Festival report

On the road to Telluride

Andrei Tarkovsky, somewhere in Utah

Nick James on bringing home Sight & Sound’s ‘Special Medallion’ from the Telluride Film Festival, “given to a hero of cinema that preserves, honors and presents great movies”

Telluride Film Festival

Colorado, USA

September 2011

I’m floating in a smooth part of the Colorado River, hanging onto the back of a raft being rowed by Rachel, our teenage guide. I’m gazing at two huge dark red, cathedral-like mesas on the skyline. “Y’see that one on the right there,” Rachel says, “that’s the one where MTV shot John Bon Jovi. I guess a helicopter dropped him on. Can’t imagine him climbing up there. I don’t know about his music, but my aunt’s crazy for him. Does anyone know a Jovi song?”

Silence falls; the same hush that greeted most of Rachel’s jokes. It lets in the gentle lapping of the water. Part of our guide’s charm is that she likes it when her bon mots fall as flat as the river. After a few tense seconds I break. “Um, ‘Livin’ on a Prayer’,” I say. “Oh yeah,” says Andy, the burger-flipping snowboarder riding bull at the bow. He starts singing: “Whoa-oh, we’re half way there, Whoa-oh, livin’ on a prayer…” Then he stops.

All is quiet again, and I feel grateful – for the lull, the cooling water in the baking sun, my wayfarers and even my floppy Australian tie-on hat with its holes. And then my friend Tom Luddy, a founder of the Telluride Film Festival, who’s floating on the other side, speaks up. “Nick,” he says. “When I brought Tarkovsky here he was already dying of cancer. I tried to tell him about how the water erosion had sculpted what you can see all around you. He wouldn’t hear of it. ‘No, no,’ he said – ‘God made this.’”

The legendary Russian knew ‘God’s country’ when he saw it. I’m being shown around the same sites of Utah by Tom, along with his wife Monique and friends. My meagre bank of superlatives has already run dry – “My cup overfloweth” is all I can say, repeatedly. The trip is a pre-festival holiday, organised because Telluride is honouring Sight & Sound this year and I wanted to take advantage of Tom’s enthusiasm for the landscape. Werner Herzog has also drifted down this river with him, no doubt with monkeys on the raft.

Park Avenue in Arches National Park

Our four-day caravan from Salt Lake City to Telluride takes in Arches National Park, Dead Horse Point, Goosenecks, the Valley of the Gods and that location forever owned by John Ford’s westerns (and the Navajo), Monument Valley. Each vista is a totally different variety of corker. At one point, on a trip when Tom isn’t with us, we pass a yellow train with the word ‘Herzog’ on the front. It seems like an omen – but then everything seems like an omen in this landscape. As I tell Tom when we’re back on the road with him, “You’re certainly giving your festival a hard act to follow.”

We approach Monument Valley in a thunderstorm. To see John Ford’s epic set shrouded in black and grey with lightning forking left and right makes a tumultuous conclusion for our trip but it’s not over yet. We think the rain has killed our chance to ride horses, and this non rider is quietly relieved. However, the weather clears in 20 minutes and by then there’s not a drop of water on the ground. The red earth of the valley floor has sucked it all up. And soon I’m riding a Navajo pony too tired to throw me. Half way there in John Ford’s pigment playground.

Backstory

Tom Luddy broke the good news to me in Berlin back in February. I was to be invited to Telluride to receive their ‘Special Medallion’ on behalf of Sight & Sound. During the San Francisco Film Festival in April he arranged for me to meet the other members of the Telluride triumvirate, Julie Huntsinger and Gary Meyer. They were all super-welcoming hosts but there was an immediate understanding that I would be required to present something special that the cognoscenti who attend Telluride might not have seen. One film to represent what S&S stands for. But what film?

I felt intimidated. I knew it had to be British because, although the S&S editorial team pursues our strapline ‘The International Film Magazine’ to the full, we like to keep a special eye on British cinema and nurture hopes that it can at times be among the best in the world. And as far as I’m concerned, any British film representing S&S has to represent British formal and aesthetic experiment and a romantic sense of the British landscape. In other words it had to be as close as we could get to, say, an undiscovered Powell & Pressburger film. An impossible task? I thought so until I got back from California and asked my colleagues. Penda’s Fen was the immediate suggestion from Kieron Corless and James Bell.

