Primary navigation

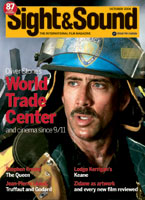

The Queen, directed by Stephen Frears, shows the royal facade crumbling - and Tony Blair relishing his finest hour - as the public mood turns against the monarchy following the death of Princess Diana. By Philip Kemp.

TV drama The Deal united screenwriter Peter Morgan with director Stephen Frears in a study of the shift in power from Brown to Blair. Now The Queen shows how the prime minister was seduced by the monarchy in the days following the death of Princess Diana.

Twice, with increasing unease, the former US president Richard Nixon in Peter Morgan's play Frost/Nixon invokes "the moment when you see it all slipping away." 'It' being power, influence, the capacity to control events. The play climaxes with the famous 1977 television interview in which David Frost manoeuvred the ex-president into something he had stubbornly refused to do at the time of his resignation: admitting his complicity in the Watergate cover-up and apologising to the American people. The tipping point when the balance of power shifts from one person to another clearly fascinates Morgan, both in Frost/Nixon and in his latest film The Queen, directed by Stephen Frears. In Frost/Nixon the key moment comes in a bizarre late-night conversation on the eve of the final interview, when Nixon, apparently drunk, calls Frost in his hotel room and alternately taunts him and claims kinship with him, assuming that Frost shares his sense of paranoia, social inadequacy and class resentment. Up to this point Nixon has successfully blocked all his interviewer's lines of questioning, taking refuge behind a smokescreen of windy, self-justifying guff. But in their last encounter, smarting from the phone call and armed with incriminating transcripts from the Watergate tapes, Frost moves in for the kill.

Morgan's television play The Deal, broadcast on Channel 4 in 2003, dramatises the equally edgy relationship between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, from their first meeting as newly elected Labour MPs in 1983 to the much debated 'agreement' forged at the Granita restaurant in Islington 11 years later when, following the sudden death of John Smith, Brown stood aside to give Blair a clear run at the party leadership. In Morgan's hands the relationship comes to seem like a love affair, starting with mistrust tempered by mutual fascination, maturing into friendship and close political alliance, and ending in betrayal and the lasting resentment of the betrayed party.

The Deal starts by quoting the teasing epigraph that also introduces Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid: "Much of what follows is true." "In the end, whose words do we have to go on?" asks Morgan. "I think we should be much more irreverent about history and enjoy that. I often get nailed by people saying, 'What was or wasn't the truth? Did they really do that? Did they really say that?' Well, in my mind they did. With both Frost/Nixon and The Deal I met almost all the people involved; they were right there in the room, yet they can't agree on a thing. And this is recent history, not the Tudors, so what hope has the historian got? There's every chance that someone coming in and creating a fiction could be more accurate." Once again the drama pivots on a key tipping point, when power shifts almost imperceptibly but irrevocably from Brown (David Morrissey as a brooding, granite presence) to the seemingly more lightweight but far more adaptable Blair. Blair is played, in a performance that subtly inhabits rather than mimics the original, by Michael Sheen (who also plays David Frost in Frost/Nixon), and The Deal was directed by Stephen Frears, with all his understated and easily underrated sense of pacing and structure. Now the three - Frears, Morgan and Sheen - are reunited for what might be seen as The Deal's unofficial sequel, The Queen, which focuses on the relationship between prime minister and monarch during the week after the death of Princess Diana.Being a film rather than a television drama, The Queen benefits from the wider sense of visual and dramatic space that comes with cinematic compositions and a more lavish budget. The dynamic structure is more complex, too: not a single shift in the balance of power but a pendulum swing, one way and then poised to start back. Though the main part of the film concentrates on that crucial week in early September 1997 following the moment when the car carrying Diana and Dodi Al-Fayed crashed in a Paris tunnel, the action is bookended by two royal audiences. In the first, played for social comedy, the newly elected Blair calls on Queen Elizabeth II to be invited to form a government. Quivering with nerves and over-eagerness, he commits several errors of protocol, observed by The Queen with unruffled, kindly amusement. He is never allowed to forget - and nor are we - that while he's a callow newcomer to his job, she has been performing hers with growing expertise for nearly half a century. Nothing can throw her - or so it seems.

Other portrayals of The Queen, such as Alan Bennett's affectionately ironic sketch in A Question of Attribution (1991), have plausibly caught the public persona - shrewd, quietly humorous, but at all times in perfect control. Morgan's script digs behind that carefully constructed facade, showing us The Queen gradually losing control and unable to deal with it. Shut away in the fusty, Teutonic-baronial gloom of Balmoral, blinkered by their personal dislike of the dead princess, she and her family fatally misjudge the mood of the country. To her dismay, she finds the extraordinary flood of lachrymose hysteria - in itself distasteful to someone schooled to suppress emotion - turning to mass hostility towards the House of Windsor, much of it stoked by tabloid newspapers which get read in Balmoral. "I've never been hated like that before," she murmurs, shaken. Stephen Frears, always an exceptional director of actors, draws from Helen Mirren a performance that even convinced republicans may feel moved by.

