Festivals

London Film Festival 2011:

The Sight & Sound blog

« Week one

Albert Serra: “I am the best one”

Albert Serra

Kieron Corless, 27 October

It’s always a pleasure to welcome Albert Serra, self-proclaimed ‘greatest director in Spain’, back to the LFF. I cherish the memory of seeing his stunning debut feature Honour of the Knights, a mesmerisingly aslant concentration and distillation of the Don Quixote novel and myth, here in 2006: it’s still one of my all-time favourite LFF screenings.

I caught his new film The Lord Worked Wonders In Me (his third film after 2008’s Birdsong) on an unseasonably warm Saturday afternoon at the ICA. The audience was sparse, but among the dedicated few were directors Yorgos Lanthimos and Ben Rivers, both big fans of Serra’s work. (You can read Rivers’ thoughts on the film here.)

The Lord Worked Wonders In Me, weighing in at 146 minutes, is paired with a much shorter film by Lisandro Alonso, Untitled (Letter for Serra). Together they’re part of a series of filmed ‘letter’ exchanges between directors commissioned by the Barcelona Contemporary Culture Museum (CCCB), which was inaugurated by Víctor Erice and Abbas Kiaorastami in 2006 and continued by José Luis Guerín and Jonas Mekas in Correspondence, also shown in this year’s LFF.

I met Serra to discuss the ‘Letters’ project and his own contribution (Alonso didn’t make it over to London this year). In conversations prior to shooting, the pair (long-term friends) agreed to make just one film each rather than a back and forth of ‘letters’, and as a point of contact between their new films, to refer to their own earlier works and push deeper into their respective aesthetics. Hence the return in Alonso’s film of a character from his 2001 debut La Libertad, Misael the woodcutter.

The Lord Worked Wonders in Me takes place in La Mancha, setting for Cervantes’ Don Quixote, the original idea being to shoot a road movie in that novel’s mythical imaginary landscape. What Serra and his actors and collaborators discovered was that that landscape no longer exists, if it ever did. “There were no interesting or beautiful things,” Serra told me, forlornly.

Instead they started filming in interiors – the cheap hotels they were staying in, or inside the van they used to get around – as well as in different landscapes. The idea morphed into something more self-referential, complementary to the aforementioned Honour of the Knights rather than related to the ‘real’ Don Quixote: a making-of for a film that doesn’t exist, or in fact is the film you’re actually watching – or as Serra puts it below, a making-of for all his previous and future films. Serra and co invite the viewer on a long, fascinating, sometimes arduous journey, one blessed with some exquisite moments and ultimately worth making the time for.

Alonso and Serra is a fairly obvious pairing to anyone familiar with the landscape of contemporary filmmaking of a more radical bent. The pair tend to be grouped with the Portuguese director Miguel Gomes, partly because they’re of the same generation – all born in the same year, according to Serra – and partly because they came to prominence around the same time, under the auspices of Olivier Père’s Quinzaine (Director’s Fortnight) programming in Cannes.

In truth, they’re all quite different aesthetically, with Serra most clearly positioned in the vanguard of a particular long-take observational cinema. What they have in common is more on the level of attitude and stance; a willingness to take big risks, an affinity for working with non-professionals, sometimes in the farthest reaches or most overlooked areas of their respective countries, and a proclivity for mashing up documentary and fiction to novel and exciting effect.

The interview below is my first encounter with Serra, already something of a legend of the contemporary filmmaking scene. I found him funny, engaging, provocative, opinionated, uncompromising. To his detractors he’s a loud-mouthed charlatan, to others a showman and much-needed wind-up merchant; there’s certainly no-one else quite like him in contemporary cinema. I’ve presented his thoughts verbatim; they emerged as an unstoppable torrent, but I’ve tried to structure them into more easily assimilable chunks.

On getting the commission

“It was a dream. They give you some money and say ‘do whatever you want’.”

On the ‘Correspondence’ project

“The idea was it should be like the others in the series (Kiaorastami/Erice, Guerin/Mekas). You send one letter, the other answers, and so on. But Lisandro and I are friends; none of the others knew each other before. We did, so it wasn’t about communication in our case, it was more about aesthetic affinity, and friendship. So we just decided to go deeper into our own aesthetics, and make our work in as honest a way as possible.

“It seemed childish to make small pieces; I wasn’t interested in what Lisandro was doing now. In the other couples, they are fake friends; they are trying to make this masquerade of communicating something, a masquerade of friendship.

“The idea for me was to make a free film, and the commissioners said ‘Okay, just do what you want; it will be one letter.’ I originally sent Lisandro a three-and-a-half-hour first cut, without subtitles, and he said, ‘Fuck, this is not a letter, it’s a monologue!’”

On his own filmed ‘letter’, The Lord Worked Wonders In Me

“In my case it was having the possibility to show the things I hadn’t been able to before in my films, because of aesthetic pressure or because they were deemed improper. The ludic side of the way I work is hidden in my previous films because of their formalism, but it’s an important element for me: it’s why I decided to make cinema, for fun, to make a break with routine daily life, which is getting more mediocre all the time. Cinema was a way of escaping this. Cinema is a social art that creates a certain ambience; it’s work but there’s also the element of friendship and family.

“But I also wanted to bear witness to something in this film – to a way of making films that is perhaps disappearing, because cinema is not financing this kind of approach, these kind of festival films, any more. Showing long works is important nowadays. I’m tired of stupid little things. I like to make something long, that requires time. I like to feel time, duration. Cinema should be this, making perception of time and space more intense. Daily life can’t allow this intensity of perception, of beauty. Cinema can make this happen, and for me this is essential.”

