Primary navigation

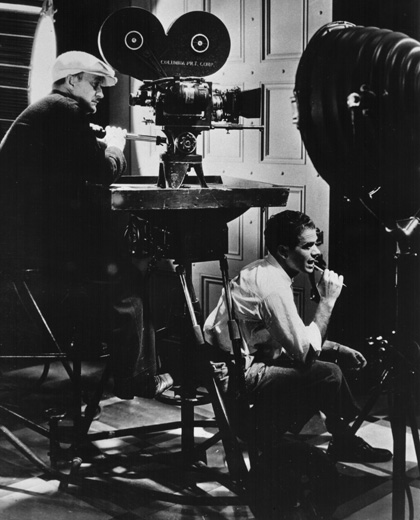

Joseph Walker (left) and Frank Capra working together in the early 1930s (The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences/Columbia Pictures)

Celebrated each Christmas for the ‘Capracorn’ of It’s a Wonderful Life, Frank Capra deserves reappraisal as a director in the light of the restoration of his 1920s silents and his luminous talkies of the early 1930s. By Joseph McBride

There’s a school of Frank Capra criticism that argues that the great American director did his best work before he entered his socially conscious phase in the Depression era – before he found a way to “say something”, as he put it in his largely fictitious 1971 autobiography, The Name Above the Title. I don’t belong to that school, because I believe Capra only reached his artistic maturity when he began working in the early 1930s with screenwriters Jo Swerling and Robert Riskin, who provided him with that elusive something to say. Riskin especially brought to Capra a more sophisticated sociopolitical viewpoint, a liberal sense of empathy and political satire that the director may not have fully shared, but gave a greater depth and emotion to his work.

The counter-argument to this view of Capra’s artistic growth has some merit – Alistair Cooke summarised it in his comment on the 1937 white elephant Lost Horizon: “Capra’s is a great talent all right, but I have the uneasy feeling he’s on his way out. He’s starting to make movies about themes instead of about people.” But given the passion on both sides of the debate, it’s surprising how little serious critical attention has been paid to Capra’s early work – the highly eclectic body of films he made before It Happened One Night made him a celebrity director in 1934 and changed his life forever, not entirely for the better. The upcoming Capra season at London’s National Film Theatre provides such an opportunity to re-examine Capra’s beginnings, as did the 2009 early-Capra retrospective as part of Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, in which I participated.

A major reason that early Capra has been neglected by audiences and critics has been the sheer difficulty of seeing much of it. A US distributor, Kit Parker Films, circulated Capra silents and early sound films on 16mm decades ago, but only a few of his features for Columbia Pictures from the 1920s and early 30s have been made available on VHS or DVD. On the other hand, many of the films he made with silent comedian Harry Langdon (first as writer and then as director) have recently shown up on DVD. Most of Capra’s early Columbia films long existed in bastardised prints of indifferent quality, often preserved only because of the efforts of European collectors and archives. Joseph Walker, Capra’s indispensable cinematographer, told me that Columbia president Harry Cohn was too cheap to take good care of the studio vaults in Capra’s heyday.

Capra (seated) working for Columbia in 1927 (Columbia Pictures)

Sony Pictures, the successor to Columbia, has recently undertaken a major restoration project of its invaluable early-Capra legacy. Sony’s restoration wizards Grover Crisp and Rita Belda have performed dedicated and resourceful work in scouring the world for the best existing sources of footage. In the process they have taken special pains to seek out the original wording and graphic style of the silent films’ intertitles, which were often translated very loosely by foreign distributors. The serendipitous rediscovery of Capra’s collection of films at his former southern California ranch in Fallbrook (which he later donated to his alma mater, the California Institute of Technology) yielded badly decayed 35mm nitrate prints made for Capra by Columbia before he left the studio in 1939. But from those prints and from paper records, original intertitles of the silent films have been recreated.

The results, as seen in Bologna, are often revelatory. This highly diverse early period – in which Capra displayed a remarkable versatility as he worked in various genres at breakneck speed (he had seven features released in 1928 alone) while struggling to discover his true artistic personality – can now be viewed more coherently. Nearly pristine (or at least sharper) prints of the silents and early sound films, some indisputably among Capra’s best work, reveal their virtues more fully.

