Primary navigation

An epic biopic of legendary terrorist Carlos marks a change of pace for Olivier Assayas. By David Thompson

Olivier Assayas’ exhilarating, ambitious film about the international terrorist Carlos ‘The Jackal’ is an event in more ways than one. It was financed by Canal Plus as a three-part movie for television running five-and-a-half hours, with a theatrical version half that length. Its protagonist, imprisoned in France for the murder of two French policemen and their informant, campaigned (unsuccessfully) against the film. The long version was almost in and then out of competition at this year’s Cannes Festival, because of restrictions placed on films financed by TV which only apply to French productions. Assayas is now reconciled to these difficulties, and is content that the superior five-and-a-half-hour cut is receiving some theatrical exposure worldwide.

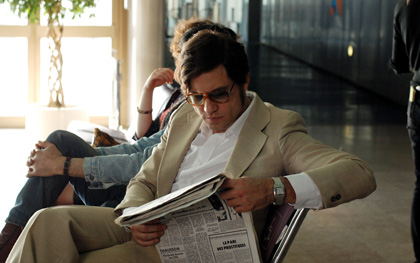

The film follows Carlos – brilliantly incarnated by Edgar Ramirez, who like Carlos is Venezuelan-born – from his attempt to assassinate a British Zionist in London in 1974 to his arrest in 1994 in Khartoum, exploring en route his key role in the raid on an OPEC conference in Vienna and his involvement with German terrorists. Assayas has previously worked mainly in the realm of fiction – his last film Summer Hours (L’heure d’été, 2008) being his most commercially successful to date, with the US remake rights acquired by Tom Hanks. Here, however, he uses globe-trotting docudrama not just to deliver Bourne-like thrills and spills, but to uncover the complexities of a terrorist world that is inextricable from the interests of state leaders and secret-service agents.

David Thompson: By chance, we’re speaking on 11 September, a date that brought a new meaning to the idea of terrorism. But here you’re dealing with another era entirely. As Carlos says himself, “I am a soldier, not a martyr.”

Olivier Assayas: Historically the first [terrorist] martyrs who were willing to sacrifice themselves for their cause were the Japanese kamikazes in the early 70s, who were considered freaks. The revolutionaries were militant atheists – Marxists – so the idea of martyrdom was completely alien to Carlos and the guys around him. To be willing to risk your life in a dangerous operation is something else.

Unlike most of your films, this project wasn’t your idea to begin with.

No, but I most definitely gave it its shape from the start. What came to me were four pages, a rough narrative about how Carlos was arrested in the Sudan by the French. I wasn’t attracted to this except for the very idea of using Carlos as a character in a film. So this is what I told the producer, Daniel Leconte, and he sent me all the research done by a journalist specialising in French-African affairs, Stephen Smith. Reading that was fascinating, because I had thought Carlos was some kind of secret agent, but there was more available than I had imagined in terms of the operations and his involvement in the geopolitics of his time. I experienced the same kind of curiosity and excitement as if I had been watching an action film or reading a thriller. So I said to Daniel that for me the right angle was to tell Carlos’ story from his point of view. There was something exciting and unique about this story, and it opened an interesting perspective on modern history, and how to deal with it in modern cinema.

How did the eventual shape of the film come about?

This was meant to be for TV from the start, a 90-minute film for Canal Plus. So I told Daniel that 90 minutes wouldn’t work – we needed the full arc of the character to make sense of his story and his times. I said it couldn’t be less than two movies – twice 90 minutes. He was a bit reluctant, but we met with the guys from Canal Plus, in particular the head of fiction Fabrice de la Patellière. I explained my position and a week later they said, “OK, we’re fine with two parts.”

At that point I started working on the script. There was a screenwriter who was part of the deal – a novelist, Dan Franck – so I discussed the framework with him. I had the beginning and the end. I knew I wanted to start with the death of Mohamed Boudia, as that was the beginning of Carlos – it led to his meeting with Wadie Haddad, because he wanted to take over as the leader of the European network of the PFLP [Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine]. And to me the ending was Carlos’ arrest.

