Primary navigation

American television drama is much lauded for its risk taking and authorship but, argues BFI curator Mark Duguid, comparisons with British small-screen drama are distracting us from our own new ‘golden generation’ of gifted writers

Last August, Tory shadow home secretary Chris Grayling compared parts of inner-city Britain, particularly Manchester’s Moss Side, to The Wire’s west Baltimore. The HBO series, he said, “used to be just a work of fiction for British viewers. But under this government, in many parts of British cities, The Wire has become a part of real life in this country.”

I mention this episode partly to meet a critical obligation. As wearied media watchers will know, it has become unthinkable to consider the state of British television drama without reference to The Wire. Grayling’s analogy was absurdly disproportionate, as most coverage pointed out, but his comments indicate that the outbreak of prostration before US drama that started within a small section of the cultural commentariat has now jumped the species barrier and begun to infect the political class.

“They get The Wire, we get Casualty,” complained one Guardian blogger last October (which, as fair comparisons go, runs a close second to: “We get Shakespeare, they get Dan Brown”), while in the paper, when news broke in February of the BBC’s strategic review proposals to reallocate up to a third of the £100 million imports budget to quality new drama and comedy on BBC2, a horrified Lucy Mangan cited low-rent sitcom Two Pints of Lager and a Packet of Crisps as the reason why licence-payers’ money is better invested overseas than at home. The Independent, meanwhile, last year heralded a US television ‘golden age’ and asked: “Where are the BBC’s homegrown equivalents of Mad Men, The Sopranos or Six Feet Under?”

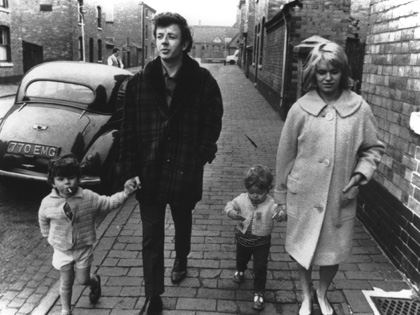

Jeremy Sandford’s Cathy Come Home

And if it’s not one golden age, it’s another. Today’s writers are used to unfavourable comparisons with a mistily remembered era when British small-screen drama was as mighty as it is now apparently meek. This cultural paradise is generally deemed to have lasted from the early 1960s to around the mid-1980s – roughly the lifespan of the BBC’s Wednesday Play and its successor, Play for Today. Serious television drama, it’s assumed, has been slowly becoming extinct ever since.

Last summer, in an email that ricocheted around the industry, esteemed television veteran Tony Garnett charged the BBC with “stifling creativity” in drama writing. He painted a bleak picture of an organisation riddled with management consultants, in which power had migrated to the top of a tall pyramid, leaving hapless writers fending off “totalitarian micro management” and reduced to “executives’ scribes”. Garnett’s email eventually found its way into the broadsheets, where it usefully slotted into the prolonged BBC-under-siege narrative alongside Sachsgate, the salaries crises and the relentless Murdochian crusade.

The pressures may be real. But the more astute observers, including Garnett, recognise that whatever problems British television faces, it’s not a deficit of writing talent – a point dangerously obscured in the less-nuanced debate in the press. I’d go further: what if, despite difficult circumstances, a new golden generation of writers had emerged but we were failing to notice it? A second wave of television authors markedly different to, but capable of matching, the hallowed coterie of Alan Plater, Dennis Potter, Troy Kennedy Martin et al?

That’s the contention driving BFI Southbank’s two-month ‘Second Coming’ season, which begins in May – that far from being an age of stagnation, the last decade has witnessed the maturation of a generation of dramatists every bit as talented as their ‘golden age’ forebears. Writers like Russell T. Davies, Paul Abbott, Jimmy McGovern, Guy Hibbert, Tony Marchant, Abi Morgan, Peter Moffat, Dominic Savage, Rowan Joffe, Donna Franceschild, William Ivory, Jed Mercurio, Peter Bowker and Neil Biswas have all grown up with television and produced highly distinctive work that restlessly explores its possibilities (even if, yes, there is still too much unchallenging, formulaic work churned out by less able, less ambitious or, perhaps, more constrained writers). Most are still relatively young, and still getting better. Their misfortune has been to come to the fore at a time of structural and financial uncertainty for UK drama and while British critics are transfixed by transatlantic fare.

