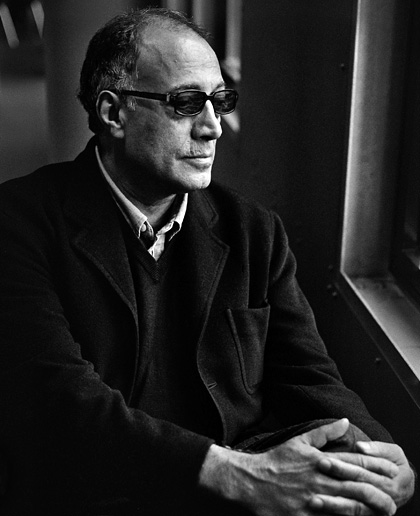

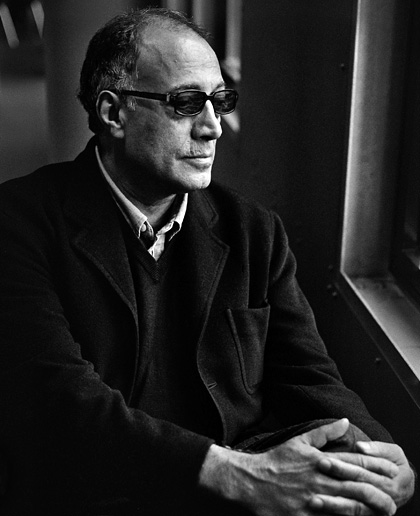

Restoration comedy: Abbas Kiarostami’s ‘Certified Copy’

Both a romantic comedy and a vehicle for Juliette Binoche, ‘Certified Copy’ seems a departure for Abbas Kiarostami, but its playful ambiguity makes it very much his work. Geoff Andrew talks to the Iranian director and his star

A great deal has been made of how Abbas Kiarostami’s latest film Certified Copy (Copie conforme) differs from his previous work – of its being both his first full-length feature shot outside Iran and his first film to boast a movie star. One should, however, bear in mind that Kiarostami has worked outside his native Iran before now (not only on the documentary A.B.C. Africa and on his brilliant contribution to the Italian-set portmanteau film Tickets, but on the Spanish promenade episode in Five and, rather more obscurely, on a subtly virtuoso beach sequence in Pierre Rissient: Man of Cinema, Todd McCarthy’s portrait of the critic, film-maker and festival-circuit fixture). The star in question, meanwhile, is Juliette Binoche, who (like Isabelle Huppert, who lent her voice if not her bodily presence to Kiarostami’s short Lumière et compagnie) has repeatedly sought out original, audacious and top-notch international directors to work with.

While Certified Copy may be an unprecedentedly high-profile addition to Kiarostami’s oeuvre, it’s still as quirkily personal, playful, artisanal and attentive to small, intriguing details as anything he’s made. Indeed, for all the talk of ‘a rom-com with a difference’ that greeted its Cannes premiere, it’s the difference from other people’s work rather than from his own that should probably be stressed. Rossellini (Journey to Italy) and Richard Linklater (Before Sunrise and Before Sunset) have both been adduced as reference points, but such is the level of ambiguity in Certified Copy that it’s finally impossible to imagine it having been made by anyone but Kiarostami.

The film, made some years after Binoche first suggested they work together, is set in Tuscany, and chronicles a day in the life of a French-born antiques gallery owner and an English author who’s in Italy to promote his book on originals and copies in art. After he delivers a short lecture, he visits her in her shop, and they drive to a nearby village, discussing all manner of things: art, work, children, men, women, love, happiness. In a café, the proprietor assumes the writer is the gallery owner’s husband; is the woman any more likely to be incorrect in her reading of their relationship than we the film’s audience have been?

Certified Copy covers a range of Kiarostami’s concerns to do with male-female relationships, life and art, presence and absence, reality and representation, while its deceptively naturalistic narrative is built on a typically meticulous mise en scène that includes a long conversation in a car, much mischief with re?ections and frames within frames and some sly play with perspective. It also offers some superb acting – particularly that of Binoche, who deservedly won this year’s Best Actress prize at Cannes – which is where my interview with Kiarostami took place.

Juliette Binoche and William Shimell

Geoff Andrew: You’ve said the film was inspired by a real encounter, but you’ve been leaving it unclear whether it actually involved yourself or someone else.

Abbas Kiarostami: It is actually based on something that happened to me ten, 15, maybe even 20 years ago – I’ve no real sense of time. And I wonder whether the woman in question, if she sees the film, will recognise herself. Is it just a memory I myself kept from what happened? After all, we spent just one day together – I wonder whether she’d remember it at all. I did see her once again, in the audience at a press conference for one of my films. I waved as if to say “see you later,” but then I was taken out by a door the audience wasn’t allowed to use, so I never got to talk to her after all. So that was it.

What was it exactly that you wanted to develop from this story?

It’s funny – I can no longer even remember why I happened to tell Juliette this story when she came to Tehran. I just started relating it to her as an anecdote, and I was struck by the strong, rich reactions on her face. In a sense the expressions you see in the film echo her reactions when I first told her the story. It’s like when you have guests to dinner – if they like your food, you want to serve up some more. That’s what I did here: in reacting to her reaction, I gave her some more of the story. It’s as if the story just became a script. If I’d told it to someone else, I’d never have realised it could be made into a film. There’s a Persian poem that roughly translates as, “The listener made the speaker enthusiastic.” Whatever’s most interesting about something you’re saying is utterly dependent on the listener and their reactions. So we really owe this film to the quality of attention Juliette paid to the story I told her.