But after one meeting with Dan, it was obvious that two movies were not enough! I hadn’t realised the complexity of the whole Vienna episode. I knew it was one of many operations, but as I researched it I saw it was monumental. It’s very well documented, it’s extremely exciting and if you start describing it, you have to go all the way. I gave Canal Plus a new outline, and after further negotiations we managed to get the three parts.

Did the examples of recent two-part films such as ‘Che’ and ‘Mesrine’ help convince them of your need for all this screen time?Yes, because this was more like a big-scale, international independent film, with a future in cinemas. So I knew I had to shoot in 35mm, use the CinemaScope format and figure out how to deal with two versions – a maximum of six hours for television, and much less for non-specialised cinemas.

There’s a lot lost in the theatrical version, but you do retain much of the personal detail about Carlos, in particular his aggressive sexuality.When you start researching the story of Carlos, girlfriends pop up everywhere! One has written a book about their relationship, another hid weapons, there’s Magdalena Kopp, who’s a central character, then the Jordanian girlfriend he’s filmed with in Sudan… Every specific moment in the history of Carlos has the attached girlfriend. It’s obviously part of his story, his myth, his way of operating. We have to deal with Carlos’ hedonism, which set him apart from the puritans in the Left of that time. He wasn’t a hippie either – he was an old-world hedonist, with a very bourgeois style of dressing, staying at the best hotels, smoking Castro’s cigars. And that was not considered cool at the time – it was not connected to the revolution.

This is what fascinates and attracts the characters around him – all the memoirs are obsessed with this side of him, and the care he took over his body and appearance. He was an actor, a showman, and when he puts on the OPEC operation, he dons a mask – in this case Che Guevara. And of course all of this makes for a stronger cinematic character.

The shorter version also skips over most of the 1980s, when you see that terrorists were as much in league with the communist countries as they were with the Arab cause.

The shorter version also skips over most of the 1980s, when you see that terrorists were as much in league with the communist countries as they were with the Arab cause.

So much of the European leftism of the 70s and 80s is defined by the Cold War. Carlos is a Cold War warrior. The German leftists get dragged into a secret-service world, which is not supposed to be a visible part of their activities. And it’s what stupefies [German terrorist Hans-Joachim] Klein, because Carlos is now ?ying around in private jets and meeting heads of state. And no one knew that this was happening at the time. People could not imagine the involvement at the highest level in terrorist activities – that these guys were supported by the Stasi as well as the leaders of the Middle East, that the President of Yemen would send them his private plane.

How did you go about casting Carlos? Were you encouraged to find a well-known actor?It’s not that I wouldn’t have been happy to use a known actor, but to have a believable Carlos I needed a Latin-American in his early thirties, who was the same build as Carlos, and who was ?uent in English, Spanish and French. So that narrowed down the candidates! As to the choice of Edgar Ramirez, well, a computer could have made it – he fits all the categories. The miracle is that he happened to be incredible – he’s a great actor, and he’s possibly the driving force of this film. All the other actors were mainly Lebanese or German, so the producers didn’t mind who else I cast. They gave me total freedom.

Before shooting, you told me you hoped to film in as many of the authentic locations as possible.I very much wanted to shoot in Yemen and also Sudan, which did not seem out of reach at the time. I went there to see locations, as we did in Syria, and it was very useful to have a sense of the neighbourhoods where Carlos lived. We were able to shoot a few exteriors in Syria with a reduced crew. Damascus was always going to be impossible, as the Syrians were not going to be happy with what the film says about their activities.

Yemen looked accessible, but the French producer called it off at a week’s notice. Maybe he was right that it would have been dangerous. Khartoum was closed to us after [Sudanese] President Omar al-Bashir was indicted for war crimes in Darfur, and was clearly not interested in doing any favours to Westerners. So those countries had to be filmed in close-up in Lebanon.

Did you have any direct sources helping you?There was Hans-Joachim Klein, who lives in France. The producer Daniel Leconte knows him. We met him twice. He helped us to recreate [the] OPEC [operation] in terms of the set and the logistics, so he acted as a kind of technical advisor. Also we met Anis Naccache, or ‘Khalid’, but he’s still active as a secret agent, so he didn’t want to tell us much.

And how about Carlos himself?

And how about Carlos himself?

