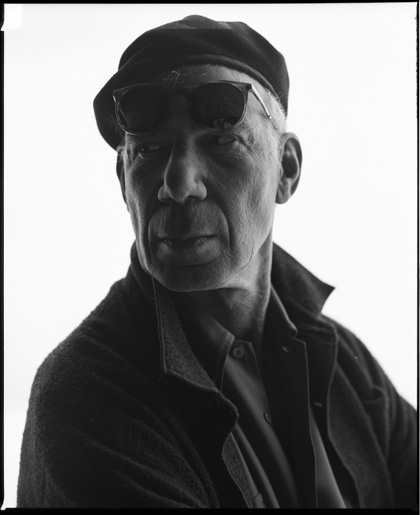

One for the road: Bob Rafelson and ‘Five Easy Pieces’

Forty years ago, ‘Five Easy Pieces’ made Jack Nicholson a star, and seemed to promise a new era of thoughtful American film-making. David Thomson looks back at a masterpiece, and talks to its director, Bob Rafelson

Five Easy Pieces was 40 years ago, and it seems like yesterday. If only it could be today. Think of the vitality in American film if the production model of BBS – the company formed by and named after Bob Rafelson, Bert Schneider and Steve Blauner – was still at work, and you could make a small movie about a young man’s failure to know who he is. Of course, I realise that’s not quite the same as protecting the prime blue forest and its people against energy imperialism; it’s not carrying out the next mission impossible; it’s not being a chatty toy cowboy who organises sweet assistance to the human world. But alas, not even in ‘the greatest country in the world’ (this phrase has all rights reserved, like Oscar) do all young Americans get such opportunities – though they may go a little crazy dreaming of them. No, most of the time young Americans are worried about who they are. This is the stuff of life. I know, because I am the father of two of them. And family is still the battleground.

So Bobby Dupea (Jack Nicholson) is an oil-rig worker in the hottest part of California, near Bakersfield. He acts like a redneck and a loudmouth, and he is with this girl, Rayette Dipesto (Karen Black), you know he can’t stand. How do you know? Well, he hounds after other women and takes them standing up in the living room in explosive sex scenes (thank you Sally Struthers – bravest thing you ever did), but you also know from a Bob Rafelson two-shot where Bobby and Rayette are side by side and the mixture of lust and loathing (sauced by absurdism) is the very essence of the young Nicholson – the new anti-hero. Because Bobby is too lazy or too afraid or too weak to simply tell the girl that it needs to be over. So the neglected truth is gathering in his soul like sourness in wine.

Then one day Bobby puts on a tie and a jacket, he combs his vanishing hair (the film makes sly jokes about that) and goes to a sound studio in LA where Partita (the sublime Lois Smith) is ruining her own recording by humming along with the Beethoven. She is his sister and she tells him their father is sick. So Bobby decides to go back to Washington state to visit, and it is his weakness that he can’t leave Rayette behind, though he knows she’ll ruin the trip. So they take to the road – and it is the road that really speaks to Bobby. We know that already from the scene where, caught in a traffic jam on the freeway, he quits his car, climbs on an open truck and starts to play the piano tethered there. Then the truck exits on a slip road with Bobby hammering away at his out-of-tune concerto.

Just a year earlier, 1969, the road had been Easy Rider. Bob Rafelson was an uncredited producer on that, as well as one of the gang who got the unruly picture edited. Then in his mid thirties, he’d had a mixed-up life. He was born in New York City, the son of a man who produced felt for hat-making. One relative was Samson Raphaelson, Lubitsch’s best screenwriter (The Shop Around the Corner, to name but one). “Samson took an interest in my work,” Rafelson remembers. “If he liked a picture, then I was his favourite nephew. But if he didn’t like it, I was a distant cousin! The film he liked the most, if you can believe it, was Head!” – the first feature Bob directed, a 1968 vehicle for the Monkees.

“My mother was an alcoholic,” Rafelson says, “and I would sit at the dining table and my father didn’t know how to talk to me. The result was that I was off in a rodeo at 14, and soon after that I’d been halfway round the world.” Bob shifted the name to Rafelson (more American) and he liked to be called ‘Curly’. He was a rebel ahead of the 60s – an adventurer with an aggressive edge, a traveller and an explorer. (Mountains of the Moon, his 1989 account of Burton and Speke’s 19th-century search for the source of the Nile, is one of the best films about why people go to wild and crazy places.)

But Easy Rider (you may say) is a pretty awful, loopy picture – no matter that it made a fortune – in which the road is a playground for addled children. Whereas the road in Five Easy Pieces (and in its brilliant script by Carole Eastman) is the hint of escape, a way back to the past and the measure of Bobby’s rootlessness. So in the last scene, distant and drawn out like the close to The Passenger, Bobby dumps Rayette and hitches a ride on a truck going to Alaska, without even a jacket to wear. No one knows if he ever came back, but he had tried being Robert Eroica Dupea in Washington and it didn’t work any better than his season as Bobby near Bakersfield. So it’s the story of a man who can’t settle or find himself, in which the road is not simply a means of discovery, but the desperate evasion for someone who can’t grow up.

“I had done some writing of my own in the 60s, some scripts, and a lot of it was based on friends I had had at college and afterwards,” Rafelson recalls. “Some of these people were dead already – so I was writing about self-destruction. But I didn’t like the scripts and I showed one of them to Carole and asked her to do what she could with it. Well, the result was Five Easy Pieces, and the only scene of mine she kept was the one in the diner.”