Penda’s Fen is a remarkable little-seen television drama, a patchwork of politico-religious-philosophical musings on the state and the landscape of England that’s all the better for constantly reaching beyond its means. Made for the BBC’s ‘Play for Today’ strand in 1974, it brought together playwright David Rudkin and director Alan Clarke, a series regular.

It’s a true meeting of different forms of intelligence. Rudkin’s writing and interests are of a kind that’s now mostly banished from the UK airwaves, very concerned with the visionary poetry of the English landscape and the meaning and origin of place names.

Clarke was already a veteran director of social realist drama, though he had not yet made his breakthrough into notoriety and acknowledged filmmaking excellence. That would come with his banned production of Scum (1977) and continue with the film version of Scum (1978), then his astonishing run of groundbreaking films that includes Made in Britain (1982), Contact (1984), Christine (1987), The Road (1987), Rita, Sue and Bob Too (1987), Elephant (1989) and The Firm (1989).

The drama traces the emergence of Stephen, a teenage schoolboy, from the chrysalis of loyalty to church and state. A vicar’s son and the school organ player, he combines dedication to conservative and militarist causes with a deep fascination with the music of Sir Edward Elgar, particularly the oratorio The Dream of Gerontius, taken from Cardinal Newman’s poem about a dying man’s soul and its progress to heaven. However, a series of strange encounters combines with his sexual fascination with the brawny lad who delivers the milk to the vicarage to create an internal rebellion that flowers into visions.

Penda’s Fen

It is said that working on Penda’s Fen gave Alan Clarke the daring to experiment with form in his later work, but there’s no getting round the tentative feeling in his direction of Rudkin’s screenplay. There’s a clumsiness to the editing and to the didactic elements of the play, but Clarke’s willingness to employ blatantly fake forms of special effects to realise Rudkin’s visions of angels and demons and figures like Sir Edward Elgar and Penda, the last pagan king of England, gives stark force to the visuals.

Penda’s Fen covers huge areas of key English themes and concerns with tremendous concision, and it plugs directly into the new interest in what we at S&S like to refer to (pace Greil Marcus) as “the old weird Britain” (see S&S August 2010).

When I told Tom Luddy we wanted to present Penda’s Fen he got excited. Not only did he know the film, but he’d also wanted to screen it when Telluride had done an Alan Clarke tribute in 1994. There were problems getting the rights cleared for the screening, but with help of certain heavyweight names and tremendous goodwill on the part of the rights holders, Telluride got the greenlight. So I arrived in that San Juan mountain village in a state of semi-ecstatic gaga with the prospect of a weird film to show and feeling very well disposed towards the festival.

Etiquette

I didn’t lose that feeling. For one thing, Telluride is in a gorgeous mountain setting; for another, as I quickly discovered, it’s the Bentley of film festivals: discreet and impeccably engineered to make you feel comfortable all the time. The programme is a fulsome and eclectic three-day infusion of cinema at its best, and ensures you’re left wanting more. You wander around in the mostly pleasant weather amongst the friendliest crowds. Everyone seems curious without being rude or (with one or two exceptions) intrusive. It’s a nice vibe, as they say.

Among the fine new films showing that I’d already seen were Aki Kaurismaki’s Le Havre, Martin Scorsese’s George Harrison documentary Living in the Material World, Bela Tarr’s The Turin Horse, Michel Hazanavicius’s The Artist, Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation, Joseph Cedar’s Footnote, Wim Wenders’s Pina, Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin and the Dardennes’ The Kid with a Bike. Even with those items off my schedule I could not see everything I’d have liked to.

One of Telluride’s virtues is that it keeps all the press away bar a few specialists, allowing actors and filmmakers who come to relax and enjoy themselves without much hassle. I reveled in this, of course, but wondered what the etiquette might be if, for instance, you were to banter with someone famous. Should you write about it? The answer is obvious: you’re a guest, so you probably should ask permission.

It was remarkable to see, for instance, George Clooney standing chatting in the audience before the premiere of Alexander Payne’s The Descendants, in which he stars as Harry King, a Hawaiian neglectful father whose driven, sporty wife is suddenly critically injured in a boating accident, leaving him in charge of two daughters close to coming off the rails.

