Primary navigation

World Trade Center, director Oliver Stone has re-imagined the real-life rescue of two policemen from the ruins of the towers as a tale of patriotic sacrifice, courage and faith. But is it possible to ignore the subsequent bloodshed, asks B. Ruby Rich.

Oliver Stone's habit of branding American history with his trademark cinematic style made it inevitable that he'd be the one to step up to the task of telling the tale of the destruction of the World Trade Center on 9/11/01, once a decent mourning period had elapsed. What is surprising, then, is not so much the fact of Oliver Stone as the vintage: the director of Platoon (1986), not JFK (1991), is in charge this time around. As a result, World Trade Center (WTC hereafter) is a movie so determinedly circumscribed, so micro-focused, as to constitute not a historical epic but rather a classic disaster movie. Men are trapped. Families await word. Help is on the way. We are at war. Genre trumps history.

A decade ago, I sat on a panel debating Oliver Stone. Organised by the University of California, Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism under the rubric "Reinventing History", this was mid-career Stone, following the release of the last of his Vietnam trilogy, Heaven & Earth (1993), and Nixon (1995).

With the audience cheering us on, we argued over the cinematic relationship between fact and fiction. I dutifully warned against the distortions of historical fact wrought by Hollywood conventions, defending documentary instead, while Stone, citing Plato, declared: "The dramatists came before the historians." (Come to think of it, though, he then went on to make two documentaries: 2003's Comandante and Persona Non Grata.)

It's not so very shocking, then, to find Stone treating the 9/11 destruction of the World Trade Center as, well, a disaster. He and his team comfort their audience - traumatised by the mere act of entering a movie theatre to see this day revivified - with the familiar cues of genre entertainment, smoothly shifting gears between action, melodrama and thriller formulas. The opening credits even sport Hollywood's version of a black armband: small white letters in a sombre font on a black background, devoid of graphics or teaser footage. Then a digital alarm goes off, a man awakens and showers, and the machinery of the plot begins to grind. One guy drives into the city, one takes a commuter train, one crosses the boroughs on a subway. These are the troops of the Port Authority Police Department (PAPD) as well as the tropes we know how to read: this much ordinariness in the morning portends horror or terror or tragedy later in the day. Thus does Stone merge our memory of the date with our memory of every disaster movie we've ever seen. It's The Towering Inferno without the dignitaries, Ace in the Hole without the social critique, a thriller with a foregone conclusion.

WTC is based on the story of two men, Will Jimeno and John McLoughlin, who were the eighteenth and nineteenth individuals out of a total of 20 to be rescued alive from the rubble, and who served as consultants to the production. They couldn't have been scripted any better than they lived it: a veteran and a rookie, one with four kids and the other with a pregnant wife, one Irish and one Colombian, one taciturn and one talkative. They're not only suitable stand-ins for all the New Yorkers who survived or perished on 9/11, but they're perfect movie characters - ordinary guys raised to greatness by extraordinary trials. These are the heroes who will rush from the Port Authority in Midtown to help evacuate the World Trade Center buildings.

Yes, it's a shock to see the screen fill with the towers, still standing on the New York skyline as if they'd never disappeared. To see the smoke and soot, the office papers floating down, and yes, a body falling. To see the movie's characters enter a Concourse magically restored. And then, of course, there's the further shock of seeing it all come tumbling down again, this time experienced from inside, with the film's protagonists, as the ground shakes under them and the building roars and shudders and… well, something more. They don't know what. We, of course, do. And as the screen turns first stark white, then nothing but black, we remember, with a shudder of our own.

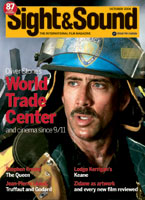

The extraordinary size and scope of WTC's production set (constructed at the Hughes aircraft base at a scale of 1:16) and its special effects succeed in fashioning a time machine that transports us back to the hair-trigger atmosphere of that day, the fear and uncertainty, and the terror of those 13 hours, more or less, between the policemen's initial entrapment and their rescue. What happens exactly in this movie? Given Oliver Stone's steadfast refusal to go where he's gone before in terms of political analysis or investigation, we're left with a streamlined structure and a simplified storyline. Syriana it ain't. Devoid of conspiracies, it's a movie about two men bonded in heroic and patriotic victimisation, I mean, sacrifice. About family men, sustained by the power of love. A drama of triumph and transcendence. Get it? WTC plunges us into the darkness of the buildings' underbelly. There we watch the faces of Nicolas Cage and Michael Peña as John and Will, up-close and rubble-framed, pinned down by debris. Not much to see? Think radio. Cage and Peña talk and talk, embedded in a fairly static environment (well, a fellow officer is killed, more stuff crashes down, some fireballs come roaring through, but otherwise nothing much). They could be stuck in an elevator, a mineshaft or an avalanche. John the sergeant is stoic and internal, Will the new recruit voluble and optimistic. It's good to see Cage, who's become so mannered on screen, reduced to a pair of eyes and a voice while Peña dominates the scenes with his dynamic delivery of Jimeno's reconstructed lines - and, memorably, his hallucination of Jesus with a water bottle.

