First-look reviews

London Film Festival 2011:

New filmmakers, new voices?

Our critics cast a glance at the films shortlisted for the LFF’s Sutherland Trophy, given to the maker of the most “original and imaginative” first feature screened in the festival

Las Acacias

Pablo Giorgelli

Argentina-Spain 2011

With Germán de Silva, Hebe Duarte, Nayra Calle Mamani

Argentine documentarist Pablo Giorgelli’s first feature, winner of the Camera d’Or at Cannes this year, is a slow-burning beauty. Lorry driver Ruben is tasked by his boss with taking a Guarani woman, Jacinta, and her baby across the border from Panama to Buenos Aires to stay with her cousins (and work illegally, it’s implied). At first Ruben seems like one of Lisandro Alonso’s solo men, withdrawn and at odds with the world, resentful at the baby’s presence. Gradually, though, a subtle shift takes place.

There are several wondrous elements to Las Acacias. One is the cinematography, not least its intricate negotiation of the most confined space imaginable, and its mapping of Ruben and Jacinta’s growing intimacy – two of life’s stoics sussing each other out slowly, more often than not wordlessly. We glimpse into their pasts, but nothing more; hints at dark stuff – the scar on his back, the baby having no father. The performances, by non-professionals, are perfectly pitched, astonishing. But more than that, both actors are warm, real, lived-in presences, people you want to spend time with and get to know.

It’s also another glimpse into Argentine life outside the capital, the roadside stops and trucker life grounding the film in a social reality. I’ve heard this film described as slight, but I’d beg to differ. So much is understated or unspoken – the racial politics, the poverty, isolation – but it’s all there up on the screen. Ultimately, too, there’s the possibility of love, two (or even three) lives transforming – what could be bigger than that?

Kieron Corless

Pablo Giorgelli was named the winner of this year’s Sutherland Trophy

Corpo Celeste

Alice Rohrwacher

Italy-Switzerland-France 2011

With Yle Vianello, Salvatore Cantalupo, Pasqualina Scuncia, Anita Caprioli

Rohrwacher brings hand-held intimacy to the chaotic preparations for a confirmation service in a run-down Southern Italian neighbourhood. But the camera becomes contemplatively still when observing Swiss-Italian outsider Marta (Yile Vianello), whose subjective experience dominates Corpo Celeste. Italy’s particular sentimentality towards children is barely invoked.

As a foreign adolescent, Marta turns catatonically inward, seeming mute at first, fiercely refusing to fit into her new home’s strange rites. The Catholic church at provincial ground-level is shown as an exhausted bureaucracy, its priest a bored community pillar and political functionary, clutching his mobile phone more than his rosary, forced into rusty religious engagement by his stubborn, unwanted new charge.

Rohrwacher suggested in a heated Q&A session after its LFF screening that this mix of the “archaic and post-modern” is where Italy is heading. Her film retains enough unexplained moments within its semi-documentary-style – a mountainside ghost town inhabited by a whisky priest, for instance - to confirm a fresh, socially challenging perspective.

Nick Hasted

Eternity

Sivaroj Kongsakul

Thailand 2010

With Wanlop Rungkamjad, Namfon Udomlertlak, Prapas Amnuay

Be it the jungle, farmland or Tsunami-stricken villages, Thailand’s rural landscape exerts a strong pull on the country’s directors, from Apichatpong Weerasethakul to emerging voices such as Aditya Assarat and Uruphong Raksasad. Opening with a serene misty-mountain vista, Sivaroj Kongsakul’s Rotterdam Tiger-winning debut is no exception.

The film is a rather curious and unusual mix, being both a ghost story and a love story. Meandering on his motorcycle into the isolated, lush landscape at the film’s start comes recently deceased, middle-aged Wit, returning to the house he grew up in.

Thai custom has it that the ghosts of the departed return after three days to ‘walk the footsteps’ of the places and moments they most cherished. Wit’s return is to the summer of his youth when he brought his new girlfriend Koi from Bangkok to meet his family, and convinced the shy city girl to live there with him.

