Primary navigation

An unclassifiable hybrid of documentary and fiction, Jia Zhangke’s ‘24 City’ finds a telling microcosm of the transformation of China in the story of a factory relocated to make way for a shopping mall. By Tony Rayns

In China these days, ‘change’ is not a political slogan but an everyday fact of life. Professional China-watchers are always saying that nothing ever really changes in China, and that may well be true, but it’s also true that virtually nobody in China lives the same life today that they did even ten years ago. People not only have the mod cons and fashions that were previously out of reach but also think differently, behave differently, relate to each other differently and have different aspirations. The sheer pace of social change, especially in China’s cities, can scarcely be computed by foreigners who haven’t witnessed it at first hand. Jia Zhangke is unrivalled as the poet of these changes.

24 City (Ershisi cheng ji), an unclassifiable hybrid of fiction and documentary, consolidates Jia’s shift from a Shanxi-centric view of China’s changes to a broader view of everything the country has been through since Mao’s communists came to power in 1949. Shanxi is Jia’s native province; his first three features were set there, and the fourth (The World/Shijie, 2004, soon to get a belated release here on Blu-Ray) and fifth (Still Life/San Xia Hao Ren, 2006) dealt with characters from Shanxi in other parts of China. But Shanxi doesn’t even get a namecheck here.

This film is set in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, some 300 miles west of Still Life’s Fengjie, and it ostensibly documents the removal of a large factory from the centre of the city to an industrial development zone on its outskirts. The prime site has been sold to a developer who is demolishing most of the old buildings and replacing them with a vast residential, business and shopping complex which has been given the name ‘24 City’, derived from a dodgy translation of an ancient poem about Chengdu. Jia provides images – often quite surreal – of the abandoned buildings, the movement of equipment to the new site, the demolition and new construction, even the architectural models, but the logistics of urban redevelopment are the least of his interests. As always, he focuses on the impact of changes on individual lives: most of the running time is given to eight interviews with local people, six of them past or present workers in the factory and two of them adult children of factory workers.

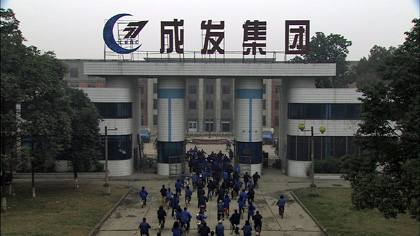

The particular thing about this factory (and this is undoubtedly what persuaded Jia to make the film) is that it used to be a state secret. Its history is sketched succinctly in the second interview: the retired head of security Guan Fengjiu, clearly a stolid servant of the Party, recounts how he first worked in Factory 111 in north-east China, repairing the engines of MIG-15 fighter jets used by the Chinese army in the Korean War, and moved to Chengdu in 1958 (along with 4000 other workers) to carry on “the fight against US imperialism” in the newly built Factory 420. He doesn’t say so, but the move was actually occasioned by the break with the Soviet Union in 1956; Mao Zedong decreed that military-support factories in the heavy-industry belt of the north-east were too vulnerable to Soviet attack, and so needed to be moved to secure inland areas – such as Chengdu in the remote mid-west, shielded by mountain ranges. Subsequent interviews fill in more of the details: Factory 420 was first given the name ‘Xindu Machinery’ to disguise its ‘sensitive’ work, and then became the ‘Chengfa Group’ in the early 1980s when it diversified into manufacturing white goods such as fridges and washing machines to boost its income. Again, no interviewee spells it out, but the latter change was prompted by Deng Xiaoping’s order that state enterprises should seek to make profits in the post-Mao era; an even more decisive factor was the trouncing of the Chinese army in the 1979 border clashes with Vietnam, which forced army chiefs to rethink their arms-manufacturing priorities as well as their military strategies.

The reason the more embarrassing episodes in this history are not spelt out in the interviews is that nobody in present-day China would be stupid enough to voice them; despite the social changes, China remains a one-party authoritarian state. The film is in any case nothing like a lesson in political history. But even with its glossing-over of political mistakes and tactical failures, the factory’s backstory provides an essential context for the film’s poignant tales of blighted lives, dashed hopes and forlorn retirements. Factory 420 serves, in fact, as a microcosm of the communist state.

From its establishment in 1958 as a prosperous world apart from the economic hardships faced by ordinary residents of Chengdu (the factory provided its workers with good salaries, accommodation, sports and leisure facilities and schooling for their kids, and there was no fraternisation with the locals), through its struggle to adapt and modernise in the go-getting 1980s to its ignominious shut-down in 2008 to make way for yet another hotel, ‘luxury’ apartment complex and shopping mall, the factory has faithfully mirrored every phase of the Party’s central planning for the country. Jia is too smart to dwell on the ins and outs of policy reversals; instead, he counts the human cost of submission to Party orders.

He also constructs a social history which, like the one he explored in Platform (Zhantai, 2000), is deeply rooted in pop culture. This is presumably the main reason he cast two well-known veteran actresses as retired factory workers: both Lü Liping and Joan Chen bring to their roles long personal histories which resonate in fascinating ways with the (scripted) stories they tell. Best known here for The Blue Kite, Lü has often played victims – which makes her sketch of the elderly, infirm widow Hao Dali surprisingly barbed; Hao has devoted her entire life to Party service, to the extreme extent of abandoning a search for her kidnapped child to take up her work assignment, and is now helplessly baffled by the new materialism. Meanwhile Joan Chen, who has done everything from starring in Twin Peaks to directing a Richard Gere movie, takes a role which looks back to her real-life origins as the Shanghai ingénue who became the nation’s sweetheart with her debut in Little Flower (Xiao Hua, 1979, directed by Zhang Zheng). She plays Gu Minhua, who arrived in Factory 420 at the height of Little Flower’s popularity and was endlessly compared with its heroine, but then faced a lifetime of romantic disappointments because she put her image and career ahead of personal happiness; Gu’s story is obviously not Chen’s own, but it offers a sour commentary on the likely fate of those caught up in the romantic delusions of the late 1970s. There are two other professional actors in the film’s cast of interviewees, both chosen to embody a distaste for factory work and an eager capitulation to China’s glossy new ‘values’: Chen Jianbin as the TV newscaster Zhao Gang, and Jia’s muse Zhao Tao as a woman who visits Hong Kong once a fortnight to shop for the nouveau riche women of Chengdu.

24 City belies its documentary origins with overtly poetic film language: the film is an elegiac visual symphony of carefully framed compositions, trompe l’oeil camera movements, posed portraits, internal rhymes and mysterious vignettes. It’s also as much a lexicon of body language as anything Andy Warhol achieved in his early portrait reels. But as befits a film containing so much spoken language, there’s also verbal poetry – apposite quotations from Yeats and various Chinese poets – periodically used as captions over the images. These no doubt owe their appearance to Jia’s co-writer, the woman poet Zhai Yongming; they help edge the film into larger historical and philosophical perspectives. This profoundly Chinese movie refuses to be limited by its Chineseness. Jia’s working title for it was a Lumière Brothers reference: Leaving the Factory.

Jia Zhangke discusses blending fact and fiction on page 49 of the May 2010 issue of ‘Sight & Sound’

Platform: one of Sight & Sound’s 30 key films of the 2000s (February 2010)

Still Life reviewed by Tony Rayns (February 2008)

Still Life: three critics’ choices in Sight & Sound’s Films of 2006 (February 2010)

Xiao Wu reviewed by Tony Rayns (March 2000)