On how this film differs from his other films

“When you edit a feature film, you always ask yourself, ‘Will this work?’, and when you ask that you’re not thinking just of yourself but of the global concept of the film. You’re not thinking of the audience, exactly, but whether the film will be better or worse.

“In this film my idea was to avoid this and follow my own taste. It’s a joke ‘making of’ of all my previous features, and my future ones too, I hope. You never see a camera. You never know who is controlling the point of view; sometimes you have the sense that there’s no-one behind the camera, that it stands alone. You realise after a while that the film being shot is in fact the film you are seeing.”

On cinema

“In my case I don’t have a grand idea of cinema; for me it’s just another art form. I don’t have this dream of living inside cinema. I feel closer to 20th century art, even if I am a cinephile. I don’t feel the romantic idea of cinema. I don’t like cameras, I don’t l like shooting, I don’t like technical things. For me, far more than a game, cinema was a subversive way to change my life. But it could equally have been another thing.”

On using digital cameras

“My actors are always non-professionals, and they simply require more time. I don’t have money, and I like to shoot long shots. But even if I had money, I wouldn’t shoot on film. It’s impossible with my actors. It would be boring; it would be like working.”

On technical craft

“I never operate the camera, I detest it. Whenever I’m on the street and see someone shooting something, I hate it. Sometimes I look through the camera and check the composition, but only 5 or 10 per cent of the shots, when the cinematographer has some doubts.”

On working exclusively with non-professionals

“There are two main reasons. Working with non-professionals, I’m always discovering things, so working becomes more entertaining. With my idea of making films for fun, and this subversive idea of changing our lives, it’s more interesting, and the only possibility.

“Secondly, there’s something else that I discovered slowly when I was working, which is becoming a powerful idea in my mind: between you and the non-professional actor, you are alone. The manipulation by the director of the actor is direct. But with professional actors they have an imaginary in between you and them. In other words they have some model in their minds about how to act, or how someone did it before, or some techniques, visual or physical, they can use.

“I don’t like that, it’s as if you are writing a book and you are two… I don’t like books written by two. It can sometimes create complexity, but only in a few films; perhaps when it’s conscious and you play with that, like in Almodóvar’s films, perhaps it can be interesting. But I don’t want to work when I make cinema, I don’t want to have to study the imaginary just to make this actor work. Why deal with this, why spend days trying to solve this problem when with a non-professional actor it’s already solved? It’s losing time, it’s wasting energy.

“And I don’t like actors. As personal human beings, I don’t like the character of actors in general. Polanski said, ‘An intelligent actor is a paradox’. Acting is nothing, and they pay you. American actors get millions of dollars for doing nothing.”

On improvisation

“My films are improvised, there is no script. I always use non-professional actors I know, more or less, so I intuit how they will react. I put them in situations where I ask them to say or do something so I can more or less predict how it will develop. There is a beautiful quote of Picasso’s: ‘I don’t look for things, I find them.’ I know more or less what will happen. But they always surprise me too, and that’s what is beautiful: this manipulation of the actors goes in two directions.”

On his new film, Dracula

“It’s 90 per cent finished. It’s my biggest budget to date, €1.2 million. It’s not only Dracula, because I don’t like fantastic cinema, so I’ve mixed Dracula with Casanova. It’s a challenge; the line between sublime and ridiculous can be really really fine in this case. It’s risky, the film can fail, because it tries to mix different levels, different themes.

“And this is something you see to in filmmakers I admire, such as Miguel Gomes and Lisandro Alonso: the possibility of failure has to be real because otherwise it won’t be alive. Dracula and Casanova is a risk because they don’t match, so we have to solve that problem. Every film has to be a challenge and a new direction.”

On admiration for, and influence by, other filmmakers

“I like Sokurov, always, even if he makes bad films or failed films, because he takes risks. And you can’t spot any influences there – perhaps Tarkovsky, a very far-off echo. I like some Béla Tarr films, even if they are too emphatic for my tastes. I like some of Hong Sang-Soo’s film, even though he’s far from my style and interests. They’re so simple and yet so complex, a beautiful portrait of the people of the world nowadays.

“But they don’t influence my work. I try to be as particular and as alone as possible. It makes no sense to be influenced by others. Be influenced by music, by writers, but not by cinema. I find it vulgar to be influenced by filmmakers. Compared to a writer, nowadays a filmmaker is more like an actor. You have to keep these serious roots. Like Buñuel, who was coming from surreal art: he was not a filmmaker but something else; part of the world, part of the art world, part of the thinking of the time.

“I try to be, but today it’s more difficult, everybody is more isolated. It has to be ambitious in some sense, in the past sense that has been forgotten. It has to be honest. I never go to the cinema. I don’t like Tarantino, for example; he’s very bad. Maybe Death Proof. Sokurov was very angry with Marco Muller when he made Tarantino president of the jury in Venice: how can you put this idiot as president of the jury? For Sokurov, art and cinema are sacred, and I am closer to this idea.”

On artists

“I’m a man of the past, but it’s something I don’t like. I don’t like this nostalgia, this melancholia. I don’t like cinema in a romantic way, but I like the romantic idea of the artist in general. Artists are different to other people. In my mind, only artists can see beauty; for that reason they are different.

