient (1996) inviting Sight and Sound into the cutting room of his latest film The Talented Mr. Ripley to see a few sequences. He and his collaborator, the revered editor Walter Murch, are properly genial and accommodating, yet there's an air of nervousness. On their side, it's because having previewed an early cut of Ripley to largely approving colleagues and advisors, they are now confronted with the US marketing people. "There's a concern that there are pansexual relationships in the film that might be unattractive to some Americans," says Minghella. It's at this point that he and Murch have decided to have their first formal press conversation and Minghella is worried their thoughts are only half formed. For my part, I'm anxious that Minghella may be simmering quiet resentment at his past treatment by critics, perhaps Sight and Sound's in particular.

For is this magazine not the epitome of the anti-Minghella tendency? I assumed so until I checked the reviews. Paul Tarrago, it's true, was pretty rude about Minghella's only 'Hollywood' movie Mr. Wonderful (1993), saying his "authorial ethos" was, "when emotions run high, make everyone act endearingly young" (to which anyone might reply, yes, but isn't that what people do when emotions run high?). However, while the S&S reviews of Minghella's first film Truly Madly Deeply (1990) and The English Patient were not exactly raves, they did quietly admire. This was a surprise because there remains a question mark over Minghella among British critics. Certain early lapses of taste - such as the unbearably fey scene in Truly Madly Deeply where Michael Maloney and Juliet Stevenson do indeed come over all childlike and start hopping along the South Bank promenade - earned him a vigilant antipathy among some commentators that's hard to shift.

This background of critical enmity was only partly deflected by the evident talent Minghella brought to The English Patient. Michael Ondaatje's allusive and slightly absurd novel of damaged souls thrown together by the backwash of World War II gave the director the chance to prove he could handle scenes as grand and imposing as the soaring emotions he was trying to describe. Yet though well written and superbly put together, the film rarely lets you forget its glossy packaging of international stars and exotic locations. You're always aware you're watching a prestige work, designed to dazzle. And for all its dark centrality to the film's explosive outcomes, the affair told in retrospect and performed so sensitively between Almásy the Hungarian explorer (Ralph Fiennes) and his English colleague's wife Katharine (Kristin Scott Thomas) is only slightly sour cream.

Which is not something you could say about The Talented Mr. Ripley. The most compelling reason for wanting to talk to Minghella was this choice of material. Patricia Highsmith's unnerving 1956 psychological thriller may be about enviable lifestyles but it is not about enviable emotions. It tells the story of Tom Ripley (played by Matt Damon), a striving, affectless young itinerant mistaken for an ex-Princeton student by a Mr Greenleaf, a rich shipyard owner. Ripley goes along with the mistake, pretending he knew Greenleaf's only son Dickie (Jude Law), who is now living it up on the Italian coast and refusing to come home to New York. Greenleaf commissions Tom to go all expenses paid to Mongibello to persuade Dickie to return. Enraptured by Dickie's playboy lifestyle, Tom ingratiates himself and confesses his arrangement with Greenleaf. But Dickie is fickle, and when, after weeks of what for Tom is exquisite intimacy with the high life, he shuts Tom out, Tom realises his desperate need to become Dickie Greenleaf himself. He does this in the only way left to him, by murdering Dickie and taking his place.

It's a cold subject, though it has plenty of 'hot' scenes for nervous Hollywood studio types to get nervous about. In particular there's a strong homoerotic tension between Tom and Dickie, despite Dickie's ever-present girlfriend Marge (Gwyneth Paltrow). Minghella and Murch show me four sequences, each of which immediately demonstrates how far from the novel the director is prepared to go. The first starts with Dickie and Tom larking about on a Vespa, then has Tom singing 'My Funny Valentine' â la Chet Baker to Dickie's sax accompaniment in a basement club, then Tom getting Dickie to do his signature so Tom can forge it, then Dickie in the bath playing chess with a bathside Tom.

This is probably the sequence that troubled the marketeers. Tom suggests he'd like to get in the bath, but when Dickie suspects him of some sort of sexual intent, Tom says he meant to get in it after him. The scene is filled with slightly sinister erotic tension with plenty of nudity and flashes of confused anger.

The jazz buddying is Minghella's own idea (the pair are not musicians in the novel) predicated on the irony that poor-boy Tom - who learns classical music because he thinks it's refined and only explores jazz to get closer to Dickie - turns out to be much better at improvisation than the rich dilettante. A second sequence reprises the jazz theme: Tom, in Rome for the first time, is standing in the doorway of a record shop waiting to visit the Colosseum, while Dickie is inside grooving to the latest jazz releases with his Rome pal Freddie. Dickie eventually emerges from his booth and suggests that Tom goes ahead, though Tom has heard him arrange a club visit that evening from which he is clearly excluded.