British television criticism has always been a shallow discipline by comparison with criticism of film or theatre, its columns casually assigned to those ignorant of and indifferent to the history of a medium that many seem to hold in something like contempt. It’s telling that its two most celebrated practitioners, Clive James and Nancy Banks-Smith, are primarily admired for their wit. Following their example, most of today’s exponents – with one or two honourable exceptions, such as the Independent’s Tom Sutcliffe – favour humour, venom or writerly flourish over depth or insight, frequently overlooking drama altogether because reality formats are a better source of gags.

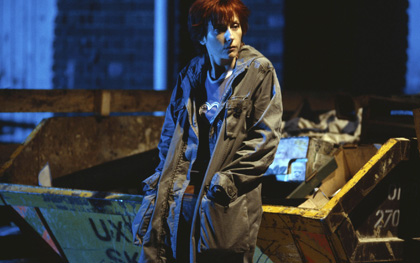

Guy Hibbert’s May 33rd

There are, then, two quite separate strands to the debate around television drama that urgently need disentangling. First, the structural issues raised by Garnett are serious, but the most intelligent discussion of them is happening among those who know broadcasting from the inside. But the second strand, the complaint that today’s British drama is inferior both to a lost idyll in the UK (Garnett, to be fair, rejects this rosy nostalgia) and a creative resurgence across the Atlantic, is on the one hand historically questionable and on the other coloured by a predisposition against British television.

Plainly, television drama no longer holds the privileged status it once enjoyed. Audiences have shrunk in the face of multiplying distractions, while the pendulum of commissioning has swung away from drama towards more lucrative reality formats and talent shows. There is, in general, infinitely more media content, mostly execrable.

Regardless, the ‘golden age’ refrain has become television’s equivalent of ‘dad rock’ – an older generation’s conviction that things (The Beatles, The Wednesday Play) were just better back in their day. Television has always had its share of landfill: the same BBC drama department that produced Boys from the Blackstuff was at the same time screening the second of three series of cross-Channel-ferry-disaster drama Triangle.

As for the contrast with America, while there’s no denying the merits of The Wire, Mad Men, The Sopranos and Six Feet Under, it’s only reasonable to accept that we see only the best that American television has to offer. What’s more, critics seem to have invented a bizarre form of Newtonian physics by which any advance in the quality of drama on one side of the Atlantic must result in an equal and opposite decline on the other.

That Casualty/The Wire parallel reveals only that, for the most part, the best British drama remains in the single pieces, two-parters and short serials where our small-screen auteurs have traditionally felt most at home. There may be problems with this, but it is unfair to fail to acknowledge the power and breadth of work like Boy A, Dirty Filthy Love, Donovan Quick, Endgame, England Expects, Faith, Five Minutes of Heaven, Flesh and Blood, The Government Inspector, The Mark of Cain, Out of Control, Second Generation, Secret Life, Shoot the Messenger, Tina Goes Shopping and White Girl – and that’s in singles alone (and only one work per writer).

Sharon Foster’s Shoot the Messenger

In the last few months I’ve spoken to around a dozen television writers as background research for the season. All recognised elements of the world Garnett described. A couple strongly supported his intervention, but more were quite critical; two had already written publicly in support of the BBC (risking cynicism about their motives). Consensus can be hard to find among writers, but all agree that things are more difficult now, that television has been warped by the values of the marketplace. But they are also, for the most part, more optimistic than you might expect.

Among the grounds for that optimism are the noises coming from BBC2, which, under Janice Hadlow, is charged with restoring quality drama: she has publicity cited Our Friends in the North and Edge of Darkness as models. Though some remain to be convinced – like Our Friends creator Peter Flannery, who worries that “we’ve all bought into the idea that something on that scale cannot be done again” – others are taking the BBC at its word.