Sivorag’s attentiveness to the landscape – largely filmed at the moment when sunlight is squeezed out by dusk – is impressive. His camera is the loitering kind, observing the two lovers from a distance; but while their relationship has its tender moments, it never quite grows intimate or touching enough to justify the melancholy that hangs heavy in the air throughout.

Isabel Stevens

HERE

Braden King

USA 2011

With Ben Foster, Lubna Azabal

An assured fiction-feature debut, HERE is not only a synthesis of King’s previous work in documentary and music video, but a bold endeavour to make a film inspired by a love of map-making and the mythology of exploration. Deliberately playing with style and genre conventions, it sets outs to map the path of love between Gadarine (Lubna Azabal), an ex-patriate Armenian and artistic photographer, and Will (Ben Foster), a Californian cartographer, as they voyage into unknown and unmapped territory in Armenia.

At the film’s core is the concept of map-making itself, or rather film experience as a kind of intimate encounter with another’s ‘map’ of time and space. Cutting across the axis of the film’s romantic drama are non-narrative intervals comprised of over-exposed, jerky, light-emblazoned images: colour-saturated polaroids here, views of Earth from outer space there. These experimental interludes are navigated and narrated by Peter Coyote, anchoring the film historically and scientifically with tales of ancient voyages and the creation of the world’s first maps.

While the film is conceptually dense, the story that unfolds is subtle, sensuous and above all recognisable, in the sense that it authentically recalls what it is like to travel and be caught up in an adventure. And King’s methodology – experimental moving-image art, the mythic and the closely observed love affair – is genuinely rousing, imaginative and sensitively attuned to the technological potential of today’s cinema and its affirming qualities.

Davina Quinlivan, exploring the film on our London Film Festival blog

Last Winter

John Shank

Belgium-France 2011

With Vincent Rottiers, Anaïs Demoustier, Florence Loiret Caille, Michel Subor, Aurore Clément

John Shank’s mesmerising Last Winter is, like most current films about farming, an elegy for a vanishing way of life – but more arresting and more sombre than most. Like Raymond Depardon in his documentary Modern Life, Shank sets his sights on a community of independent farmers deep in the isolated French countryside. Fighting against his fellow co-op members – all elderly farmers eager to sell out – is the fiercely autonomous twentysomething Johann, who has recently inherited his cattle farm from his father.

With the emphasis on Johann’s arduous and often lonely life on the hills as he tries to go it alone, there’s thankfully no room for romanticisation. Barren hills at sunrise never become too serene; indeed, much of the film takes place at night. Shank doesn’t explain much, nor does he let his characters indulge in much conversation; their gnarled, weary faces do the talking.

For some after the festival screening I caught, the film proved too much of a requiem, but not for me. Long after Johann leaves the screen at the end, disappearing off into a wintry expanse, the sheer hostility of the landscape (exquisitely captured by Malick-esque cinematography) stayed with me, as did Vincent Rottiers’s spectacular performance as the film’s heroic but doomed protagonist.

Isabel Stevens

Michael

Markus Schleinzer

Austria 2011

With Michael Fuith, David Rauchenberger

“The paedophile lifestyle drama Michael is, on the surface at least, calm almost throughout. With its superfine control of a stripped-down mise en scène (a typical trait of modern Austrian cinema), Markus Schleinzer’s directorial debut gives us a well-drawn quotidian portrait of a nervy, owlish man who happens to have a male child imprisoned in his basement. Showing how close to ordinary people paedophiles can be, Schleinzer finds room in his otherwise chilly film for pathos, humour and left-field accidents. It’s an appropriately quiet sort of tour de force.”

Nick James, reviewing from Cannes in our July 2011 issue

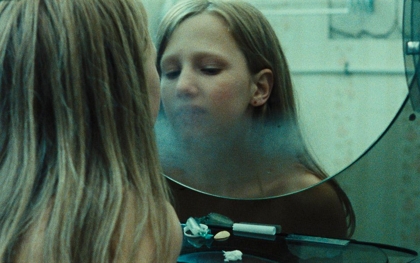

She Monkeys

Lisa Aschan

Sweden 2011

With Mathilda Paradeiser, Linda Molin, Isabella Lindquist, Adam Lundgren

Aschan’s first feature picked up the prize for Best Narrative Feature at the Tribeca festival in 2011, and the film creates considerable momentum from the friendship/desire/rivalry between two teenage girls on a Swedish equestrian gymnastics team. It’s also hypnotically beautiful, making vivid use of the clear Nordic light in its many moods, and similar use of the expressive faces of the main performers, Mathilde Paradeiser, who plays the quiet Emma, and Linda Molin, the confident, bitchy Cassandra.

