Primary navigation

USA 2004

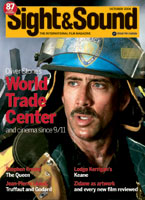

Reviewed by Tom Charity

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

New York, the present. Thirtysomething Keane haunts the Port Authority bus terminal, the site of his daughter's abduction some months previously (or so he says). Obviously in anguish, and apparently mentally unstable, he presses his daughter's photograph on passing commuters hoping for some sign of recognition, then attempts to retrace the route she may have taken on the day she disappeared. He ends up in the road, standing in the traffic, shouting his daughter's name.

He lives in a cheap flop-house that he pays for out of a disability cheque. He attempts to keep himself presentable for the day he is reunited with his daughter; sometimes he even buys her clothes. Other times he turns to cocaine or alcohol. Always he is drawn back to the bus terminal.

Keane notices fellow lodger Lynn and her six-year-old daughter, Kira, arguing about money with the desk clerk in his hotel. Later he persuades Lynn to accept $100. She says the girl's father moved away to find work and a home for them two months previously. Lynn asks Keane to pick up Kira after school so that she can sort things out. He does so, but Lynn does not return that night. The next morning he takes Kira skating and bonds with the child. When Lynn returns she says she and Kira will be leaving the next day to start their new life. Keane picks up Kira early from school and takes her to the bus terminal, where he re-enacts his last moments with his daughter, purchasing two bus tickets and allowing the girl out of his sight. But he cannot go through with the plan, and tells Kira they will go and find her mum.

Do you remember me? The man at the bus terminal needs to know. He is pale. Agitated. Imploring. The woman behind the ticket counter turns to a colleague. It was last September, he tells them. My little girl was abducted. They listen politely. Apologise blankly. He plunges on, talking to himself now, pressing a photograph on strangers, looking for an abductor in the crowd, grasping at clues that aren't there.

It is crucial to the experience of Keane the character, played by Damian Lewis, and Keane the movie, directed by Lodge Kerrigan, that unlike the commuters going about their business in New York's Port Authority building, the viewer is not permitted to step back or look away. A handheld camera connotes realism, and sometimes allows it. But there are degrees of reality. In Keane the camera focuses so closely on its lead character's face you can practically feel his stubble. It's not a vantage point from which to observe, but an act of reckless identification, or an annihilation of personal space (whether his or ours is a moot point) often associated with so-called street people. Granted there may be many valid reasons for treading carefully, but not in the security of the cinema, where imaginative trespass can be good for the soul. If Belgium's Dardenne brothers could claim to have patented something very similar to this brand of walking over-the-shoulder shot (and the urban industrial ambient drone that goes with it), real-time is equally critical to their experiential ends. Kerrigan gives the technique the jolt of repeated jump cuts and whip pans, a spasmodic, disorientingly loopy syntax in synch with his hero's ongoing nightmare; it is ten minutes before the director allows him (and us) to retreat into long shot, as Keane is swallowed into the impervious black hole of a road tunnel.

The sense of concentration remains intense. There is barely a shot in which Keane does not appear or is not implicated. It's only after about 30 minutes of mounting futility and desperation, culminating in a paranoid attack on a random stranger, that Kerrigan throws his audience a narrative bone: the pivotal encounter with Lynn and her young daughter Kira, fellow lodgers in the flophouse where Keane lives. Milked for suspense, this development might seem forced (would Lynn really entrust her child to Keane's care?), but the viewer's suspicions and doubts are entirely wrapped up in Lewis' raw, harrowing embodiment of a character concurrently amped up (he's almost never still) and wiped out. We know this man is every bit as lost as his daughter, and fear he may be capable of some untold terror. He is too wounded, too hungry and alone. Perhaps he means to use Kira as bait, or to snatch her away himself? Kerrigan withholds so much that the question insinuates itself - did he even have a daughter in the first place? The tension is there all right, but Lewis also supplies the movie's saving grace: the way Keane, with Kira's mother absent for a day, makes the girl eat up her meal before dessert, teaches her numbers, washes her hair… Keane's gentle care proffers some hint of salvation, so that this dark, 'difficult' film may end on a declaration of love.

It is interesting to note that in executive producer Steven Soderbergh's alternate cut (available as an extra on the Region 1 DVD) Lynn and Kira make an earlier appearance, and that bruising opening salvo in the Port Authority is shifted well into the body of the movie and sliced into shorter, more manageable scenes. Soderbergh's structure is arguably more rational, while Kerrigan's is both more demanding and more powerful. Intriguing as Soderbergh's cut may be, a more revealing comparison is with Kerrigan's first film, the widely admired Clean, Shaven (1993). Another intense study of a mentally frail man separated from his daughter, the earlier film is predicated on the suggestion that the 'hero' is himself a child abductor, only to undercut that assumption in the last scene. Almost unwatchable at times, Clean, Shaven is a more extreme, expressionist exercise in paranoia, but it's also inherently schlocky and sensationalist, a bit of a cheap trick. Granted that Peter Winter, the protagonist in the earlier film, is much further gone than his counterpart in the new one, it is hard not to read Keane as self-critique, a more mature, compassionate treatment of an abiding concern for those marginalised souls and damaged psyches in danger of slipping through the cracks.