The Descendants is Payne’s long-awaited follow-up to his genial midlife-men-on-the-skids comedy Sideways. King, as Clooney has it, is a bit of a “schlub”. As trustee and partial heir to a large and inviting parcel of untouched real estate on Hawaii, he’s been absorbed in selling it off to the right bidder, thereby satisfying all his ne’er-do-well cousins. In the meantime Alexandra (Shailene Woodley), his teenage daughter, has been parceled off to a school for reprobates, and his younger daughter is also beginning to act up. Harry faces a double dilemma when it’s made clear his wife won’t wake from her coma, and he discovers she’s been having an affair.

The Descendants

No other writer-director is so good as Payne is at making you feel anguish while you laugh. It’s a strangely piquant state of mind that suits the film and the lightheadedness that comes from being at high altitude (Telluride is at nearly 9,000 feet). The Descendants is one of those rare mainstream films where you can feel the elegance of the craftsmanship almost without noticing it and it showcases one of Clooney’s most nuanced performances. In an all-round high-quality ensemble, Woodley is also particularly good, especially in the bravura scene in which she experiences extreme grief underwater.

With only The Descendants and a distinguished couple of hours of Mark Cousins’s The Story of Film under my belt – the whole 15 hours was playing in a loop in a storefront down the street – it was already time for me to introduce Penda’s Fen.

The Telluride ‘Special Medallion’ is for “a hero of cinema that preserves, honors and presents great movies.” Tom Luddy presented me the medallion – David Thomson was meant to, but was too unwell to travel.

I was very conscious that the award was the magazine’s, not mine, somewhat babbled my introduction and maybe didn’t quite prepare the Sheridan Opera House audience for how strange an experience Penda’s Fen is. Nonetheless it was pretty well received – although the full range of reactions shaded from opera impresario Peter Sellars’s fulsome thanks for being able to see it, and suggestion that the film indicated the possibility of a notional British Tarkovsky, to Alexander Payne’s shrugging and saying it seemed to him like a student film.

Sexual healing

Each year Telluride awards three tribute medallions. This year they went to Clooney, Tilda Swinton and the newly rediscovered French director Pierre Etaix. I was only present for Clooney’s special tribute – a choice clip reel followed by an interview with critic Scott Foundas. The actor is a smooth master of such occasions, shifting in and out of gears between serious comment and laconic humour like he’s on an endless shy victory lap. He’s thoughtful, sincere and funny by turns – I enjoyed his stories about chauffeuring his hard-drinking aunt, vocalist Rosemary Clooney, to and from gigs, and becoming way too acquainted at a young age with elderly female anatomy. These stories had a point, in that Clooney said he was very conscious of the way the Beatles and the British invasion had finished his aunt’s major career in an instant and that he knew that could happen to him at any time.

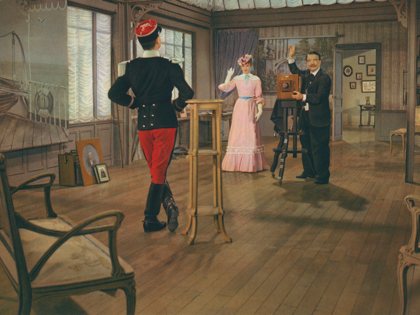

A lobby card for Les Grandes Manoeuvres

The rest of my festival mostly followed sexual themes, beginning with a delightfully wistful late René Clair film, Les Grandes Manoeuvres (Summer Manoeuvres, 1955). It’s about a pre-WWI garrison town cavalryman cum seducer betting he can bed a new arrival from Paris by a certain date, only to find she’s heard it all before and is already embroiled with a local entrepreneur. As they play the game of ballroom and boudoir bluff and rebuff, each falls for the other but neither trusts what the other says. Intricately constructed but apparently effortless, the story and mise en scène unfold with all the room and pinpoint timing that good acting needs. Wipe cuts add to the sweeping sense of insouciance masking so much heartache.

That was part of a small programme put together by Brazillian musician-singer-writer Caetano Veloso, which also included Glauber Rocha’s Black God, White Devil and Billy Wilder’s The Apartment. Veloso’s songs have enlivened the films of Pedro Almodóvar and Wong Kar-Wai.