Tony Blair, meanwhile, still buoyed by the euphoria of his election victory, rises triumphantly to the occasion with his 'People's Princess' speech. "Blair was Mark Antony at that moment," says Morgan. "It was his highest point." His stock soaring even as The Queen's plummets (and egged on by Prince Charles, working out his resentment against his mother), Blair starts doing something he'd have found unthinkable only a few days earlier: gently browbeating the Queen, urging her to ditch protocol, lower the royal standard over Buck House, agree to a state funeral and make a public statement about Diana, which is livened up by Blair's spinmeister Alastair Campbell.

She capitulates on all points, but she doesn't forgive. In the second audience, set several weeks later, it's Blair's turn to misread the mood. He enters chatting, almost gushing, assuming a bond between them in the wake of recent events. The Queen receives him with a formal chill that repels the least hint of familiarity. The balance of power during those few days may have shifted in his favour, but, she warns him, it won't last. The transient affection of the public is all too capable of turning against him, too. "And it will, Mr Blair," she tells him with more than a hint of Schadenfreude. "Quite suddenly and without warning."

"I like writing about powerful people," says Morgan, "and the inner lives of powerful people. I always think my stuff is about friendship and betrayal, but it's also about unlikely love stories between unlikeable people." So in this odd-couple relationship between the prime minister and The Queen, what we ultimately see happening is the seduction of Tony Blair by the myth of the British monarchy. To begin with he seems inclined to go along with the view of his wife Cherie that the royals are "a bunch of freebooting, emotionally retarded nutters". But as passions rise in the aftermath of Diana's death, and the press - desperate to deflect any accusations of responsibility for the accident - swell the anti-Windsor chorus, Blair begins to feel it is his duty to preserve the royal family from its self-destructive instincts. "You've gone weak at the knees," says Cherie (portrayed here more sympathetically than usual). "All Labour prime ministers go gaga over The Queen."

Like The Deal, The Queen is serious but not solemn. While there's no descent into Spitting Image-style caricature, funny moments abound. The Queen herself is allowed to be mildly bitchy ("I don't measure the depth of a curtsey," she says while waiting for the Blairs to pay their first visit. "I leave that to my sister.") As Prince Philip, the imaginatively cast James Cromwell gets some cherishable lines. ("Move over, cabbage," he grunts, sliding into bed alongside HM.) Sylvia Syms as The Queen Mother counsels fortitude, but is shocked when a courtier suggests that certain funeral arrangements codenamed 'Tay Bridge' should be adapted for Diana's obsequies. "But that's my funeral!" she exclaims, outraged.

Even so, the royals are portrayed as a pitiable clan, locked into patterns of tight emotional repression. (At one point we cut from the stiff, formal dining room at Balmoral to Cherie dishing up fish fingers for her family in a cheerfully cluttered kitchen.) Prince Charles, convinced people are trying to assassinate him and ducking nervously when a motorbike backfires, talks wistfully of Diana as "always warm, never afraid to show her feelings", obviously contrasting her with his own parched background. Lying in bed, The Queen watches footage of Diana on television with an air of faint puzzlement, as if studying an alien species. Meanwhile Prince Philip's choice of therapy for the young princes' grief is to haul them up on to the moors to take pot-shots at anything that moves. "Do 'em good to get 'em out in the open air," he asserts breezily.

But ultimately The Queen is a shrewdly balanced two-hander between Michael Sheen's uncannily exact impersonation of Tony Blair and Helen Mirren's note-perfect performance as The Queen. Initially, according to Morgan, more screentime was devoted to Mirren. "We looked at the first cut and it was her film. One of the producers said, 'Right, to get a shot at the awards we need to do some extra shooting on Helen - give her a big scene in the first third.' And I thought, OK, but that's not what I think is wrong with the film. So I said, 'Well, I'd like to write some more stuff for Tony Blair.' And Stephen said - and I'll always love him unconditionally for this - 'You're right'." "So we shot four extra days just of Tony Blair. Helen's performance is exactly as it was, but the net effect was that they set each other off, so it was almost as if we'd shot four more days on Helen, too."

Morgan, whose career in screenwriting dates back to the late 1980s, is impressed by Frears' total involvement with his projects. "Working with him is different from working with anyone else because he drives you so hard. I'd even be taken on recces - and for a writer to go on recces is just unimaginable. So your emotional attachment deepens and deepens."

This commitment made The Queen a more satisfying experience than other films Morgan has worked on. Generally he prefers writing for the small screen. "In television you get a chance to be responsible for your writing. You can't duck it, or say, 'Oh, that's the producer, or the director' because what you've written will largely get shot. But as the screenwriter, you become a navigator of other people's responses. You're no longer the architect of your own narrative; you're dealing with and juggling other people's input. The wonderful thing about The Queen, as with The Deal, is that Stephen has the power to arbitrate, to say, 'Well, I've heard all the different versions and this is the one we're going to do.'

Peter Morgan's work seems to be everywhere at present. Due for release later this year is another feature film The Last King of Scotland, scripted by Morgan and directed by Kevin Macdonald, famous for documentaries such as One Day in September and here making his first feature film. Frost/Nixon is playing at London's Donmar Warehouse, and shortly to appear on television is Longford, dealing with perhaps the oddest-couple relationship of all, between anti-porn campaigner Lord Longford and Moors murderer Myra Hindley, and featuring Jim Broadbent in the title role. Historical drama The Other Boleyn Girl is in pre-production. And Morgan is intrigued by the idea of reuniting with Frears - and no doubt Sheen - for a film about the prime minister's relationships with Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Blair III - The Downfall? It's worth looking forward to.