The gradual development of Capra’s professionalism and expertise can be tracked in watching his work as a director from 1921 onwards (his previous directorial efforts, Screen Snapshots documentaries on Hollywood in 1920, are lost). His greatest strength as a director may have been his ability to discover and bring out the best in his actors. The lively tempo and physical energy of his pictures also owed much to his personal vitality and his brio as a showman. As a pictorial stylist, however, Capra leaned heavily on Joseph Walker, who was mostly responsible for the sensual texture of the Columbia films. Capra’s work was not particularly distinguished visually before he began working with Walker in 1927, and it showed a sharp decline in that department (and every other) after they stopped working together in 1946. But the spectacular beauty of The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933) – which Capra told soundman Edward Bernds in the late 1930s was his favourite of all his films (“I know it didn’t make money, but it has more real movie in it than any other I did”) – and the luminous sheen Walker brought to such films as The Miracle Woman (1931), Platinum Blonde (1931), Forbidden (1932) and American Madness (1932) are even more apparent in Columbia’s restorations.

Toshia Mori, Barbara Stanwyck and Nils Asther in The Bitter Tea of General Yen (Columbia Pictures)

American Madness, a Riskin original about a progressive bank president (Walter Huston) who prevents a run on his bank, is more timely than ever in the light of the recent collapse of the US economic system; this incisive, brilliantly directed film marks the start of Capra’s intense engagement with Depression-era social criticism. The sparkling wit of Platinum Blonde – in which Riskin (inadequately credited only for the “dialogue”) and Swerling (credited with the “adaptation”) set the tone for Capra’s subsequent socially conscious romantic comedies – has found the champions it deserves. And The Miracle Woman (adapted by Swerling from a play by Riskin and John Meehan) was aptly hailed by Richard Koszarski in 1971 as “one of those wonderful films of the early thirties which attacked all the rotten, sacred things the studios could think of.”

Sam Hardy and Stanwyck in The Miracle Woman (Columbia Pictures)

These films seem even fresher and more compelling now than when Capra’s work was undergoing its first major wave of rediscovery in the early 1970s thanks to The Name Above the Title. The astonishing Miracle Woman not only does not show the signs of compromise Capra claimed to find in it but – with its scathing satire of a phony evangelist exploiting the thoughtless masses – would seem radically unfilmable in the reactionary political climate of today’s America. Barbara Stanwyck is as sensational here as she is in her other early starring roles for Capra, from her moving breakthrough as a spunky, tender-hearted prostitute in Ladies of Leisure (1930) through her majestic role as a missionary in love with a Chinese general in The Bitter Tea of General Yen, a richly complex study of racism that is also Capra’s most pictorially sumptuous film.

Ralph Bellamy and Stanwyck in Forbidden (Columbia Pictures)

The intensity and lucidity of their work together in five films (also including the bizarre Forbidden, a Stanwyck tour de force of diverse acting styles, and their later flawed classic Meet John Doe) is one of the most fertile creative teamings of director and actress in cinema history. (Sony has been planning a Capra-Stanwyck boxed set.) Capra was in love with Stanwyck in the early 30s and expresses the futility of their union through his romantically fatalistic, suicidal surrogate General Yen (Nils Asther) in the deeply personal Bitter Tea. He also provides a covert autobiographical portrait of his four most important romantic relationships (with Stanwyck; his first wife, Helen Howell; his second wife, Lucille Warner Reyburn; and his college girlfriend, Isabelle Daniels Griffis) in the seemingly formulaic mishmash of genres that superficially characterises the mesmerisingly peculiar Forbidden.

The opportunity to re-evaluate Capra’s early work can yield fresh insights into films that have been unfairly neglected, whether because they lack enduring stars or because they may seem somewhat formulaic as genre entries, or threadbare in production values. There are also films – such as The Way of the Strong (1928), a moody gangster movie about “the world’s ugliest man” – whose sheer quirkiness and seemingly uncharacteristic themes can now be seen as revealing the darker recesses of Capra’s personality. In this obsessively downbeat film, the director brings a convincing intensity to the doomed romance between hulking “Handsome” Williams (Mitchell Lewis) and a blind violinist (Alice Day, from Capra’s Sennett films).

Capra’s lifelong insecurities involving women and sexuality (which, in our interviews for my 1992 biography Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, he attributed, perhaps partly metaphorically, to a wound suffered during a botched circumcision) were expressed onscreen through such surrogates as the infantile Harry Langdon, the grotesquely malformed “Handsome” and the elegant and sensitive yet hapless General Yen, who kills himself when he realises that the sympathetic white missionary woman he loves (Stanwyck) can’t quite suppress an instinctive revulsion toward his race.