Underground, then, WTC doesn't seem to care about being a disaster movie; instead, Stone wants to communicate themes of family and faith. Before the jaws of life arrive to free them, John sees visions of his wife, while Will sees Christ. And when they're rescued, the camera gets down in the hole with them, then peers up through a slot that can't help but evoke an association to a grave, as if the rescue were a burial in reverse, the stretcher rising up to the light, the film running backwards through the projector to beam a happy ending for its tale of endurance.

For relief, we wait with the wives. And children. And parents. Or perhaps we wait with ourselves, since they are watching television, and that's exactly what we all did on that day. At one level this is the most predictable and pedestrian section of WTC, with nothing new to offer. On another level, though, it's a brilliant strategy. Five years ago, everyone gasped: "It looked just like a movie." Now the reverse is true: a movie seeking to reinvent that day has to turn to television, specifically to the news coverage of 9/11 where we all learned whatever it is we think we know. Time spent with the families watching TV knits the audience back into the experience of that day and functions as an effective device for constructing the audience members as witnesses. It makes the proceedings more acceptable to us, too, providing all the context Stone has otherwise omitted. The larger story of 9/11 that we might have expected to see enacted in WTC transpires instead on another screen altogether: the parallel screen of the tiny mid-1990s domestic television set.

In a way, WTC seeks to transport its audience back to a moment of relative innocence. But is it remotely possible to return the imagination, even in a movie theatre, to a time before the US government destroyed world sympathy with its invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, before one disaster became many disasters? The US has justifiably enshrined the memory of 11 September, but since 2001 the world has had to memorise other dates, too: 11 March in Madrid, 7 July in London, 12 October in Bali. Perhaps that scope would be too much for any one film, but the narrowcast view of WTC uneasily echoes the myopia of the American public, reasserting US exceptionalism by remembering our disaster, our tragedy, but not yours.

Finally, what WTC most glaringly omits is any sense of cause and effect. Why this uncharacteristic shyness on the part of Oliver Stone? A careful reading of the film's early scene-setting provides some clues as to what deserves follow-up: after the first plane hits, chaos ensues; the PAPD has terrible communication and enters the building without knowing a second plane has hit; the sergeant admits that no large-scale rescue plan was put in place after the 1993 attack on the complex; there is no chain of command, nor any adequate equipment; in Washington, the same chaos is in play; at the FAA nobody knows what to do about the planes, either. Criminal negligence is what this used to be called in the courts. But these sidelong glances are the only bones Stone throws our way.

Coming out of the screening, I wondered most immediately about the buildings' collapse. In The Towering Inferno the blame is pinned on shoddy construction, but I'd never heard any such thing uttered about the World Trade Center. Though Stone hadn't put any such query into his film, the film put questions into my brain. I remember reading at the time about an older steel structure nearby that withstood the flames, put up before the building codes had been changed to allow for thinner steel and less insulation. I remember reading how then-mayor Giuliani had installed an emergency command centre in Building 7, with thousands of gallons of diesel fuel which some guessed must have fed the flames. So I headed to the internet - not to the hundreds of conspiracy blogs, nor to the online documentary Loose Change beloved by conspiracy-minded undergraduates, but to the National Institute of Standards and Technology website. There, in engineering language and steel-stress tests, it's clear there will be changes to the building codes, though all I could put my finger on is a promised update in 2007.

In lieu of raising questions about the buildings or pointing fingers at the government, Oliver Stone sticks with his close focus but makes a detour in a completely different direction: to introduce a character by the name of Dave Karnes, the volunteer who located McLoughlin and Jimeno and guided the rescue team to them. If ever a real-life person existed to be made into an Oliver Stone character, this is it. Karnes is a Marine vet who sees the television news footage in his suburban Connecticut office and declares: "I don't know if you guys know it yet, but this country's at war!" He visits his pastor, tell him the Lord is calling him, gets a regulation haircut, dons his Marine uniform and drives straight to Ground Zero where he enters the disaster site past the other emergency workers streaming out, their search called off by fears another building is about to collapse. "US Marines, can you hear me?" he chants, as he and another rogue soldier patrol the smoking ruins. True story: he found them. Squinting into Oliver Stone's smoke machine, he predicts that some good men are going to be needed to avenge this crime. True story: as the credits roll, we learn that Karnes re-enlisted for two more tours of duty and fought in Iraq.