Juliette Binoche is the first star you’ve worked with. Did you give her much direction?

Not really, though at the beginning she had a lot of questions – and some doubts – so we did go through that process of how to approach her character. At first she seemed to rely on models – Anna Magnani, for instance – and that could have been troublesome because I didn’t want her to refer to anyone else. I kept saying, “This woman you’re playing is no one but Juliette,” but for a while she wouldn’t have that. So I said, “OK, if there’s any scene, or even a line, in which you don’t recognise yourself, let me know and I’ll take it out.” Then she came to realise and admit that the woman was her.

But even after our Cannes screening – and I find this very touching – she confessed to me that she was still worried: “I don’t want people to think I’m like her.” I said, “Well, you don’t have to admit this to anyone, but for two months you were her and she was you – not only when we were shooting, but 24 hours a day.” She really put her heart into the film – it wasn’t just professional acting, it was all about her. That said, we must remember that today’s Juliette is not last summer’s Juliette!

William Shimell, who plays the English writer in ‘Certified Copy’, had only acted in opera before. Did you direct him differently?

I myself think I didn’t really direct anyone. Maybe at the beginning with William I was a little concerned, because at some point in rehearsals I felt he might resist – that perhaps he didn’t want to let himself go or didn’t want to admit some aspects of the character. But I then realised that it simply took him a little time to make the character really his own. So I gave him that time. And whereas the film was written for and tailored to Juliette, that wasn’t the case with William. It took some time to cast that role, but the day I saw him, I knew he was the one, and once you’ve the right person in the part there’s not much to do.

This was the first time you’ve written a detailed script for one of your films.

I did it because I had to, to get funding for the film. But then I felt quite grateful for that, because it provided something I could rely on. Up till now, as my own producer, I’ve been fairly easy-going and let the director do whatever he wanted. But perhaps from now on I should be like [producer] Marin [Karmitz] and demand a script!

When shooting, did you stick closely to the script, or was it just a springboard?

The first part we kept pretty much as it was written. But the second part we left quite open, especially as we weren’t sure how much time we’d have left to complete the shoot.

After she’d read the script Binoche told me it reminded her of Bergman’s ‘Scenes from a Marriage’. She’s right in that your day in the life of a man and a woman resembles a whole relationship, from flirtation to forgetfulness, resentment and recrimination.

That’s interesting. I haven’t thought about that film for years. But I did see it a long time ago, and I remember immediately wanting to watch it again. So maybe it was a subconscious in?uence!

Why did you sometimes choose – especially in the restaurant scene – to have Juliette and William speak more or less directly to camera?

I know that doing that risks making things look a bit artificial, but you have to take risks. My aim was to have Juliette speak directly to the male spectators in the audience – it was as if I wanted them seated just in front of William – and to do the same with him and the women in the audience. So when we shot the restaurant scene, we took a table for four and had Juliette and William sitting diagonally across from one another, each facing a camera which was next to the other actor. So while they couldn’t quite look directly at each other, at least they could have a real dialogue, listen to one another and respond immediately.

The exact status of their relationship is left ambiguous for the audience. Do you have your own ideas about the couple’s history?

No, I still don’t know. Truth is a possibility – what the reality is doesn’t really matter so much. What matters here is that they are possibly a couple. The man does say, “We make a good couple, don’t we?” And as long as the café proprietor regards them as a couple, then in a sense their being a couple is true, regardless of whether they are in reality.

Should we then see other characters in the film – the newly-weds, the tourists, the old couple – as reflecting possibilities open to the woman and the man?

That would be your interpretation. But I didn’t think along those lines. What I had in mind was to have four generations, rather like the four seasons.

The tourist who gives the man advice is played by the renowned screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière. How did that come about?

We’ve had a good relationship for years – I just asked him to come along. I didn’t want that character’s lines to be delivered by an actor who’d have to learn them. I wanted someone who could take a quick look at the character, then make the role his own in a voice that sounded credible. And Jean-Claude, I felt, had enough wisdom and experience for that. It’s something I learned with Taste of Cherry: the old man I chose – totally by chance – for the end of that film was a gift. He hardly looked at the lines, but knew instinctively what to say.

Did making ‘Certified Copy’ in Italy, with a bigger budget and bigger crew than usual, change your ideas about filming in the future?

I’m tempted to repeat Juliette’s answer when she won the Oscar for The English Patient and was asked by a French journalist, “Now you’re recognised in Hollywood, are you going to go and work there?” She said, “No, I want to work with Abbas Kiarostami.” I quote her not out of personal vanity, but because that exactly mirrors my attitude: I want to work with Abbas Kiarostami, back in Iran. And I hope to start shooting in September.

See also

10: one of Sight & Sound’s 30 key films of the 2000s (February 2010)

Tickets reviewed by Roger Clarke (December 2005)

Saraband (Bergman) reviewed by Jonathan Romney (October 2005)

Five reviewed by Jonathan Romney (June 2005)

Debrief encounter: Nick James on Richard Linklater’s Before Sunset (August 2004)

Drive, he said: Geoff Andrew considers 10 as among Kiarostami’s richest works (October 2002)

A little learning: Peter Matthews champions Kiarostami’s Homework (June 2002)

Faithless (Ulmann) reviewed by Philip Strick (February 2001)