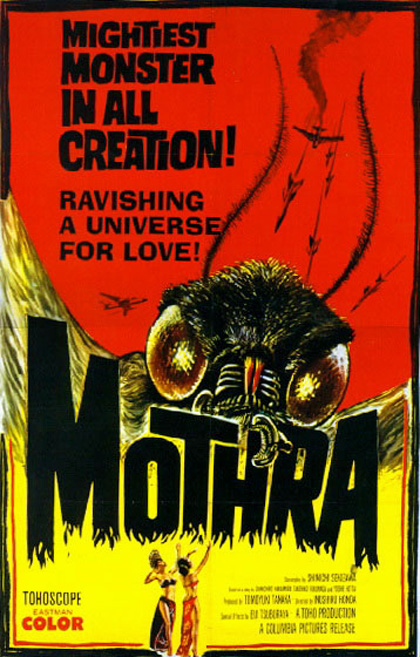

Lost and found: Mothra

Foot-high singers and a giant godlike moth made pioneering Japanese monster movie Mothra too wonderfully weird for America, says Kim Newman

Directed by Honda Ishirô for Japan’s Toho Studios in 1961, Mothra (Mosura) is one of those movies that when you describe it to people who’ve never heard of it, they think you’re making it up. Here’s the plot: when shipwreck survivors report that there are natives living on a supposedly uninhabited Pacific island used as a test site for atomic and hydrogen bombs by the nation of Roliscia, a joint Japanese-Roliscian expedition investigates, only to find a pair of foot-high twin girls who sing in unison. Roliscian entrepreneur Clark Nelson (Jerry Ito) is prevented by Japanese scientist Dr Chûjô (Koizumi Hiroshi) and comedy newspaperman ‘Snapping Turtle’ Fukuda (Frankie Sakai) from taking the ‘fairies’ away, but later returns and massacres the normal-sized locals in order to abduct the little beauties and force them to perform in a nightclub act. Their melodic song (‘Mosura-ya!’) impresses Tokyo crowds but is seemingly carried to the island by tribal dancers, its rhythms unearthing and then cracking open a giant egg, from which hatches a monumental grub. The larval form swims to Japan, causing chaos and destruction, wrecks the Tokyo Tower and spins a giant peanut-shaped cocoon in the ruin. Nelson smuggles the twins back to New Kirk City, capital of Roliscia, and the cocoon hatches out into – get this! – a moth the size of a jumbo jet, whose flapping wings create city-smashing hurricane winds. Mothra – for this is he/she/it (accounts vary) – flaps across the Pacific to Roliscia, intent only on rescuing the songstresses.

With Mothra, the Japanese giant monster movie (kaijû eiga) emerged from a cocoon of its own. The form began in 1954, when Toho producer Tanaka Tomoyuki had Honda direct Gojira, a blatant imitation of the American The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms that gained piquancy from references to Japan’s wartime (and, crucially, post-war) experience with American atomic weapons. (Gojira, Mothra and several other Japanese science-fiction films – plus Shindô Kaneto’s 1959 true-life drama Daigo Fukuryu-Maru – refer to the Fukuryu Maru or ‘Fortunate Dragon’ incident of 1954, in which the crew of a Japanese fishing boat were affected by fallout from the US hydrogen-bomb test on Bikini atoll.) Gojira was reworked for export in 1954 as Godzilla, King of Monsters! – with new footage featuring Raymond Burr – and founded a franchise. Toho brought its mutated dinosaur, revived in the modern world by bomb tests, back (or at least discovered another specimen) in Oda Motoyoshi’s Gojira no gyakushyu (1955), which was Americanised less elaborately as Gigantis the Fire Monster, but its next major monster movie was Honda’s Rodan (1956), which added vivid colour to the mix (the first Gojira films were in sober, sombre black and white) and a flying giant pterodactyl similarly concerned with wreaking havoc on the nuclear age.

Produced on a grand scale, the earliest Toho monster movies are still frank imitations of Hollywood. It’s no surprise that they were easily adapted into Americanised films like Godzilla, King of Monsters!, or that an American Godzilla could have been proposed long, long before Roland Emmerich got around to his 1998 version (which in shifting the locale from Tokyo to New York was essentially a covert remake of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms).