It had always been intended for Nicholson. Rafelson met the actor at a strange film society in Hollywood. “You paid $10 membership and they showed foreign films and Cassavetes. And I noticed this guy sitting in front of me. If he saw anything he liked, he’d jump up and shout ‘Yeah!’ And I was doing the same. So we became friends. He was out of work at that time and he was even considering turning it in as an actor. But I asked him to write Head with me – we did it together in Harry Dean Stanton’s basement, with a psychedelic assist. And then when we did Easy Rider and Rip Torn had his fight with Dennis [Hopper] and Peter [Fonda] – Jack got that part. Everyone thought he would be a calming influence on Dennis and Peter! I was very resentful because I had planned on discovering Jack myself.”

In 1970 Jack was about to be the great new hero. You could feel his star shining brighter with every film. Jake Gittes (Chinatown) and Randall McMurphy (One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest) were only a few years away. But Bobby Dupea is a cop-out, an immature energy force without self-knowledge. Every now and then you see how close he is to a breakdown.

Fractured tenderness

Two years later, the same sort of problem was the centre of Rafelson’s follow-up, The King of Marvin Gardens, which may be an even better film. This is the story of the Staebler brothers. David is hunched, depressive and still locked into home in Philadelphia; his only escape is the radio studio where he weaves nocturnal fictions from his drab facts. But he has a wild brother, Jason, the manic that depression can’t lose, the guy with immense, implausible schemes. They have been apart, but they are reunited in an insane venture that turns into everyday tragedy. It’s a key part of Rafelson’s approach that the actors who play David and Jason – Nicholson and Bruce Dern – might easily have swapped roles.

The King of Marvin Gardens

If you regard these fraternal films as parts of the same family of work, you may see the subtle scrutiny of American creativity that intrigued Rafelson, and the feeling for fractured tenderness. David Staebler is a magician in the radio studio, and a chump outside it. Bobby Dupea is trying to be a common man, but he might have been a concert pianist. The lack of resolution has ambushed his life and left him a chronic outsider. Up in the green country of Washington state, he meets (and goes to bed with) his brother’s fiancée Catherine (Susan Anspach), who tells him he has so little self-respect that he cannot be loved. It’s the one chance he has of ‘redemption’, but Bobby has already killed that big dream with his stress on running away when things go bad.

Five Easy Pieces is an important extension of the myth of the road in American culture. What makes it memorable is the concurrent feeling that Bobby is an attractive self-destructive – the trip to Alaska is the deadest of closed ends, yet he has the charm, the wit and the endearing rebellious smile that was Nicholson in 1970. The famous scene in the diner where Bobby gives the waitress instructions in how to deliver a side order of toast is so modest yet so far-reaching – somehow it embodies every libertarian urging against dead order in American cinema of that time.

Moreover, the film was a business coup as well. Rafelson had several anti-business instincts: he got fired from the Robert Redford vehicle Brubaker after he turned a desk over in an executive’s lap. But he had also had the iconoclastic demon in him that created the Monkees pop group out of nothing, and then put them in Head. After that, with his friends Bert Schneider and Steve Blauner, he put together BBS, a company to make independent films at around a million dollars apiece.

Five Easy Pieces went as high as $1.6 million, but it had US rentals of $8.9 million and it seemed to point to a future. The next year they produced Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show – another hit and another sad, naturalistic treatment of the flaws in young people (as opposed to a fatuous glamorising of their discontent). Both films were nominated for Best Picture Oscars. But the model crumbled. BBS made Drive, He Said (Nicholson’s directing debut) and Henry Jaglom’s A Safe Place, and those films lost money.

What happened to BBS? Why did it fold? This is what Rafelson has to say: “The immediate answer was that someone had to go around collecting rents from our building on North La Brea. When they said it was my turn, I said, ‘No, I don’t want to do that.’ The larger answer was that I was bored with all the business. We had another film planned, a picture by Jim McBride set in the 18th century. And he wanted to use real buildings which were too small for a camera. So his producer said he couldn’t and the picture fell through. I was very upset. But I wanted to make my own pictures. And Bert was moving towards radical politics. He wanted to do Hearts and Minds [the 1974 documentary about the Vietnam war]. So it ended – and we were all relieved at the time.”

Looking back on it now, BBS seems like a dreadful loss, but ordinary ambitions and success usually change that kind of idealism. Bob Rafelson is 77 now. He lives in Aspen, Colorado, not entirely retired, but not too interested in going back to Los Angeles. When I talked to him, he was recovering from spinal surgery. We have been friends for over 30 years and I think that Five Easy Pieces and Marvin Gardens are crucial achievements in the silver age of the early 1970s. Rafelson never quite regained the originality of those early films, though he is eager to have it remembered that he helped produce Jean Eustache’s La Maman et la putain (The Mother and the Whore, 1973). That’s the ethos of that film society in Hollywood, and the urge to exceed American norms. It was in the same spirit that Rafelson grew up with Nicholson certain that he was in the privileged position of working with “maybe the greatest actor of our time”. “Jack can be disgruntled and melancholic,” he adds, “but he is so smart. And you can’t beat that.”

I admit to friendship with Rafelson, but I loved these two films before I met him. Their treatment of family cannot be overstressed. So much of American film isolates and glorifies individualism. Take John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards in The Searchers. Some Fordians praise Ethan for finding it in himself to forgive his niece Debbie for being married to a Comanche. So the uncle brings the girl home, and straightaway quits – going back into the wilderness, the door shutting behind him. When what he needs to do is to try to talk to Debbie. Bobby cannot talk to his father, and it is an agony, but there is no shirking the attempt or the essential American loneliness it contains.

See also

He stands alone: Martine Pierquin on Jean Eustache (online, November 2009)

Thunder roads: Michael Atkinson on gangsters, the Great Depression and the American nomad soul (August 2009)

Giant steps: David Thomson on the maverick cinema of 1970s Hollywood (September 2006)

Don’t fence me in: what exactly is Jack Nicholson’s appeal, wonders Danny Leigh? (May 2003)