Guy Hibbert remembers ruefully an earlier BBC2 that plundered the drama budget to fund populist non-fiction formats like Who Do You Think You Are? and Restoration, boosting the ratings but crippling the less mainstream drama projects that had once flourished there: “It was criminal for them not to do drama on BBC2,” he says, “it was killing everybody off.” But now, Hibbert continues, “there is a proper BBC2 drama budget, and suddenly we can start feeling creative again.” Hibbert’s most recent works, March’s bold, ambitious analysis of Nigerian corruption and western exploitation, Blood and Oil, and last year’s outstanding Five Minutes of Heaven were both for BBC2.

“I think we’re coming into a good period with these latest reviews of the BBC and drama,” echoes Dominic Savage, writer/director of Nice Girl, Out of Control and the forthcoming Dive. “I think it can only be for the good.” Tony Marchant, writer of Holding On, The Mark of Cain and the recent Garrow’s Law, was not the only screenwriter to announce with some relief that the BBC, under its youthful head of drama Ben Stephenson, is “genuinely talking about authorship again”.

Tony Marchant’s The Mark of Cain

Marchant points out that authorship, in the British context, has meant singles and short serials, and only rarely series. There is a real frustration that what might have been an evolution in this respect in the early 2000s – when Peter Moffat’s North Square, Jed Mercurio’s Bodies and Steve Coombes’ Outlaws were all given at least ten parts – was cut short by commissioners with unrealistic expectations of audience reward. Of that era, only Paul Abbott’s Shameless survives – a major prop for Channel 4, but detached from its creator and well short of its early greatness. The later 2000s saw a retreat to two-, three- or four-parters, with rare exceptions like Abbott’s majestic six-part State of Play. Latterly, though, there are signs in successes like Gwyneth Hughes’ Five Days and Moffat’s Criminal Justice that authored works are getting a little longer and are capable of delivering returnable formats. British writers seem increasingly ready to stretch out. “The desire to make my own long-runner is becoming much stronger,” says Abi Morgan, writer of Sex Traffic and White Girl, while even Dominic Savage, hitherto strictly a singles man, is making the leap to two- and three-parters.

We might have to accept, though, that sprawling authored work isn’t a natural British form, just as our novelists don’t perpetually strive for the Great British Novel. Anyway, how realistic is competing with America? Budgets north of $3 million an episode are typical there; HBO’s new The Pacific set new records at a reported $20 million per episode. Compare that with the very top end of the BBC’s ‘tariff’: £900,000+ per hour for ‘premium drama’ (“bank holiday events; specials or landmark commissions”); £700-900,000 per hour being the more common benchmark for ‘high-cost drama’ (the likes of Spooks).

Budget inflation is arguably a large part of the problem. Bigger budgets for some dramas means others suffer, while Tony Marchant, for one, fears we are being trained, not least from US imports, to expect drama of slick, impeccably high production values, where the stakes are too high to contemplate failure. He argues that “it is worth embracing a guerrilla style of making television drama” to fight off some of the “CCTV” from executives. This, Marchant hopes, is happening away from BBC1 in modest-budget, high-concept series like BBC3’s Being Human, E4’s Misfits and Channel 4’s Cast-Offs.

Devotees of American drama stress its ambition and sophistication, but rarely admit another key element of its appeal: the enduring glamour and otherness surrounding a culture at once familiar and distant. The appearance of British actors within this arena only adds to the fascination – especially when they’re actually playing English, as in Mad Men. Whatever we might expect of British drama, it can never match this aura.

Rowan Joffe’s Secret Life

What we might learn from, though, is the American showrunning concept, in which one writer drives a series, working with teams of other writers while shaping the results to his (female examples seem hard to find) overall vision. “That’s where the Americans are getting this right,” says Rowan Joffe, writer of Gas Attack and writer-director of Secret Life. “Writers are well placed to become producers… given the grip they have on the nature of their work.” Abi Morgan, too, is attracted to the idea of showrunning, but wonders whether British television has yet offered the real deal: “Writers are demanding and being given executive producer credits,” she acknowledges, but “you’ve got to make sure that’s not just a vanity title.”