Joe Cook in Rain or Shine (Columbia Pictures)

For me, the major rediscovery at Bologna (and subsequently at the Capra festival held by the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, California) was Rain or Shine (1930), one of Capra’s least-celebrated early talkies. This circus picture, starring the forgotten but brilliant comedian Joe Cook, is a cockeyed masterpiece, a strangely exhilarating mélange of surreal verbal comedy and semidocumentary realism (there’s a stunning big-top fire sequence, and the communal spirit of the circus troupe feels authentically brought to life). Cook’s fast-paced banter and verbal jousting with sidekicks and stooges often gives the film the incongruous feeling of a Samuel Beckett play (the bowler hats worn by Cook’s Smiley Johnson and others, and the general atmosphere of trampish desperation, contribute to that quality). The film’s blend of Depression-era grimness and dauntless can-do spirit gives it political overtones as strong as anything in Capra’s work. Although the film predates the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Smiley seems a proto-FDR figure in his indefatigable optimism and ability to rally the spirits of his beleaguered troupe in the worst of circumstances. In a moment of crisis Clarence Muse, one of Capra’s favourite character actors, even plays ‘Happy Days Are Here Again’ – which would become FDR’s theme song – on his calliope.

An even more obscure work about show business – and another minor gem with major virtues – is The Matinee Idol, a 1928 Capra silent missing until its rediscovery in the late 1990s, misfiled under another title at the Cinémathèque Française. British actress Bessie Love gives a spirited and engaging performance as Ginger Bolivar, the dauntless head of a small and rather pathetic theatrical tent show putting on an unintentionally ludicrous Civil War play. Slumming Broadway star Don Wilson (Johnnie Walker, also the cocky leading man of Capra’s engaging, ultra-cheap-looking 1928 boxing comedy So This Is Love) finds Ginger appealing and goes along with the gag of importing her troupe to the New York stage. In depicting the collision between rustic sincerity and big-city cynicism, the film anticipates the themes of the Capra masterworks Mr Deeds Goes to Town (1936) and Mr Smith Goes to Washington (1939). When Don realises how cruelly he and his cronies have hurt the feelings of Ginger and her fellow performers, he experiences a change of heart that turns him into a mensch. He’s the male equivalent of the wisecracking but secretly tender and emotionally vulnerable characters later played by Capra’s favourite actress, Jean Arthur, in her films opposite Gary Cooper and James Stewart.

Capra (right) directing Bessie Love and Johnnie Walker in The Matinee Idol (Columbia Pictures)

Some of Capra’s voluminous silent work is still missing, including an early feature, The Pulse of Life (1920), that he wrote and may have acted in; the Screen Snapshots Hollywood documentary shorts on which he served as an assistant director, editor and probably director; most of the Plum Center comedies, a genial slapstick series shot in northern California on which he worked as a gag man and in other capacities; and many of the 25 Mack Sennett comedy shorts he wrote (his often wildly ingenious scripts exist in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences’ Margaret Herrick Library and Capra’s papers at Wesleyan University). The period in Capra’s career before he became a director in the early 1920s was the hardest aspect of his life for me to research, because he lied so strenuously in his autobiography in an effort to cover up his first several years in the business. Capra egotistically preferred his readers to believe that, with no previous experience, he had simply become a director on the surprisingly sophisticated arthouse short Fulta Fisher’s Boarding House in 1921 after bluffing his way into the job with an unsuspecting San Francisco producer. In fact, his gradual rise through the ranks in a series of jobs – ranging from an extra role in John Ford’s The Outcasts of Poker Flat (1919) and “cleaning up the horseshit” at the Christie Film Company in Hollywood, to working as an assistant director and a laboratory technician and directing documentary shorts – makes a more genuinely inspiring saga of unrelenting ambition and drive.

Probably the most significant rediscovery in the early Capra canon is, unfortunately, not scheduled to be part of the NFT retrospective, although it has been shown at Bologna and earlier by the American Film Institute in Silver Spring, Maryland. The silent documentary La visita dell’incrociatore italiano Libia a San Francisco, Calif., 6-29 Novembre 1921 (The Visit of the Italian Cruiser Libia to San Francisco, Calif., November 6-29, 1921) was shot after Fulta but actually preceded it to the screen, playing briefly in a San Francisco cinema in December 1921. While writing my biography of Capra, I discovered the story of the film’s making in his papers, but didn’t realise that the actual film still existed with a successor organisation to the group that made it, the Italia Virtus Club of San Francisco. Resurfacing in 2005, it was restored by the American Film Institute at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in Bologna and preserved by the US Library of Congress.