“Spectators can have the intuition that in the film there is beauty, but they really cannot see the beauty. Only other artists and filmmakers can really see this pure beauty. And for me the artist is sacred, because they can perceive beauty directly. This romantic idea is very important. It makes no sense to me to avoid this for the sake of being more successful or more popular.”

On Lisandro Alonso

“I don’t know if he is this kind of artist, but I like his work. Los Muertos is my favourite film. I don’t like Liverpool; it’s becoming bad. But the main reason Los Muertos is so good is because the main actor is so charismatic. It’s simple. Why don’t other people do that? Take this man. The man is so charismatic, the intensity is growing, growing, through all the stages of the film, even the psychological and dramatic aspects are growing due to the charisma of the actor. For me it was very impressive. La Libertad is too repetitive and formalist for me.

On British cinema

“I hate all British cinema. There are no British filmmakers I like, none at all. I hate Michael Powell, especially Peeping Tom; it’s one of the most horrible films I’ve ever seen. Derek Jarman is very bad, but there are some small, crazy things in there I like. The worst is McQueen: he is the devil, an absolute devil, because he is making people believe he is making artistic films, and it’s bullshit. But film criticism, film taste here in the UK, it’s not really respectable. It’s like being in a province. It’s a small cinema for me.”

“Nowadays the only city where you get proper distribution in cinemas and where they show most of the films from Cannes is Paris. I don’t like France, or French people, and I’ll never live there, but in cinema terms it’s the only capital that’s not provincial. London is provincial, it’s terrible. Last time I was at the festival the audiences were very bad. People didn’t understand the film; they thought it was a joke.”

On Spanish cinema

“I am the best one. I hate Erice. Those are films for children. And I don’t like films with children in them, like Spirit of the Beehive. Saura has a few good films, Bardem too; Berlanga is more folkloric. There are a few in the past. Buñuel is the greatest figure; for me this is the true spirit. All the others are just filmmakers.”

On American cinema

“I like American cinema of the past, but it’s the same problem as with independent cinema today: I hate it all.”

On cinema’s future

“The space for cinema is shrinking. This is what I am now dealing with, but I don’t know what I’ll do exactly. Perhaps the art world, but I don’t like the art world.”

Mystic Mathieu:

Amalric’s The Screen Illusion

Davina Quinlivan, 26 October

Mathieu Amalric delivers an arresting performance as violinist Nasser Ali in this year’s LFF premiere of Chicken with Plums (Poulet aux Prunes), Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud’s follow-up to their acclaimed Persepolis. His fourth directorial endeavour The Screen Illusion, meanwhile, takes the shape of an adaptation of Pierre Corneille’s meta-theatrical seventeenth-century play L’illusion comique (The Theatrical Illusion).

Amalric’s On Tour (2010) traversed France through the eyes of a burlesque dance troupe, winning him the Best Director award at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival. The Screen Illusion features a different ensemble of performers, gathered from (and indeed commissioned by) Paris’s prestigious Comédie Française, aka La maison de Molière.

Corneille’s original play has desperate patriarch Pridament seeking out a magician to find his missing son Clindor, who is observed through the gauzy apparitions of a crystal ball. (Pridament is then repulsed by what he sees of his son’s pursuit of wealth and power, sex and love.) In Amalric’s film the action is transposed to the Hotel du Louvre, and the all-seeing eye is provided by a concierge with keys to the hotel’s subterranean CCTV surveillance room.

Michael Almereyda’s 2000 Hamlet had Ethan Hawke prowling late-night shops while reciting some of Shakespeare’s most enduring lines. Almaric’s enmeshing of the two art forms is more convincing; the play’s rousing soliloquies are convincingly and sensitively handled, while the use of surveillance imagery to reframe Corneille’s themes is more self-reflexive and cinematically assured – comparable with Andrea Arnold’s Red Road with its mise en abîme of multiple CCTV screens.

The screens and interfaces scattered throughout the film – surveillance equipment, mobile phones and computer monitors – not only update the play to the modern era but also emphasise correlations between the mysticism of crystal ball-gazing and the power we invest in the image, technologically produced or otherwise. When Predament ‘sees’ his son’s execution by rival businessmen on the roof of the hotel, the concierge’s prescient warning about the authenticity of the image and our potential for fatal misinterpretation – revealing another set of gleaned views that show Predament’s son to be alive – sums up Amalric’s fascination with the visual language of film and the screen’s reign over all.

Five (not) by Ben Rivers

Chick Strand’s Artificial Paradise

Kieron Corless, 26 October

Ben Rivers’ brilliant first feature Two Days at Sea has been one of the most warmly received films at this year’s LFF, completely selling out NFT1. And in an inspired pairing, his new short Sack Barrow also screened in the festival alongside two of the San Francisco film artist Nathaniel Dorsky’s latest reveries.

S&S invited the former Brighton Cinematheque programmer to share his thoughts on his festival viewing. And so on Sunday of the festival’s final weekend, Rivers and I emerged from the Chick Strand programme blinking into the Southbank’s unexpected sunlight to munch on a burger and watch kids apple-bobbing while he mused on his following highlights.

Intimate Vision: Films by Chick Strand

“This was my pick of the festival even before it began. I’ve seen some of her work before, including a few in this programme.

“The one about the missionaries, Mosori Monika, was really great – I liked the way Strand was gently criticising them, but in a nice way, not in a full-blown, dogmatic, look-what-these-people-have-done kind of way. She looked at the situation from both sides.