Carlos has been lying about everything from the start. My opinion – and it’s just my opinion – is that he only told the truth once, when he gave the interview to Assem al-Joundi, which we staged in the film. It feels genuine, though now Carlos says it’s complete bullshit, because he talks about some operations which he no longer admits to. So why add another layer of confusion? Plus the Carlos who’s in jail now is very far from the 23-year-old who visited Wadie Haddad in Beirut.

The Canal Plus lawyers were against making any connection. During the shoot and the editing, Carlos tried to get hold of the screenplay, because he wanted his say, which was obviously legally impossible. If you’re trying to present modern history and allow all the protagonists to have a say, there’s no way you can do it. But it put me under pressure to tone down this and that, and be very careful of any situation not proven or documented, so in a way he got what he wanted.

He gave interviews based on the screenplay, criticising that it said he wore a gold chain, saying that he never wore one in his life, that he never smoked cigarettes, only cigars, these kind of things. Which means, I guess, that ultimately the rest must be true! His main point was about who commissioned the OPEC operation, as on the internet he has incriminated Gaddafi, saying that it was entirely Libyan-backed. But what are his reasons for this? He’s the only person to say this – everyone else says it was an Iraqi operation. Ultimately I softened the position in the film, as it was likely Gaddafi was involved, but he was certainly not the sole person responsible. Saddam Hussein had a solid reason for wanting an increase in the price of oil, and the political links between Libya and Iraq were very strong.

Putting aside the scale of the film, this is the first time you’ve tackled a true story.Carlos was exciting because it was a whole new world for me. I was extremely lucky to bump into this story, because to talk about the politics of the 70s, it’s the best story of that time. You can always talk about the terrorist cells then, but with Carlos it’s so globalised – he’s so involved in the geopolitics of that time – that he’s really at the centre of what’s going on.

Other films on terrorism seem to focus on the group in question and barely look outside their lives.Yes, Wakamatsu’s United Red Army is a story about the Japanese, just as The Baader Meinhof Complex is about Germany and Bellocchio’s Good Morning, Night about Italy. As if somehow the terrorism of those times was a national affair, when it was not. And Carlos reveals that.

The whole idea of creating actual facts in cinema, it’s very stimulating, very inspiring. It’s like the historical plays of Shakespeare, where events are happening everywhere at the same time. It’s a genre, but to me this is not a political film, but a film about politics, and what makes modern politics – which is complexity and international connections. So that when the car bomb goes off in rue Marbeuf [in Paris], it’s important to understand that the fake passports were supplied by the Stasi in East Berlin, and that the car bringing the bomb is picked up in Ljubljana. And you need five hours to make those connections between Carlos and the Syrians and the Germans – and why the bomb kills Frenchmen in front of the offices of an Iraqi newspaper.

Most people don’t have the time to deal with these complexities. But then you have Carlos, who’s interesting, sexy – there’s the human element that he wants to get his girlfriend out of jail. So you can tell the story in cinematic terms.

The full version of ‘Carlos’ screens at the London Film Festival on 16 October. Both versions are released on 22 October, and are reviewed in the November 2010 issue of Sight & Sound

Four Lions reviewed by Ben Walters (June 2010)

Italian cinema: maestros and mobsters: Nick Hasted on a new generation of filmmakers finding ways to tell Italy’s story after 30 years of cinematic nostalgia, endemic corruption and the deadening hand of Silvio Berlusconi (May 2010)

United Red Army: one of Sight & Sound’s 30 key films of the 2000s (February 2010)

Radical chic: Andrea Dittgen on The Baader Meinhof Complex (December 2008)

Paradise Now reviewed by Ali Jafaar (May 2006)

Team American World Police reviewed by Leslie Felperin (January 2005)

Fahrenheit 9/11 reviewed by Mark Cousins (September 2004)

Our friends from Turin: David Forgacs on The Best of Youth, a six-hour television drama about Italy’s ’68 generation (July 2004)

Stop making sense: David Thompson on Olivier Assayas’s Demonlover, plus an interview (May 2004)

One Day in September reviewed by Peter Matthews (June 2000)

Late August, Early September reviewed by Chris Darke (September 1999)