One of the most satisfying moments of the festival came during Peter Sellars’s interview with Veloso in the Elks Park public space. The singer was most eloquent about the connections between his Tropicalia music movement and cinema novo (there’s even a song called ‘Cinema Novo’ on his Tropicalia 2 album) – but we could all see the guitar case on stage, so it wasn’t long before audience members were entreating him to sing. Veloso performed four of his delicately soaring songs, the standout of which was a heart-soothing Cucurrucucú Paloma.

I’m no silent-cinema expert, but I was not so convinced by archivist Paolo Cherchi Usai’s claims for his presentation of Karl-Heinz Martin’s 1920 film From Morning to Midnight. On the evidence of the beautifully sharp projection copy, his claim that this expressionist film is “a far superior work in purely cinematic terms” to Weine’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari does not stand up. Though the story of a bank clerk who steals and fritters a fortune is communicated clearly, and was enhanced by an exciting score performed live by the Alloy orchestra, I found the film amateurish in feel – especially the repeat motif of every attractive woman becoming a death’s head – and the mise en scène did not seem anything like so inventive as Weine’s. Perhaps I need to take another look at The Cabinet to compare.

The standout film of the festival for me was Steve McQueen’s chilly tale of sexual obsession Shame, about a corporate guy with a chic, stripped-bare New York apartment suffering from some kind of sex addiction that leads him to constantly masturbate, use prostitutes and have a laptop crammed with porn. His routine is disrupted when his sister Sissy (Carey Mulligan) turns up unannounced at his apartment. She’s a club singer whose presence clearly disturbs him, especially when she sleeps with his boss.

Sissy prompts an amazing performance from Mulligan, especially coming after her disappointing turn in Drive. She’s never less than convincing as a New York club habitué with unfinished brother business. McQueen is very good at creating scenes that allow the actors time to really show their chops without showing off. It’s a very downbeat, tragic study of human attraction and was the first of two films starring Michael Fassbender that dominated the end of the festival for me. Fassbender himself is brilliant here, and looks like a genetic mixture of Ewan McGregor and Daniel Day Lewis with flashes of Robert De Niro – no wonder he gets cast in nearly all the promising projects.

I don’t want to say too much about Fred Wiseman’s new documentary Crazy Horse, because I didn’t last the full course and I’m told the ending sequence is superb. The documentarian goes backstage and front at the famous Parisian nude cabaret, and discovers a world of high pressure, high standards of performance and ridiculous levels of pretension from the creative director, who comes on like he’s Jean-Luc Godard. On one level, it makes a perfect follow-up to Wiseman’s doc about the Paris Opera Ballet, especially since several of the girls employed at the Crazy Horse have ballet training, but for me there could be no greater contrast in their backstage worlds. This world, when it’s not titivating, is extremely dull – practice is technical, synthetic and charmless.

My second and final piece of duty at the festival was to interview writer-director Christopher Hampton, partly about A Dangerous Method, David Cronenberg’s film of Hampton’s play The Talking Cure. The film and play are derived from the papers of Sabina Spielrein (excellently played by Keira Knightley), who arrives full of uncontrollable tics as a patient for Carl Jung (Fassbender) and ends up as a psychoanalyst herself.

Essentially a love-respect triangle between Freud the strict theorist (ably manifested by Viggo Mortensen), Jung the experimental practitioner, and Spielrein – the test case who becomes a moral impediment between the great men, losing Jung his heir-apparent status – the film is a clean, scientific machine in its exposure of the cases and relations. I found it compelling and fascinating and was delighted when Hampton went along with the game of treating our interview a little bit like psychoanalysis. But more of that, perhaps, when Sight & Sound features the film.

It was, of course, a blast to wander around with the medallion on, and it took some time for me to come down from the heights, both literally and metaphorically. I hope I’ll be back.

See also

Darks nights of the soul: Jonathan Romney reviews Shame from the Venice Film Festival (September 2011)

Walking on air: Mark Cousins goes giddy for old films by Stanton Kaye and Mario Camerini, the latest from Harutyun Khachatryan, and Claudia Cardinale at Telluride (September 2010)

Beyond the horizon: Mark Cousins on the New Crowned Hope commission of films from Asia, Africa and Latin America (July 2007)

New boots and rants: Jon Savage on This is England (May 2007)

Red, white and brew: Mark Salisbury on Alexander Payne’s Sideways (February 2005)

About Schmidt reviewed by Xan Brooks (January 2003)