“She seems like a very loving, warm filmmaker, and completely unashamed about that. I think that’s what I admire about her; her films are so intimate. And they way she shoots is so close – in Artificial Paradise, there are no establishing shots, it’s just straight in there, the skin and the warmth, the body. It’s very beautiful.

“And I loved the sound work in Kristallnacht. The way she collages sound is incredible. It’s what I aim to do, but she pulls off those shifts so beautifully. The image hardly changes, but the subtle shifts in the soundscape completely change what you’re looking at. It’s fantastic.

“As a programme it completely lived up to my expectations. She was linked to Bruce Baillie: they both used to go down to Mexico, and were very much catalysts for each other. They started up Canyon Cinema together. Baillie made some amazing films down there – Valentin de las Sierras is amazing. It’s similar in some ways to what Strand does; he’s basically filming a community, with a long, macro telephoto lens so you can get in close but from a distance, which creates this non-stop movement in the camera.”

The Lord Worked Wonders in Me

+ Untitled (Letter for Serra)

“Not many people went to see this, and there were even fewer at the end. The Q&A was fun: six or seven of us went to a back room in the ICA.

“The Alonso (Untitled (Letter for Serra)) seemed like a perfect nugget. It’s what he does really well, playing with these real, non-actor characters who are just doing things that they probably ordinarily do, but also placing on them this much older history. And then there was this distancing thing with the guy reading the text, and telling the others to follow him down this ominous dark path, and who knows where that’s leading. It felt pretty perfect; I really loved it.

“Albert’s film afterwards struggled to keep pace with that. I enjoyed it and thought it was quite funny; I laughed quite a lot and could see what he was getting at.

“I liked the idea that he just wants to let the camera roll, and film these people with whom he’s spent so much time with – and who he’s controlling most of the time, however much he says he isn’t. There’s an apparent absence of control, but there can be control in that, which is what I do too. You set up a situation where you also allow people to do their own thing, so there’s a chance things can happen. But it’s still a decision to do that.

“This film was an opportunity to let the camera roll and see them do their thing, but it outstays its welcome. It goes from funny to frustrating, and not in a constructive way. I was glad I stayed till the end, though: there’s a part-payoff. The ending is lovely: the song, the road, the continuation of their travels.

“It could be that digital cameras make you a bit more self-indulgent. I like it about film that you have these definite limits to work within. But a ten-minute shot can be indulgent too.

“Indulgence makes me think of eating cakes – it can be a good thing. Serra’s other films have these really long shots, but they make a lot of sense, whereas in this film the long takes didn’t all make sense. When do you turn the camera on, when do you turn it off? There was a really good long take where Sanchini and Quixote are sitting at the end of a corridor in a hotel. A lot happened in that; I don’t know how long it went on for, but it seemed a long time.

“There’s this dialogue Quixote has with Sanchini about loving him and wanting to marry him, but then he keeps going off to the toilet too much. Those things sometimes suffer when you have another ten minute take beforehand, which has killed your enthusiasm a bit. I still think he’s a great, fascinating filmmaker, though.”

Sleeping Sickness

“This was one of the highlights of the festival. I came out of it with my girlfriend and we were going, “Wow, that was really great.”

“I think that’s partly to do with having seen the Chantal Akerman film [Almayer’s Folly] a couple of days before, which felt a bit stodgy. I’m a big Akerman fan, but there’s something not working in that film at all. It’s also this colonial, washed-up outpost, washed-up person, stranger-in-a-strange land kind of thing, but it’s very hard to buy the characters, to believe in them, even though it’s so beautiful and amazingly done.

“Whereas with Sleeping Sickness, I really believed in those characters, and liked the way he was playing with the tricky politics and moral questions of what it means to work in aid in a third-world country. He was leaving almost as much space as he possibly could in between spoken lines, in between any kind of exposition: there was so much ambiguity about what was going on.

“I really appreciated the amount he pushed that ambiguity, allowing the politics to be read from so many different angles. And it was very beautifully constructed, beautifully shot and edited, with lots of dark passages.”

Faust

“I loved it. It’s completely stuck in my mind. Actually, while I was watching it I was thinking, “this is way too talky for Sokurov.” I was expecting loads of space, but he went in the opposite direction, and after a while I just had to go with it.

“I really like a lot of his films, although I’ve not seen any of his documentaries. Days of Eclipse is probably my favourite; Mother and Son is great. And all the ones in this series too; Taurus is fantastic. And what a great decision to put Faust at the end of the series. It was so dense, I need to see it again.

“I was surprised at how fast cut it was – shots weren’t held for as long as I thought they’d be. It was hard to keep up with the dialogue, the noise and the changes of image. The scene in the baths with all the women, when the devil gets naked and they’re laughing at his cock, is really brilliant. I think it’s a film to watch more than once, but then most things you should watch more than once.”

Gabriel Abrantes

“I’m a big fan of Gabriel’s. He’s a pal. We met a couple of years ago at IndieLisboa, where i gave him a prize for A History of Mutual Respect, so then he had to become a friend, he had no choice.

“That film is brilliant, perfect. It’s a very confident piece of work for a 26-year-old. But it should be ‘Gabriel Abrantes and collaborators’, because all his films are made with other people. Daniel Schmidt seems pretty key to what he’s doing at the moment.

“The films are full of ideas, they’re quite precocious, and – a word he likes to use – aggressive. Aggressively trying things out, they do try out loads of different ideas. Palaces of Pity is not as neat and compact as A History of Mutual Respect. It’s sprawling, and that could be a criticism; maybe he’s trying to do too much with it. For me, though, it’s not a criticism. I think it’s great they did it, and it’s great to put all these things together – a dream of the grandmother set in medieval times, which somehow talks about Portugal’s history and guilt, which is then being passed on to these teenage girls who just want to party.