What's going on here? Despite two hours of realism, melodrama and disaster-movie conventions, Stone cuts loose to create a mythic figure straight out of a Clint Eastwood film. As portrayed by Michael Shannon, Karnes is a prophet and a saviour, a biblical warrior out of the New Testament by way of Vietnam. I have no idea what Stone intends by elevating this figure from the hundreds who did their bit for history that day, but clearly the message isn't lost on the pro-Iraq War right-wing pundits and politicians who used to lather at the mouth with rabid rage over anything Stone did. This time around, they're promoting him. In fact, Paramount has signed Creative Response Concepts, the pit-bull public-relations firm better known for going to bat for conservative causes, to help get word on WTC to folks outside Stone's traditional audience. This is the same company that ran the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth's campaign against John Kerry's Vietnam heroism record during the last US presidential election. I think if I were Oliver Stone, I'd be very worried by now.

Combing the press releases and interviews yields only comments in which Stone emphasises his desire to pay tribute to the brave lads who gave their lives, etc, etc. The tagline for WTC, after all, is: "a story of courage and survival". Now, five years after the US landscape changed forever, his film delivers two absolutely contradictory messages.

On the one hand, it wants to show that Americans were at their very best that day, helping each other and extending sympathy, performing with courage and conviction. In one somewhat over-determined scene, for instance, in a hospital waiting room, McLoughlin's wife Donna (played by Maria Bello) comforts an African-American woman waiting for news of her missing son. In fact, Bello did spend the day at a hospital: she went to St Vincent's with her mother, a nurse, and waited like everyone else for the arrival of the wounded survivors who never materialised. Stone even reminds viewers of that time when the whole world felt for us, inserting a brief montage of ordinary people the planet over weeping in front of their TV screens as the news is announced in a multitude of languages. Ah, those were the days.

WTC delivers the goods of spiritual uplift and transformation in the rescue scene with an unusual stylistic flourish: the camera rises up out of the ground with Jimeno, then keeps going, up into the air for an aerial view of the smouldering wreckage, and onward, up up and away, through the earth's atmosphere to a communications satellite beaming the news. Remember: Stanley Kubrick once made a movie set in this very year, 2001. How far away his Space Odyssey seems.

On the other hand, WTC crashes back to earth as it seems explicitly to endorse the bloodthirsty revenge that has soiled America's hands ever since, positioning a Marine, an agent of war, as the film's saviour. OK, so Stone didn't write the screenplay (first-timer Andrea Berloff did), but didn't he at least listen to the actress who plays Jimeno's wife Allison? After all, Maggie Gyllenhaal nearly lost the part when she made a public statement last year saying US foreign policy bore some responsibility for the events of 9/11. (The real-life Jimeno and his wife forgave her and endorsed her casting.)

Did ex-military man Stone, like Karnes, snap back into some wartime persona and forget all the political positions and conspiracy investigations of his career? It may be hard to explain his motivation, but it's easy to worry about the danger of his influence. The American public already suffers from political amnesia. Stone's WTC could encourage the disconnect of 9/11 from its past and further facilitate its hijacking as a rationale for military aggressions in the present and future.

Any such fear assumes, of course, that the American public goes to see WTC in the first place. A week after its opening it had grossed $26 million. That's just a little bit more than Clerks II, and about $5 million more than An Inconvenient Truth, Al Gore's lesson on global warming. The conventional wisdom would have been that the American people 'weren't ready' to see this trauma replayed as a movie. Paramount clearly thought otherwise. And so did Universal, which released United 93. And Sony, which is now in production on its own thriller-with-the-well-known-ending, 102 Minutes. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, Hollywood studios were famously busy erasing the towers from their about-to-be-released movies and wringing their corporate hands over what Americans would be likely to endure in the locked-in schedule of fall openings. Perhaps it was then that they decided it was their civic duty to memorialise this moment in US history, or perhaps they wagered that Americans pummelled by their government's increasingly global warfare might feel they wanted another look at the day that started it all. Only time will tell if 9/11 will give rise to a whole genre of movies, like World War II did, revelling in a battle once again cleanly drawn between good and evil, or whether it will go the way of the Vietnam War, so divisive and painful as to evade cinematic treatment for years. However, this much is true: the one New Yorker I know who was involved in the rescue operations won't go anywhere near any of these new films. For her, the memories of that time are still pure horror.

Horror? Come to think of it, that might well be the genre best suited, in the end, to reconnecting past and present. It worked for the Cold War years, after all. And certainly waking up in America these days, listening to the news or reading the paper or scanning the internet, the horror is overwhelming. Consider, then, a last bit of persuasive evidence. The writer/producer who actually set WTC in motion was Debra Hill. She read the news reports on McLoughlin and Jimeno's rescue, tracked them down, sat and cried with them and their families, and got their permission to do the film. Tragically, she died of breast cancer just prior to the start of shooting. Hill had collaborated with John Carpenter on Halloween, as writer and producer. She also wrote the screenplay for The Fog, both the original and the remake. And lest you underestimate her influence on WTC's material, she knew her action-thriller formulas too: after all, Hill co-produced the Carpenter film that was released exactly 25 years ago…Escape from New York.