Somewhat rough-hewn but fairly professional-looking, this commissioned short is a lively, multifaceted portrait of the city’s Italian-American community welcoming the captain and crew of an Italian battleship that had become celebrated in the Great War. Capra gives himself a cameo, conferring with his Italian-language title writer (journalist Giulio DeMoro) while standing on a dock, smoking a cigar and affecting a Cecil B. DeMille-ish look in high boots. The scenes of the ship’s arrival in the bay are filled with visual energy, and the joyous, relaxed demeanour of the many and diverse ordinary faces captured by Capra’s camera are an early testimony to his amiable ability to serve as a surrogate audience for his onscreen performers. The film unfortunately bogs down for a lengthy, obligatory section showing seemingly every local worthy attending a welcoming dinner at the Fior d’Italia restaurant. Though lacking the polish Capra brought to Fulta, the documentary reveals an embryonic talent with a keen, affectionate eye for the humanity of what would later be known as Capra’s ‘common man’ protagonists. Hopefully some enterprisingly esoteric distributor will pick up this public-domain title for DVD distribution.

Although Capra’s artistic personality was not fully formed in the silent era, traces of what would become known later as ‘Capraesque’ film-making – that uneasy, hard-to-define mixture of populism and sentiment – are most clearly visible in his 1928 comedy-drama That Certain Thing, about a young couple (Viola Dana and Ralph Graves) who run a boxed-lunch company that conquers a corporate Goliath. But the most personal film Capra made in the 1920s may well have been The Younger Generation (1929), a part-talkie about a Jewish American (Ricardo Cortez) who tries to deny his ethnic heritage to become more fully assimilated – much as Capra tried to do with his Italian family background. (His earlier Italian-language documentary on the Libia, a celebration of his own cultural identity, is a notable exception in his life and work.) Through screenwriters Swerling and Riskin – and later Sidney Buchman (Mr Smith Goes to Washington) – Capra eventually found the voice for what would become known as his characteristic style of socially conscious comedy-drama conveying his ambivalent love of his adopted land, even if to most people today the word Capraesque connotes the escapist supernatural whimsy that competes uneasily with some acute social criticism in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

Robert Riskin (left) with Lady for a Day star May Robson (center) and Capra (Columbia Pictures)

Capra needed sound to reach his full potential as an artist, as did such other great directors as John Ford and Howard Hawks. His films revel in the sounds of American common speech and music – the voice of the crowd. He admitted that he found the coming of sound “an enormous step forward. I wasn’t at home in silent films. I thought it was very strange to stop and put a title on the screen and then come back to the action. It was a very contrived and very mechanical way of doing things. When I got to working with sound, I thought, my, what a wonderful tool has been added. I don’t think I could have gone very far in silent pictures – at least not so far as I did go with sound.”

The deeper question of whether Capra was a better film-maker before or after he learned to “say something” in the 1930s will remain a subject of debate among critics with differing ideas of cinema’s mission and potential. The complexity of the question is suggested by an exchange I had with Capra while helping him write his acceptance speech for the 1982 American Film Institute Life Achievement Award. Though in conversation he often struck me as virtually misanthropic, he proposed the following lines: “The art of Frank Capra is very, very simple: it’s the love of people. And add two simple ideals to this love of people – the freedom of each individual and the equal importance of each individual – and you have the formula upon which I’ve based all my films.” I suggested that “principle” would sound better than “formula”. Perhaps I was wrong to coax Capra into claiming that his sentimental humanism was more than a mere formula to him. But when you watch his best pictures, they seem to transcend formula to reveal life as it is actually lived; as François Truffaut put it, “I have often wept during the tragic moments of Capra’s comedies.”

What Capra himself vaguely felt was lacking in his pre-Swerling/Riskin work was a coherent social viewpoint. That fuzzy perspective helps account for a relative lack of emotional depth in most of his earlier films, despite their considerable virtues. If Capra’s technical facility is elaborately demonstrated in Submarine (1928) and Dirigible (1931), those remain macho action genre pieces without much directorial personality. The intermittent glimpses of aspects of Capra’s more compellingly personal concerns in the other early films are mostly recognisable only with the help of strenuous biographical research. But the enduringly successful artistic personality that Capra eventually discovered with the help of his writers is a collaborative amalgam of shrewd social observation, sympathetic insights into human character, breezy pacing and other sophisticated, crowd-pleasing entertainment values. Today we can see more clearly that the vigorous experimentation of his early pictures – his restless searching for an artistic personality that would justify his profession in his own eyes and those of the world – gradually helped him realise where his true strengths as an artist might lie.

Kate Stables reappraises Capra’s ‘It Happened One Night’ in the December 2010 issue of Sight & Sound. The season ‘Rediscovering Frank Capra’ runs at BFI Southbank, London throughout November and December. ‘Forbidden’ is out now in selected cinemas nationwide

Crisis in Happyland: David Mamet on Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, America’s unofficial favourite film (January 2002)

Preston Sturges Box Set reviewed by Brad Stevens (DVD, September 2005)

Bulworth reviewed by Richard Kelly (February 1999)