“The ambition and scope is astonishing. They’re making films really cheaply, but they look amazing. They managed to persuade the army to lend them a helicopter to do helicopter shots. They’re enterprising and inventive, and for me that’s what cinema is about. Gabriel is very smart. When I saw his work, as a slightly older filmmaker, my initial impression was jealousy, and that’s good. I really wanted to know this guy; it’s really exciting what he’s doing and I can’t wait to see what they all do together in the future.”

Around the world in 14 films

Volcano

Nick Hasted, 26 October

I favour films from countries I love, which finds me first at the London Film Festival’s Icelandic selection. Arni Olafur Asgeirsson’s Undercurrent and Runar Runarsson’s Volcano both look beyond cosmopolitan Reykjavik, the former opening out Otto Geir Borg’s play to take a crew of sharply sketched misfits into the Atlantic on a rusty old trawler. A fatality on their previous voyage intrudes in flashback, and the claustrophobia, comradeship, humour and violence of this traditional occupation are well-caught, as rain and waves lit by the ship’s lights lash it.

Three of the ‘crew’ joined the director for a Q&A, cheerily out of character as they were asked what safety precautions stopped them being swept into the roiling Atlantic. “Our hands,” one explained, demonstrating a firm ship-rail grip. Undercurrent was intended as an elegy for what had seemed a dying way of life in Iceland’s brave new world of banking buccaneers. “Now we’ve gone back to fishing,” Asgeirsson laconically noted.

Volcano begins in the heart of Iceland’s reality, with 1970s footage of the hell-yellow sparks of volcanic eruptions on far-flung islands forcing their inhabitants to evacuate. We meet one of those evacuees, Hannes (Theodor Juliusson), on the day of his retirement. With his Father Christmas figure and beard, he seems a sullen ogre to his wife and middle-aged children. But when, still thinking himself a fisherman, his old tub almost sinks under him, the shock brings to the surface the unspoken love between him and his wife Anna.

Runarsson sets out the realities of old age, from sex to death, with unobtrusive truth. Juliusson’s performance is devastating, mingling stubbornness, loss and nostalgia with soft-voiced dignity. With his boat parked uselessly in his suburban Reykjavik garden, and his longing for a lost rural life, Hanne is emblematically Icelandic. But Hanne (and the camera) settles his gaze on slides of his young married life, the local detail makes his inevitable condition more moving.

That’s a strong showing from a country with a population the size of Coventry’s. From Norway’s more established film culture, Oslo, August 31st did its bit for Scandinavian melancholia, following a heroin addict around town on the last day of summer. The fragility of his recovery is chipped away by constant temptation and shame. Cool, clear summer light and quietly rational characters keep audience depression at bay.

“Why is it so sad? Is it only these people?” director Joachim Trier was asked afterwards. “You should come to Norway,” he half-joked, later suggesting a “double-shame” to failing in such a privileged place. He also spoke up for 35mm film, “the most beautiful way to document what’s in front of you” – in this case the “strange, hidden beauty” of his home city, vanishing under redevelopment as he filmed.

Nick James has written about the disappointment of Oren Moverman’s James Ellroy-originated bad cop film Rampart. When Moverman took the stage afterwards with Woody Harrelson (star of this and their previous collaboration The Messenger), he described the film he thought he’d made, and why it honourably fails.

Ellroy’s script was, he said, “out of control”, requiring “the biggest studio film ever made”. Overman’s extensive rewrite involved a deliberate “clash of agendas”, working out from Ellroy’s intention to “exonerate” the corrupt 1990s LAPD, personified by Harrelson’s bad man with a badge. Israeli Moverman found an outsider’s perspective on a “fucking hot” city where interiors (and so his film) are defensively dark, and anyone might go violently mad.

This was all fascinating, but couldn’t compete with Harrelson (excellent in Rampart, especially in his too few scenes with Robin Wright, who’s reliably riveting on her own downbound train). “The last thing you want after a heavy film is to struggle to make conversation with some drunk bastard up here spouting nonsense,” Harrelson observed, admirably summing up the average Q&A experience. Tugging his collar open and happily buzzed, he freewheeled from then on with a wicked glint in his eye.

Co-star/producer Ben Foster added his own undiplomatic barb when a woman mentioned the ending left her “dissatisfied”. “When were you last truly satisfied?” he snapped back. “I’m with my husband,” came the reply, “so I can’t really answer that.”

That was my Hollywood highlight. Two documentaries caught the beginning of America’s 1960s counter-culture, and one of its ends. Alex Gibney’s “immersive documentary” Magic Trip finally edits Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters’ copious footage of their 1964 trans-American ride on their psychedelically painted bus ‘Further’, with On the Road’s speed-rapping hero Neal Cassidy at the wheel.

Kesey had shown me the reels when I interviewed him in 1998 in Oregon, where the Pranksters had gone to ground. His ongoing inability to finish the film was part of a wider failure; when the acid-tripping crew accidentally ‘integrated’ a black-only Southern swimming area, they ran a mile on realising their mistake. Kesey was always as much redneck as hippie, and the Pranksters had largely pulled up the drawbridge on their rump country kingdom when we met. Kesey, though, flashed charisma and mischief, and the film catches both him – a blue-eyed young Brando – and the pre-comedown American 60s at invigorated peaks.