No one has ever seriously suggested an American remake of Mothra. If such a project ever became necessary, it’s hard to see where a would-be adaptor would even start. ‘Roliscia’ is supposed to represent both the US and the Soviet Union and function as a composite nuclear superpower, but it is plainly a caricature America, complete with cigar-chomping goons in gangster hats, skyscrapers rising from palm trees, crass showfolk (whose obvious antecedent can be found in King Kong), the murderous elimination of native peoples (the machine-gun massacre in the middle of a family-friendly film is still a shock) and a high-handed government who try to extend diplomatic immunity to the private-enterprise villain. Columbia put some money into Mothra and asked that the climax be more ‘international’ – ie that something other than Japanese property be under threat – but can hardly have been pleased that Toho took this as an excuse to visit divine retribution on America. (In the Japanese version, Mothra is more blatantly a deity and it takes the prayers of all faiths to appease it.) Most export cuts of Japanese monster movies trim anti-American bias (Emmerich even gleefully blames the bomb-testing French for his big iguana); with Mothra, the indictment of Roliscia – and, moreover, the refusal to take America seriously enough to use its real name – is so all-pervasive as to be an inescapable part of the package.

It’s not the politics, though, that are the chief block to a remake. It’s the sheer weirdness. The foot-high girls, played by Japanese singing duo the Peanuts (Ito Yûmi and Ito Emi), are among the most peculiar characters ever conceived for a commercial movie: they chirrup in unison, smile disarmingly throughout their ordeal, and are phlegmatic if sorrowful about all the innocent people their monster-god kills. In one hard-to-read moment, as a small fat boy in a red baseball cap (the first of many monster-befriending kids in Japanese cinema) removes an anti-telepathy cover on their birdcage, the girls seem to have been caught slipping their kimonos on after some mutual naked activity (though they might be covering their flesh-toned island dresses). That they exert great powers through singing is odd and eerie in itself, and the ‘Mosura-ya’ chant (with nonsense Japanese-Malay lyrics) is genuinely fascinating, sticking in the memory like a jingle for a long-discontinued product.

Mothra – yes, a giant moth – would be inconceivable for a ‘serious’ American movie. The creatures of The Deadly Mantis or Monster from Green Hell (giant wasps) could be seen as precedents, but are stiffs in comparison. More like a paper dragon in a parade, Mothra is simply lovely. In none of its forms does it even try to look ‘real’, which sets it against a whole tradition of Western special effects. Previous monsters, including King Kong and Godzilla, were cut down to size by planes and skyscrapers and tanks, but in another departure Mothra is allowed a happy ending. It flaps its wings, blows away all opposition and expects us to wave a cheery goodbye as it returns to its island with the girls.

What the papers said

“A ludicrously written, haphazardly executed monster picture from the Toho filmmakers of Japan. Though elaborately produced in Tohoscope, with a large cast and plenty of production fireworks, the post-dubbed film is too awkward in dramatic construction and crude in histrionic style to score at the box office. Exploitation measures are bound to lure thrill-seekers who flock indiscriminately to monster films, but even cinemutation buffs should wince at this one… At any moment, one expects Hope, Crosby and Lamour to pop into the picture… a pretty embarrassing effort on the part of Toho to duplicate a western screen staple.”

— Variety, 16 May, 1962

See also

Lost and found index

Joe Dante: serious mischief: Tom Charity looks back at Joe Dante’s four-decade-long anarchic streak (October 2010)

FrightFest Hallowe’en all-nighter 2010: Anton Bitel sticks out the witching hour with new films devoted to the return (or revenge) of the past (October 2010)

Kawamoto Kihachiro obituary: Jasper Sharp remembers the puppet maker and stop-motion animator (August 2010)

The last samurai: Alex Cox on the career of Shimura Takashi, Kurosawa’s ‘other favourite’ actor (June 2006)

The cage of reason: Kim Newman on Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow (January 2000)