So far, Russell T. Davies’ (former) position on Doctor Who represents the purest British application of this model, although Skins overseer Bryan Elsley is perhaps close, as is Jimmy McGovern on The Street. McGovern, currently developing a new series, The Accused, with a similar multi-authored, multi-story structure, is convinced that “the future is showrunning”, but is frustrated by a sense that the British are trying to do it on the cheap. “You end up subsidising independent production companies or maybe even the BBC,” he says, noting that the Americans devote a far larger proportion of the budget to scripts: “The showrunning approach should be much more expensive than it is [treated as being in the UK], and the BBC have yet to grasp that nettle.” This view is echoed by William Ivory, who admits to “mixed feelings” about the quasi-showrunner role he had on last year’s The Invisibles: “There wasn’t really the time or the money to make the thing work on the American model.”

Such issues have been exercising Gub Neal, former producer, one-time Channel 4 head of drama and founder of independent Box TV. A year ago, with three former Box colleagues, he set up Artists Studio as, he says, “a vehicle that would allow writers to be completely proactive in propelling their own projects”. This means championing the showrunner model where it fits: “It’s a great model because it depicts the creative as a grown-up. It gives the writer as a producer a sense of responsibility and accountability and control.” Among his clients are William Boyd, Simon Block and William Ivory; Ivory relishes developing a project into a full package, with key decisions about budget, casting and direction fixed before a broadcaster or production company gets involved: “It’s a fantastically sensible arrangement.”

But the single-author model remains preferable for some, including Peter Moffat, who believes The Wire’s success is opening doors for more ambitious solo projects too. His own recent commission, The Village, is a case in point, and the most intriguing developing project I’ve come across. The story of an English village and its people, it is envisaged as a long-form narrative (initially six parts, with a view to 24 in all) in the manner of Edgar Reitz’s epic Heimat and redolent of Adam Thorpe’s novel Ulverton or Ronald Blythe’s social history Akenfield.

Donna Franceschild’s The Key

I’m not arguing that all is perfect. Though my interview sample was inevitably skewed towards the most successful of today’s writers, there were sour notes. Anecdotally, I heard of talented writers killing time on derivative series and of promising newcomers unable to get a foot in the door. Others seem to have inexplicably fallen out of favour. Donna Franceschild, writer of the glorious Takin’ Over the Asylum, has had nothing produced for television since 2003’s three-part The Key, which may have been her masterpiece (thankfully, she now has a work close to development).

Equally worrying is the continued whiteness of television dramatists. Black and Asian writers are thriving in theatre, but in television they are scarcer than ever. Sharon Foster’s challenging and very distinctive debut, Shoot the Messenger, was one of a tiny number of television dramas by a black writer in the past decade; Foster has worked little in the medium since. The sole new arrival to make a lasting impact is Neil Biswas, whose Second Generation offered a dissonant take on the turn-of-the-millennium Asian-British boom, and whose recent The Take has been much praised.

These problems and many others need to be confronted. Because British television drama matters. Though American drama may deal with universal themes, we also need drama that reflects our specific lived experiences and social problems, drama that can help to combat the alarming deficit of empathy that distorts public understanding of, say, criminality, abuse or injustice (something that I’m not convinced much American television, however sophisticated, does). It’s up to the broadcasters to nurture good writing and give it what it needs to shine. But it’s up to the critics – and us – to recognise excellent work when it’s there. Otherwise we will all be left like Chris Grayling, deludedly scouring American television for explanations of British issues, adrift and bewildered when the analogies fail to fit the reality.

The ‘Second Coming: The Rebirth of TV Drama’ season runs at BFI Southbank, London until 25 June

Down in the hole: Kent Jones on The Wire (May 2008)

Channelling the past: Alkarim Jivani interviews Channel 4’s founders, 25 years on (December 2007)

Funny games: Andy Medhurst remembers the radical television comedies of the 1980s (November 2000)

Send in the clowns: Rob White revisits 1979’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (October 2000)

Blues in the night: David Jays revisits Dennis Potter’s Pennies from Heaven (September 2000)