Darwin

Far more rugged American individualists are to be found in Nick Brandestini’s Darwin, the name of a former silver-mine boom town in California’s Death Valley, population now just 33. Each character is a documentarian’s dream. It’s “a place where government and commerce has all but evaporated,” Brandestini notes, a Dodge City in its last days, which even the most hard-headed here believe will end soon; the apocalypse is due, the otherwise acerbic postmistress says, next year.

Like Kesey’s gang, these are cowboys and hippies, libertarians and survivalists; extreme Americans. A stoic ex-miner who has been in Darwin since 1953 remembers its wild days, which did for his wife Lucky, killed in a bar-fight. “All we’re here to do is consume and waste,” an old anarchist, one hand useless since a nearly fatal OD, states of the unfriendly country beyond. “Everything’s set up to be ugly, and I don’t want to be part of it.” Brandestini lets the eccentricities pile entertainingly high, making the crowd I saw it with howl. He also leaves everyone their often tragic dignity.

The same could be said of Lawrence of Belgravia. Paul Kelly’s film was flagged up for 2006’s LFF, making this documentary as much a triumph over adversity as the music of its subject, ex-Felt and Denim singer Lawrence, who is shown in a state of raw, lank-haired poverty, making pop as a matter of survival. A flurry of documents, detailing huge rent arrears, heroin addiction and homelessness, summarise his harsh recent life.

“The only way I can carry on making music is that I’m insane,” Lawrence explains. A flaw of the film is that the raw chunks of music it shows him working on give little hint of his ability; ‘The Osmonds’, his majestic reverie on the 1970s, is cut off too soon. His dry Midlands wit and resilient childhood dreams of stardom on Top of the Pops (which he has outlived) sweeten what would otherwise be an uncomfortably voyeuristic tale.

The British film causing the biggest stir is Carol Morley’s Dreams of a Life (written about in Sight & Sound’s November issue; there were long queues for returns at a sold-out NFT1 screening. I haven’t seen it yet, but can put in a word for Dexter Fletcher’s directorial debut Wild Bill. A duplicate ticket found me sitting in Fletcher’s seat, alongside the cast and Jamie Oliver. An usherette gave me the bum’s rush with such panache I barely noticed until I was deposited in the back row.

The Essex and East London-heavy audience meant this tale of a Stratford hard man (Charlie Creed-Miles) reconnecting with his kids on a rough estate got the familiar laughs it deserved. Copious swearing, crack-smoking and child drug mules make it ripe for dreary social realism, but this is actually a very well-observed and performed, sharply funny family film. Just not for the sort of family the LFF tends to attract. Fletcher can’t find his way out of the bind he puts his characters in without fairytale contrivance. But his film, which has UK distribution, deserves to be a sizeable hit.

Two last stops on my tour: the Dreileben trilogy, also featured in S&S’s November issue, is a haunting achievement from Germany, arising from discussions between directors Christian Petzold, Dominik Graf and Christoph Hochhausler on what their country’s cinema could be. Each film radically shifts in perspective as an escaped killer goes on the run but, made for German TV to avoid the ‘festival film’ ghetto, this is no cold experiment. Watching Petzold’s Dreileben 1: Beats Being Dead on a preview DVD in my flat alone at 3am, I was so appalled at an unexpected crime that I cried out and reached towards the screen, to rescue the victim. It had the shock of seeing someone hit by a car. It’s to be hoped Dreileben gets some sort of proper release here.

Finally, Nanni Moretti’s We Have a Pope is evidence of the growing cultural criticism in Italy’s newly confident, perhaps soon post-Berlusconi cinema. It follows the election of a compromise, unexpected candidate as Pope, leading to his mental breakdown and visceral rejection of a role supposedly ordained by God.

French veteran Michel Piccoli’s performance as an old man first catatonic with shock, then going on the lam in Rome – a king secretly abroad among his people, trying to remember who they are – attains broken tragedy. Moretti’s own scenes as a liberal psychologist who keeps the cardinals busy with a volleyball tournament outstay their welcome. But as writer-director, he fashions a careful exploration of Catholic faith today.

So, by the way, does Alice Rohrwacher’s debut Corpo Celeste, intimately observing a 13-year-old girl’s rejection of a small Southern Italian parish’s claustrophobic rites. And a quick word for Andrea Molaioli’s The Jewel, a true-crime thriller about a venal, doomed Italian corporation, with Il Divo’s star Toni Servillo and some of that film’s swagger too. Italy is coming into its own towards the LFF’s end.

The book of cult

Häxan (Witchcraft Through the Ages)

Jane Giles, 24 October

To launch the publication of 100 Cult Films (BFI Palgrave Macmillan), the London Film Festival presented a panel discussion at the BFI Southbank, illustrated with clips, about what makes a cult film. The book’s co-author Xavier Mendik appeared alongside FrightFest’s Alan Jones and myself (as former Scala cinema programmer), with film journalist Damon Wise moderating.

Arranged alphabetically from 2001: a Space Odyssey to The Wizard of Oz, Mendik and Ernest Mathijs’s accessible, scholarly guide aims to list the most influential titles from across a broad range of genres and nationalities, focusing on the films themselves rather than their context or audience. In doing so, 100 Cult Films moves the arguments on from Danny Peary’s three-volume benchmark studies Cult Movies, published in the 1980s. The panel noted that the book grapples with concerns such as whether cult films are a genre in and of themselves and if blockbusters such as Star Wars and The Sound of Music can occupy the same terrain as Debbie Does Dallas and Cannibal Holocaust (which they clearly can, as all are on the 100 Cult Films list).