But the film, confident both narratively and cinematographically, frequently wrong-foots the viewer: Emma is no shy violet, and Cassandra proves both vulnerable and jealous. The tectonic tensions of a teenage female friendship, coupled with strong editing, create moments as tense as fellow Swede Tomas Alfredson’s Let the Right One In. But, having introduced a gun in Act One (both literally and figuratively), it fails to set it off in Act Three: the resolution feels overly elliptical and tentative compared to the confidence of the opening in which Emma trains her dog and rehearses gymnastics, presaging the film's theme of controlled violence, and the violence of control.

It also suffers by comparison to Cecile Schiamma’s Tomboy, also released this year, and her earlier Water Lilies, as it appears to combine the former’s narrative about a younger sister observing her older sister’s emerging sexuality, and the latter’s entry into the well-established genre of lesbian friendship/desire/sporting rivalry films. She Monkeys marks the arrival of a distinctive filmmaker, but I suspect that Aschan’s personal best is yet to come.

Sophie Mayer

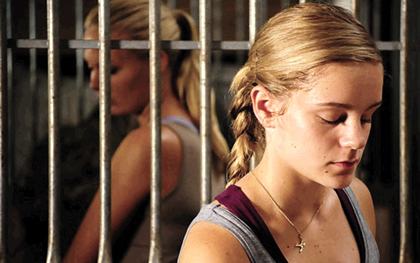

Snowtown

Justin Kerzel

Australia 2011

With Lucas Pittaway, Daniel Henshall, Louise Harris, Craig Coyne, Richard Green

“Based on a notorious true-crime case in Australia and shot where it happened, Justin Kurzel’s film has a fierce, unrelenting power. An accusation of paedophilia against a neighbour brings an intense new father figure, John Bunting (an electrifying Daniel Henshall), into the life of 16-year-old Jamie Vlassakis (newcomer Lucas Pittaway). Jamie’s mother has brought Bunting in to deal with the ‘filthy pervert’ – her ex.

“Bunting gets Jamie involved in the intimidation by having him help dump chopped-up bits of kangaroo all over the neighbour’s front porch and spray ‘fag’ on his windows. The neighbour moves out, but it’s not long before Bunting’s homicidal instincts are turned to others – the general atmosphere of street vengeance seems to give him carte blanche, and Jamie gets increasingly sucked into his grim and gruelling, hysterically violent world.”

Nick James, reviewing from Cannes in our July 2011 issue

The Sun-Beaten Path

Sonthar Gyal

China (Tibet), 2011

With Yeshe Lhadruk, Lo Kyi, Kalzang Rinchen

The Sun-Beaten Path is a kind of road movie, interspersed with flashbacks. The protagonist, a screwed-up young man called Nyima, is returning home from a pilgrimage to Lhasa which has clearly failed to relieve the burden of guilt he carries. He gets off the bus to walk instead, and persistently shuns offers of help from a kindly old stranger, who perseveres with him regardless. We soon find out what’s bugging Nyima: he accidentally killed his mother when he overturned a farm vehicle.

Road movies are traditionally about personal growth, but Nyima is stuck in his trauma, determined to punish – maybe even to destroy – himself. Sonthar Gyal gives the character no easy way out, but the film is not locked into Nyima’s consciousness. Its idiom is what you might call spiritual realism, and it effortlessly frames his difficulties within a larger picture of what’s changing in Tibet – and what will never change.

Tony Rayns, exploring the rise of ethnically Tibetan cinema in our November 2011 issue

See also

London Film Festival blog (October 2011)

LFF 2011: 30 recommendations (October 2011)

LFF 2011: The best live-action shorts (October 2011)