A third sequence shows an Italian religious ceremony where a statue of the Madonna is borne out of the sea, during which the corpse of a local girl suddenly bobs up. She has committed suicide because - as only Tom knows - of Dickie. Last comes the violent encounter between Tom and Dickie aboard a boat. Without the context of the rest of the film, the religious-ceremony sequence lacks something, but the fluent ease of the first sequence makes it clear that Minghella and Murch are crafting something powerfully inventive and the shock of the last confirms it. One thing Minghella and Murch are not prepared to do at this point is show me anything of Matt Damon as Tom playing Dickie after the murder (see the postscript after the interview for a view of that). Please be warned that the interview which follows reveals much about the plot that might spoil your enjoyment of the film.

Nick James: What has been your approach to adapting Patricia Highsmith's novel?

Anthony Minghella: The film opens in New York with a title sequence, but unlike the novel it's then centred on Italy. The screenplay began with 48 or so pages of America before Ripley went to Italy, but with each successive draft that gradually receded. I wanted to make sure the audience couldn't extrapolate what was going to happen. A lot of the novel is taken up with the police process, and if you strip away Highsmith's marvellously airless and claustrophobic treatment of it, her narrative beats don't stand up to scrutiny. They're covered with a wonderful prose gloss that makes you experience things without question which wouldn't work on film. Tom Ripley is a fascinating, complex, Camus-like character. But what I didn't respond to in the novel is its seeming lack of dramatic structure.

Then the end looks past its last page to the return of Ripley in sequels. Unlike in the 1960 René Clement film from the same source Plein Soleil in which Ripley gets caught, I was charmed by the idea of a central character who could commit murder and get away with it. It's not that I enjoy the amorality of that. I wanted to say that getting away with it is his punishment.

NJ: What have you added?

AM: There's a character called Peter Smith-Kingsley, played by Jack Davenport, who warrants a couple of mentions in the novel but in the film Ripley falls in love with him. He's a musician who is capable of loving Ripley for who Ripley is. In the screenplay Ripley says, "I'd rather be a fake somebody than a real nobody," and that's like a mantra around him. Then Ripley meets Peter, but in pretending to be Dickie Greenleaf he has already annihilated himself. I've added the killing of Peter at the end, and it's as if you've seen Ripley killing lust or desire or passion with Dickie and then killing the possibility of love with Peter. Ripley's ability to extemporise, to invent plausible stories in implausible situations, is his blessing and his curse. He can never be like he is.

NJ: The book is an intriguingly chilling choice for a director whose films are thought of as highly emotive.

AM: In the days when I was writing plays - in particular the last one, Made in Bangkok, which coincided with a series I'd written, What If It's Raining?, on Channel 4 - people said I was dark and acerbic. But I didn't feel that way any more than I now feel unduly committed to large gusts of emotion. Obviously I gravitate towards material in which there's a free articulation of feelings - I'm not ashamed of that. And Ripley's feelings seem to me to be volcanic: a constantly bubbling emotion that's suppressed but extremely present. In many ways he's the most feeling character I've been connected to.

You can only assume that your own taste largely collides with other people's. And I've always found it very likely to want to trade myself in for somebody else - I've often wished I was a different kind of writer, that the music I made was a different kind of music. So there's certainly common ground between Ripley and myself - the feeling that there's an easier, less fragile world being enjoyed by other people. Then when I met Matt Damon he said, "I know who this guy is." And many other people connected with the

NJ: Matt Damon seems a good choice to play someone so hard to pin down.

AM: Matt Damon is a revelation in this film. For an actor on the verge of being a big movie star to choose to do this part is already extraordinary, and then the absolute guile with which he approaches the character is amazing.

Walter Murch: You never feel him peeping out from behind the character and saying, "It's Matt Damon behind here just doing a part."

NJ: Why did you choose an English actor to play Dickie Greenleaf?

AM: I was obsessed with Jude Law being the right person from the beginning. It's rather the way Ralph Fiennes was cast in Quiz Show as someone who could play a well-to-do young American in the late 50s and early 60s. Most good young American male actors don't play that social territory very well, whereas a lot of British actors go there very naturally. There don't seem to be many Brahmin American actors in the way that, for instance, Gwyneth Paltrow is so clearly able to essay that territory.

Patricia Highsmith hated Marge. I read a letter in which she referred to someone as, "a vile creature, a Marge Sherwood type". She didn't care for Dickie either, but for me films which adjudicate are very dull. I've always been allergic to them. So I've always tried to force audiences to come to their own conclusions about characters. In the film Dickie and Marge are, by their own lights, perfectly agreeable people.

NJ: In the novel there's a sneaking feeling that Ripley might be interested in Marge.

