Primary navigation

UK 1966

Reviewed by Paul Tickell

Paul Tickell on a decade of counterculture and class change – and the Karel Reisz movie that defined it

Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment

Karel Reisz; UK 1966; Optimum / Region 2; Certificate PG; 93 minutes; Aspect Ratio 1.66:1

Nineteen sixty-six was a cusp year: the Beatles’ songwriting was becoming marked with studio experiment, and LSD, not just cannabis, was becoming the order of the day – and night. There was also an urgent sense of social transformation, of some coming upheaval great enough to blow away the British class system. In short, revolution was in the air and pop culture was restyling itself as the counterculture. It’s this moment – to a Johnny Dankworth score rather than the sound of incipient psychedelia – that Karel Reisz’s Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment captures so accurately and so comically, though its humour is tinged with melancholy.

Reisz had already shown himself adept at picking up on the signs of the times. In Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), factory worker Arthur Seaton sticks two fingers up to authority and takes a rollercoaster ride into the kind of hedonism that would come to define the Swinging 60s. Arthur is derailed, of course: the British class system knows how to deal with upstarts.

But by the time of Morgan, the rebel’s yell was music to the ears of the Establishment: it could be packaged and sold – rather like the paintings of the film’s antihero Morgan Delt (David Warner). Wearing his alienation and working-class origins on his sleeve, Morgan’s been doing rather nicely out of a fashionable gallery, whose upper-class owner Napier (Robert Stephens) barely bats an eyelid when Morgan turns up with a pistol. For Napier, such menace is all part of Morgan’s charm as a ‘with it’ commodity who can be bought and sold; it’s a ‘repressive tolerance’ that goads Morgan all the more, especially as Napier is having an affair with his wife, the monied Leonie (Vanessa Redgrave). Much of the film’s episodic plot revolves around Morgan seeking to regain entrance to the Kensington home from which he’s been ejected, and his desire to reassert his conjugal rights.

Morgan started life as a 1962 BBC television drama written by David Mercer, who is as much the film’s auteur as Reisz. Mercer is a writer adept at laying bare – even in the midst of such zany farce – the psychic wounds and even violence at the heart of bourgeois marriage (his 1968 TV drama Let’s Murder Vivaldi was another exploration of this theme). The knockabout, absurdist humour of Morgan’s antics occasionally sours; there are rape ‘jokes’ (as in the previous year’s The Knack) and a relish in uncomfortable physical detail such as the smell of Napier’s hair-cream around the house.

Disturbingly, Morgan seems to rather enjoy licking his wounds. The masochism is there in his politics too. He pines for Leon Trotsky not because of his philosophy of Permanent Revolution (which so chimed with the 1960s, from Maoist Red Guards in China to student radicals in Europe and the US) but because he suffered exile and death in Mexico. Morgan lives in his own little Mexico – a car parked outside the marital home complete with a poster of his hero. But Trotsky as romanticised by Morgan is not the only revolutionary figure to feature. During a visit to Marx’s tomb in Highgate, the film has a scabrously funny take on the generation gap, as Morgan’s mother reminds him that his dead father would be very disappointed at how he’s turned out – a narcissist who’s prey to lunatic nonsense instead of a young revolutionary shooting the Royal Family and putting public schoolboys in chain gangs.

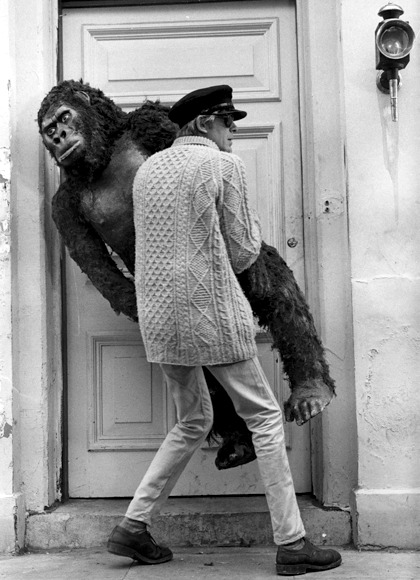

Narcissist or not, Morgan does actually do things – even if, rather than changing the world, it’s kidnapping Leonie and then, after a spell in prison, crashing her wedding to Napier. Starting out as a hipster holy fool in dark glasses, by the end Morgan dresses in a gorilla suit – a last gesture before the straitjacket…

The film concludes in full hallucinatory mode, with montages from King Kong and the zoological documentaries that have featured throughout the film. These inserts are highly subjective because they represent Morgan’s dreams and fantasies and a point of view that screams: “It’s the world that’s insane, not me; and if I am then the world made me so.” It’s the point of view of a cartoon Marxist gorilla/guerrilla, but one steeped in the ‘anti-psychiatry’ of R.D. Laing and David Cooper, whose work Mercer was to draw on in a far more realist way in the 1967 TV drama In Two Minds, which later became the Ken Loach film Family Life (1971).

On one level, Morgan can seem very dated; on another, it’s of its time in an exhilarating way – a bit like one of its closing sequences, in which Morgan rides his motorbike through the streets of an eerie, somnambulist London: uneasy rider meets William Blake.

It’s testimony to Reisz and Mercer that their experimentalism resides not just on the technical level (the film uses freeze-framing and speeded-up action) but also on the philosophic plane: they are fearless about ideas and the comedy to be had from them. There’s nothing tentative about Morgan, from the clarity of its black-and-white image and the energy of the editing to the powerfully direct acting of the whole cast. It’s unheard of to find such confidence or this degree of the fantastical in today’s British film comedy, where arch plots often revolve around social and romantic embarrassment, and where it’s all about the makers’ very repressed way of talking, or rather not talking, about class: don’t mention the (class) war.

Morgan has no such inhibitions and lets it all hang out. Morgan the character indulges in a provocative early form of street theatre, his prankster’s tools – his agitprops as it were – the analyst’s couch and confessional as much as the soapbox. No wonder the film became a favourite of the young Malcolm McLaren, who even took to living in a car for a while in tribute.

Lost and forgotten: British cinema of the 70s: Mark Sinker discovers a selection of the era’s ‘forgotten’ films (July 2010)

Betsy Blair, 1923-2009 (March 2010)

New boots and rants: Jon Savage on Shane Meadows’ This is England (May 2007)

Sound and the fury: David Thomson on Terence Davies’ autobiographical The Long Day Closes (April 2007)

Karel Reisz’s top ten films (December 2002)

Ken Loach’s ‘not’ top ten (December 2002)

Soup dreams: Lorenza Mazzetti tells Bryony Dixon and Christophe Dupin about their Soho cafe origins of the Free Cinema movement (March 2001)

Free Cinema programmes (March 2001)