Primary navigation

Reviewed by Jonathan Romney

Miklós Jancsó’s ‘musicals’ use songs, crowds and landscape to express social struggle, writes Jonathan Romney

Red Psalm

Miklós Jancsó; Hungary 1971; Second Run / Region 2 DVD; 82 minutes; Aspect Ratio 1.85:1/16.9 anamorphic; Features: Jancsó documentary Message of Stones – Hegyalja (1994), booklet

The Miklós Jancsó Collection

My Way Home / The Round-Up (pictured above)

/ The Red and the White

Hungary 1964/65/67; Second Run / Region 2 DVD; Certificate 15; 264 minutes total; Aspect Ratio 1.85:1 anamorphic; Features: short films, director interview, essays

If I think of socialist musicals, two immediately come to mind: Miklós Jancsó’s Red Psalm and Jacques Demy’s Une chambre en ville. It might seem facetious to compare these two directors, since Jancsó is generally associated with 1960s/1970s cinema at its most serious, while Demy is often considered the epitome of all that is frothy and Hollywoodian in France. This is, at the very least, to underrate the seriousness and toughness of Demy’s 1982 film, about a strike in Nantes – but my point is that both filmmakers are distinguished by their use of music as a primary element and by their innovative use of crowds and landscapes. Both organise huge numbers of people – actors, singers, dancers – in extensive open-air spaces which they use as quasi-theatrical stages. Demy uses real towns, as in Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (an extraordinary case of urban space invaded by a cinema event), while Jancsó uses the country, whether it’s the more restricted fields of Red Psalm or the vast expanses of The Red and the White (1967), in which the reversals of war are enacted with masses of players, human and animal, using hills and valleys as a giant chessboard.

It might seem flippant to call Red Psalm a musical, so let’s describe it more specifically as a Brechtian lesson in history and politics, using folk songs and other sound materials to offer a polyphonic demonstration of the trials of social unrest. With its 1,500 extras, Red Psalm is, if you prefer, a pageant, a ritualistic enactment of revolutionary events – not specific but archetypal ones, though the action is understood to refer generally to rural uprisings that took place in Hungary between 1890 and 1910. Red Psalm is the accepted international title, although the Hungarian title (Még kér a nép) means The People Still Demand, a quotation from the poet-revolutionary Sándor Petofi. Either title works. The original refers to the persistence of popular demands despite all obstacles: the film culminates with an insurgent crowd gunned down by troops, after a militant announces that the fruit of popular struggle will come not yet, but later. But Red Psalm works too, declaring that the film is a visual cantata to social change.

Raymond Durgnat saw Red Psalm as belonging to what he called the “intellectual-symbolic” cinema of the 1960s, a cinema that today seems like a lost language, an aborted possibility. Durgnat defines this cinema as “films which pursue a line of argument, or thought, or description”, citing such diverse titles as Les Carabiniers (1963), Culloden (1964) and Oh! What a Lovely War (1969). Jancsó certainly belongs to a school of symbolic cinema; in its use of motifs from political, religious and folk iconography (the red imagery alone includes streamers, flowers, rosettes, leaves, a bloody river), Red Psalm is perhaps closest to Parajanov. Jancsó’s use of quasi-ritual movements performed in landscapes and shot in daringly long takes is close too to Theo Angelopoulos (he was also, for this very reason, a massive influence on Béla Tarr). It’s impossible moreover to think of Red Psalm outside the context of post-Brechtian 1960s/1970s theatre – including John Arden, diverse American happenings and Robert Wilson’s vast outdoor stagings.

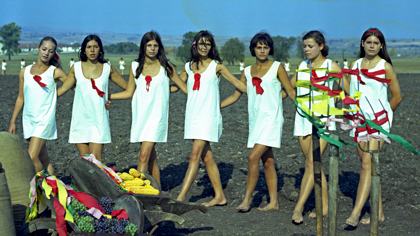

Red Psalm

Red Psalm offers a dizzying vortex of action and information. Within the flow of the work, abrupt breaks and shifts occur. Songs in a variety of folk modes start, only to break off or be interrupted by other music, or by concrete sound effects (bells, cracking whips). Among the masses on screen, several groups emerge: soldiers, landowners and their agents, farmworkers, three young women who periodically strip off to resemble the Graces. Among them, a few individuals make a mark, but only a handful are given names. Events flare up with startling brutality: a maypole dance becomes a massacre, a church is burned down with its priest inside. Within the swirl of choreographed action, the camera periodically stops to pick out details: faces and bodies in the closing survey of the slaughtered; close-ups of hands, a white dove; a still life of country food. Jancsó planned his choreography and camera movements on location, resulting in a restless immediacy, the camera caught up in the whirl as inquiring observer and as participant. Similarly, Jancsó offers us a mass of contrasting, contradictory arguments, texts and songs – revolutionary chants, a landowner expounding the laws of supply and demand, a letter from Friedrich Engels.

Red Psalm represents a form of cinema that seems unsettlingly, excitingly alien to us today. But if one thing marks it as a film of its period, it is – more than the politics – the use of female nudity, for which Jancsó was attacked for cynicism by the communist authorities. Nothing in Red Psalm seems so much of its era as its three naked women representing the unabashed spirit of the people: it now seems transparently a modish 1960s/1970s instance of sex selling politics – cheesecake in service of the revolution.

This DVD release sees the intensity of the film’s colours magnificently restored. Three other titles – My Way Home (1964), The Round-Up (1965) and The Red and the White (1967) – are being re-released by Second Run in a box-set to celebrate Jancsó’s 90th birthday. It would be fascinating to investigate his later films, to discover what happened after his fall from international favour in the 1970s – for example, his recent spate of domestically popular comedies. Even to rediscover these four films, though, is like seeing the turrets of a long-lost city emerge from underwater.

Out of the shadows: Ian Christie celebrates folk magician Sergei Parajanov (March 2010)

Pied Piper reviewed by Tim Lucas (DVD, July 2008)

Trilogy: The Weeping Meadow reviewed by Nick Roddick (January 2005)

The Werckmeister Harmonies reviewed by Jonathan Romney (April 2003)