AM: It's not the relationship in Plein Soleil where you feel Ripley wants the girl rather than the guy. Here you don't think he's in love with Marge, you know he thinks it would serve him well if she thought well of him. If we're going to have trouble with this film I know it'll be because of its darkness rather than its light - I mean, nobody will say we treat this movie with a light hand. I have this notion of it being a tragedy, purgatorial and about descent. We unravel this person, I hope with a certain amount of compassion, but it's a bruising event. It's not an easy film to watch - which may be the kiss of death for its commercial prospects.

NJ: There's a lot in the novel that's reminiscent of Hitchcock, particularly the emphasis on suspense.

WM: I don't think there's anything like it in Hitchcock. Strangers on a Train is maybe the closest. I thought about the suspense in terms of a tower of teacups. The film stacks cups and saucers on top of each other - sometimes you think they're bound to crash one way, then something happens and they lean in the other direction. In the end the tower is leaning as far as it can, but the film is over and you never see it fall.

AM: I've never written or been associated with something where there's such a singular point of view. But you can't avoid yourself whatever you do. When I was writing plays I wanted to be Howard Barker or Edward Bond, somebody really stern and analytical with a certain coolness. Whatever I did, though, you could always stick the thermometer into the bit of meat and it would be 68 degrees. Whatever its surface noise and whatever the bruising and remorseless tone, I'm sure this film betrays my chemistry at every point.

NJ: Why did you make Tom and Dickie jazz fans?

AM: In the novel Dickie is a not very good painter and has various discussions with Tom about painting, which made me wary of 'as interesting as watching paint dry' pitfalls. So because I'm obsessed with music and think that sound in film is as important as image, I made their argument a musical one. It's also a way of lassooing the period in that a lot of jazz players were living in Europe in the late 50s. Dickie has gone to blow his alto sax in Europe away from the claws of his father and Ripley is a classical musician who tries to learn jazz in order to have something to share with Dickie. But while Dickie sees himself as an existential beat person who lives by his own law and Ripley worries that he's a straight conservative who doesn't understand anything, in reality - just as it's Bach and Beethoven who were the great improvisers, not Charlie Parker and Miles Davis - Ripley turns out to be a great improviser while Dickie is a rather conventional guy sowing his wild oats. It's Ripley who has the jazz chops.

NJ: I remember a quiet Italy of ease and comfort in the novel - not a jazz fan's Italy.

AM: Because of my Italian blood I didn't want to go to Italy and just have lots of postcard views. And Italy in that La dolce vita period of il boom, as it's called, had changed. Ten years after the war they'd started to escape poverty and discover style and Vespas. So the film had to buy into that. The novel is based partly on Henry James' The Ambassadors, which is all about the idea of Americans becoming marinated in civilised European culture, whereas to me Italy, and particularly the south, is hugely pagan. So I tried to weave into the story a sense of Italy as a character acting on these people.

Actually Highsmith writes almost nothing at all about the places. There's much more about how you make a Martini, or adjudicating people by what drink they order in a bar. Where the bar was, who was there - so much about the striations of class and personality by choices of costume and hair.

NJ: What did you decide about Tom's sexuality?

AM: That's very interesting territory that I can't really work out. I decided Ripley is both. I think he's a virgin and a lot of what he's feeling is to do with a terror of what it means to feel physical interest. Also he tries to have a relationship with a woman and can't really carry it off. Whereas you do feel that when he meets Peter he could have a proper relationship. Even though there's nothing like that in the book, there are parallel episodes. That to me is what you have to do when you create material - create stuff that could have been in the novel. When you haven't got it right and there's something that's treacherous to the novel it feels as if you've begun to lose faith with what you started from.

Postscript: January 2000

Having now seen the completed film, I can say Minghella's overhaul of Highsmith is comprehensive. And he and Murch must have won their marketing discussion to some extent since the bathroom sequence is not materially altered, though I have the impression there's less of Jude Law nude than there was. The film grips you with claustrophobia; the plot is a narrowing of options for Tom always down to murder. It certainly does chill. But best of all is its tackling of a matter some claim doesn't exist - the American class system.

Despite his brilliant improvising, Ripley can't get it right. In a tour-de-force moment for which the Academy should post him a statuette right now, Philip Seymour Hoffman as a suspicious Freddie trips around what is meant to be Dickie's apartment (but is really Tom-as-Dickie's), flipping up his hands at the decor and braying viciously: "Tommy, Tommy, Tommy, Tommy, Tommy, this isn't Dickie, this is so bourgeois." It's here the film moves back through the novel to its own inspirations in Henry James. In Why Read the Classics? Italo Calvino says of one character in James' Daisy Miller: "He has been living in Europe too long and does not know how to distinguish his 'decent' compatriots from those of low social extraction. But this uncertainty about social identity applies to all of them - these voluntary exiles in whom James sees a reflection of himself - whether they are 'stiff' or emancipated." This is the tragedy of Minghella's The Talented Mr. Ripley - that Ripley, who fears sex as James did, could not find his place as the stiff among the emancipated.