The book also picks out the common elements of cult movies – transgression, abjection, freakery, utopia, ‘badness’, intertextuality, irony, and the fact that so many of them deal with themes of time (travel and ending), extreme forms of sex and violence, religious cultism, bad drug trips and midgets. But although the component parts of a cult film can be identified, any attempt to set out to make a cult film is likely to end in failure. We agreed that cult movies were both ironic and sincere.

The panel were asked to present clips to illustrated our discussion. Jones chose a wildly camp extract from Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), the ill-advised 20th Century Fox studio film directed by the king of the cults, Russ Meyer. Mendik opted for the climax of Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) in which Leatherface performs a wild, nihilistic dance while an intended victim slowly loses her mind. Wise went for Mario Bava’s Bay of Blood aka Twitch of the Death Nerve (Ecologia del delitto, 1971), not one of the 100 Cult Films, but a giallo favourite by a key director and moreover a film with a juicy alternative title that features a highly innovative murder. After much dithering, I selected an unlikely double bill of Häxan (Benjamin Christensen, Sweden, 1922) and Café Flesh (Stephen Sayadian, USA, 1982).

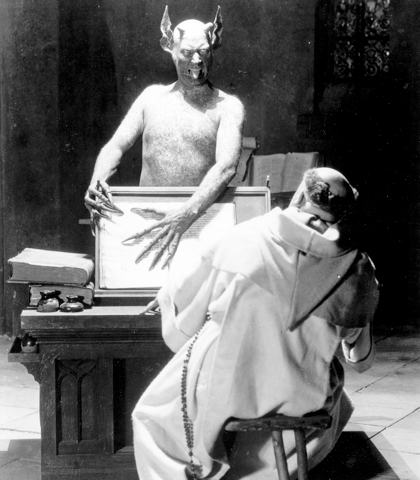

A quasi-documentary portrait of medieval devil worship, Häxan is a brilliant folly, an eye-wateringly expensive, overblown production that was so explicit and credible in its scenes of torture, nudity and ‘sexual perversion’ that it was practically unshowable, being banned or cut in many countries throughout the decades.

There were endless scenes I could have chosen, from the recreation of a Witches’ Sabbath to the Dreyer-esque trial of an accused elderly peasant, or the 20th-century hysteric in psychoanalysis, but ultimately I couldn’t resist the sequence in which the director himself pops up playing a horny devil to tempt a housewife from her conjugal bed.

I also chose to show not the tinted restoration, but the shorter, black and white 1968 release version with the narration by William S. Burroughs. This allowed me to discuss the influence of eccentric genius (and Bela Lugosi fanatic) Anthony Balch, who went from directing Kit Kat commercials to Towers Open Fire (1963), and was instrumental in London’s cutting-edge exhibition/distribution scene.

Café Flesh

Café Flesh was on my mind because it had recently shown in the Scala Forever season. I used to write about the film in my Film Studies essays, as a rich source of material with its themes of voyeurism and performance and a thundering post-apocalyptic AIDS allegory (although it was made in 1982, when the full horror of the virus had yet to reveal itself).

As creative director for Larry Flynt’s Hustler magazine, Sayadian’s movie remains the epitome of post-punk porno chic and features an electronic score by music producer Mitchell Froom (he of Crowded House albums, and ex Mr Suzanne Vega). I was pushed to find a clip that didn’t feature hardcore sex, but finally settled on the ‘skull in the cage’ speech by the film’s demented MC Max Melodramatic – the bastard offspring of Joel Grey and Henry Rollins.

Danny Peary said that cult movies are born in controversy and argument over their merits or quality, that they are “special films” (for ‘special people’! Or rather for the blessed few) that elicit a “fiery passion”. Despite the inclusion of blockbusters on the list, the panel were in agreement that the traditional definition of cult movies remains viable: these are films that are more heard about than seen.

The 1970s-80s remains the golden age of the cult movie, the moment when atmospheric big screen repertory cinemas or student film societies engaged audiences with a very wide range of films, while home video was just starting to take off and the limited number of films you could rent were particularly memorable, both because of their extreme content but also for the sheer impact on young minds of the arrival of the format in the home.

Cult films speak loudly to audiences’ imaginations – they deal in the uncanny, the spiritual and the surreal, and present an alternative that fulfils our desire to believe strongly in everything that our parents detested. What has changed is the issue of availability. The maturity of the DVD market and the accessibility of the internet give us ways of seeing everything, but small and privately. In this context, making sense of what we see becomes the real issue.

Welcome guests

Joseph Cedar’s Footnote

Geoff Andrew, 23 October

In terms of sheer fun, one of the most rewarding things about being involved in one way or another with the London Film Festival is always the opportunity it affords to meet up with filmmakers coming to the city from around the world. This year is no exception.

First up, flying in from Istanbul, there were Nuri Bilge Ceylan and Zeynep Özbatur, respectively writer-director and producer of Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, without doubt one of the monumental achievements of the cinematic year. Nick James has already written about the movie in rightly glowing terms and when the filmmakers and I returned for a Q&A at the end of a screening, most of the audience were clearly likewise impressed; why else would they stay on for more, at 11.15 or later, after a film lasting more than two and a half hours? Happily, Ceylan and his producer were in very eloquent form, so that even when we had to wrap up the Q&A just before midnight, hands were still raised for further questions.

Likewise articulate, after arriving by train from Brussels as part of a promotional tour taking in various European and North American cities, were Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, in a Q&A hosted by Nick as part of the Sight and Sound special screening of The Kid with a Bike, which back in May had shared the Grand Prix with Ceylan’s film in Cannes.

Where the Turkish movie is lengthy and slow (but never for one moment less than engrossing), the Belgian one is just 87 minutes long and quite amazingly pacy, deriving its enormous energy from its often frantic 11-year-old protagonist as he searches first for an absent father and then for a stolen bike. Heartbreakingly serious, the film is nevertheless notably sunnier (both literally and metaphorically) than the Dardennes’ previous work; their jocular responses in the Q&A may have surprised (and delighted) all those unfamiliar with their on-stage appearances, but the many laughs they elicited never concealed the fact that the brothers knew, in each and every scene of their film, precisely what they were doing and why.

The same goes for Terence Davies, in from the wilds of Essex for a session with yours truly in which he chose and discussed a number of clips from films which had influenced him in one way or another. Of course, most of those familiar only with the great man’s work may quite reasonably expect him to be a miserabilist through and through, but anyone who’s had the good fortune to catch any personal appearance by the adaptor-director of The Deep Blue Sea – the Festival’s closing night movie – will know Davies is a lively, engagingly irreverent and frequently hilarious interviewee. So it proved as he told the audience his various reasons for selecting excerpts from The Robe, Victim, Autumn Sonata, The Pajama Game, Merry Andrew and other titles; even this long-term Davies aficionado learned things new.

All the aforementioned filmmakers I’ve met a few times before, but I’m looking forward to a first encounter with Joseph Cedar, the writer-director of Footnote, a terrifically original, fresh-feeling movie that deservingly won the Best Screenplay prize in Cannes. (No mean feat when the two first prizes went to Malick, Ceylan and the Dardennes.)

I haven’t seen the earlier features by the New York-born Israeli filmmaker, but was very impressed by my two viewings to date of this astute, acerbic account of the love-hate relationship between a father and son caught up in ferocious professional rivalry in Jerusalem’s academic establishment. It’s hard to persuade others – I know from experience – that a film about arcane Talmudic scholarship can be funny, touching and exhilaratingly inventive, but do take my word; this film has yet to find a UK distributor, and these festival screenings may be your only chance to catch a real gem which, apart from anything else, manages to find a narrative form that is at once wonderfully literary and supremely cinematic. Never has a tricky meeting in a cramped room been depicted so skilfully.

Finally, and sadly, it turns out Paolo Sorrentino won’t be returning this year’s festival, but his fifth feature – This Must Be the Place – is something I highly recommend. If Italian cinema left its mark at last year’s LFF with Michelangelo Frammartino’s memorably unusual Le quattro volte, Sorrentino’s film is this year’s rich and strange equivalent. Michel Piccoli may make a particularly fine Pope for Nanni Moretti, but Sorrentino’s weird and wonderful fable does have the edge.

Rich and strange: The First Born

Thirza Wakefield, 22 October

Miles Mander’s 1928 silent film The First Born screened to a full house at the Queen Elizabeth Hall last Thursday night. BFI Head Curator Robin Baker opened with a fascinating and neophyte-friendly presentation of the film’s history and its painstaking repair by the archive team. Before-and-after footage described the tasks and techniques typical of the restoration process and peculiar to this project – memorably, the mid-scene disappearance of a housemaid in the BFI’s only owned copy of the film.

The presence of a live band (Janey Miller on oboe, Martin Pyne on percussion and Stephen Horne on piano, flute and accordion), installed far left of the screen, was almost as uncanny as the vaporising maid. But this anomaly takes no getting used to: it’s extraordinary how you forget that the music isn’t issuing from the picture and hasn’t always belonged to the film – a testament to the exceptional sensitivity and invention of Horne’s original score. The addition of a sleazy Gallic accordion to announce the libertine Nina de Landé was particularly amusing and, I wonder, a reference to Bioscope’s contemporary appraisal of the film as suited for “continental trade”.

The First Born, starring Mander himself and an ingénue Madeleine Carroll, is a violent and libidinous affair. The film begins with the separation of Sir Hugo Boycott and his wife on account of her failure to bear him a son, and what follows can only be described as an emotional disaster movie for the long-suffering Lady Madeleine. Mander’s paroxysmal physicality as the volatile philanderer is genuinely frightening and Carroll’s Madeleine is lovely, never sugary nor pious, having a brightness even as blow follows blow. There are moments in the film of such sensual provocation that they surprised (and embarrassed) the audience, and its indictment of Hugo’s deep-rooted misogyny is the more effective because directly and impartially represented.

The First Born was co-written by Alfred Hitchcock’s wife and long-term collaborator Alma Reville, and it’s clear the pair shared a gift for visual devices and, yes, suspense. The film’s playful imagery is reminiscent of Hitchcock’s own silent works and his later talkies – the dramatic use of a switchboard operator in Mander’s film is also to be seen in Hitchcock’s silent Easy Virtue, released the same year, and when the bird’s-eye circle of a dining table fades to a spinning record, Psycho comes to mind. And the film has all the timing and tension of a late Hitchcock picture.

Indeed, The First Born impresses not only within the silent tradition but out of its time. The restoration of the film’s original tinting – in amber, straw, lavender and pink – enhances its natural atmosphere, and the narrative titles are so distinctly voiced as to make you forget, once again, that this is a silent film. Intelligent and gripping, intimate and disturbing, The First Born is an accomplished, deserving example of early cinema.

« Week one