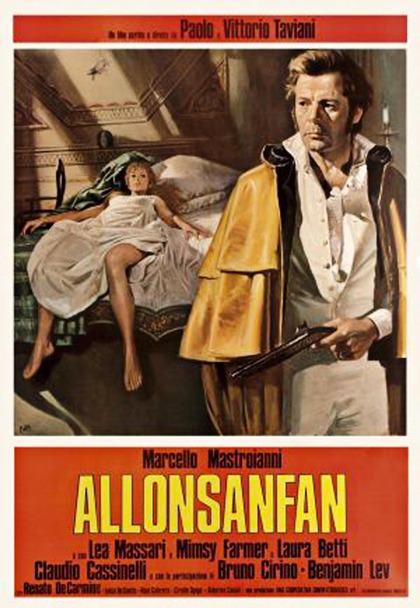

Lost and found: Allonsanfàn

Once arthouse darlings, the Taviani brothers are now shunned by UK distributors. Michael Brooke resurrects their 1974 film Allonsanfàn, a picaresque yarn about ineffectual insurrectionists in post-Napoleonic Italy

Alphabetical proximity aside, there was little that obviously linked Quentin Tarantino with the brothers Paolo and Vittorio Taviani until an unexpected memory jog at the very end of Inglourious Basterds. I’d only seen their 1974 film Allonsanfàn once, probably in the late 1980s, but although my visual memory of it had dimmed to a few images of a scruffily bearded Marcello Mastroianni and a gigantic toad framed by a doorway, I recognised Ennio Morricone’s main theme immediately.

Widely anthologised on Euro-soundtrack compilations as ‘Rabbia e tarantella’, it’s a crescendo perpetuo that constantly feels as if it’s about to erupt into a magnificent main theme, though even the strident brass interruption at the end offers no more than yet another variation on the original riff. It’s a perfect accompaniment for a picaresque yarn about ineffectual insurrectionists in 1816, just after the Napoleonic yoke was lifted from Italy, but decades before the country’s unification.

The Tavianis have been so comprehensively blanked by British distributors since 1994 (when Fiorile opened belatedly to an indifferent reception) that it’s startling to recall how high their profile was after the Palme d’Or-winning Padre Padrone (1977) first put them on the international map. With all their films from those years getting some UK exposure, mostly on the big screen (though 1979’s Il prato/The Meadow went straight to television), they had a better track record than Fellini, never mind their immediate contemporaries. But despite their 15-year run as arthouse darlings, this period only represents the middle act of their career; the five films apiece from the pre-1977 and post-1993 periods have remained almost entirely invisible for UK audiences.

The exception was Allonsanfàn, which was given a belated UK release in 1978, but largely shunned by the repertory-cinema programmers who preferred the brothers’ more immediately accessible later efforts The Night of San Lorenzo (La notte di San Lorenzo, 1982) and Kaos (1984). Aside from a long-deleted American VHS release with reputedly dreadful subtitles, Allonsanfàn doesn’t seem to have been released on any English-friendly video format, and while my imported Surf Video DVD has an excellent transfer, it’s entirely in Italian. The same linguistic restrictions apply to other Italian DVDs of the Tavianis’ early works, but since those films were never released in the UK at all, the opportunity to catch up with them in any form was gratefully seized.

Watching I sovversi (The Subversives, 1967), San Michele aveva un gallo (Saint Michael Had a Rooster, 1971) and Allonsanfàn back to back, it became clear that the Tavianis’ main preoccupation in those early years was the political disillusionment running deeply through Italian society at the time – I sovversi even uses the 1964 funeral of Communist leader Palmiro Togliatti as the starting point for a multi-faceted exploration of where the Left potentially went astray. San Michele, meanwhile, is a direct precursor to Allonsanfàn: set in the 1870s, it follows anarchist internationalist Guido Maneri (Giulio Brogi) as he attempts to turn an Umbrian village into a test bed for his ideas – without much success.

Allonsanfàn’s protagonist Fulvio Imbriani (Marcello Mastrioanni) has the opposite problem. A former aristocrat, he has no shortage of influence or support, thanks to his prominent membership of the underground sect known as the ‘Sublime Brothers’; but his own incarceration has left him thoroughly disillusioned with revolutionary ideals, and determined to start afresh. Self-disgust, however, prevents him from admitting this change of heart even to his former comrades, compelling him to try to undermine their plans without betraying himself – a mission whose ultimately abject failure comes as little surprise.

Allonsanfàn is a much richer film than a simplistic political reading permits. Mastroianni could hardly be more perfectly cast as Fulvio, a man whose every action is marked by a Hamlet-like hesitancy, deriving at least as much from intellectual indecision as from physical cowardice. His tragedy is that, although he repudiates the Sublime Brothers’ methods and ideology, he does so not from a reactionary perspective but from an impossibly idealistic one: like Guido Maneri, he’s a dreamer, not a doer. Accordingly, Allonsanfàn lays Fulvio’s psyche bare in a way that verges on magic realism. The aforementioned toad makes an unexpectedly literal appearance after Fulvio tries to scare his son with a night-time horror story, while a dinner-party game in which representative colours are assigned to his relatives is accompanied by Fulvio repainting them in his mind’s eye.

Visually, the Tavianis’ treatment is as distinctive as a signature: a series of deceptively simple, static compositions in which timeless landscape and architecture implicitly mock the ephemeral human conflict being played out in the foreground. Giuseppe Ruzzolini’s cinematography and Giovanni Sbarra’s production design are immaculate, with Lina Nerli Taviani’s costumes standing out for their conceptual wit as well as their vivid use of colour. The way the Sublime Brothers segue from pointy-hooded KKK lookalikes to nattily red-jacketed insurrectionists creates an effect both absurd and deadly serious – a description that also applies to the film’s very title. The nickname of the son of the Sublime Brothers’ now-dead founder, ‘Allonsanfàn’ is derived from “allons enfants”, the first two words of the ‘Marseillaise’, here infantilised by the removal of the original context. Talking of music, Morricone’s deliciously inventive score is frequently woven into the action, most memorably in the scene in which Fulvio’s sister Esther (Laura Betti) turns a half-remembered ditty into a full-blown song-and-dance number, or when Fulvio himself borrows a violin in a restaurant to impress his son.

Above all, this wittily rumbustious, almost operatic film offers a stirring reminder of a time when European filmmakers regularly engaged with serious political ideas, without compromising their cinematic creativity. Parts of Allonsanfàn, especially the long-shot insurrections themselves, recall the work of Miklós Jancsó, who was ignored in Britain for even longer than the Tavianis, but has recently enjoyed a mini-revival. Is it too much to hope that the Tavianis will get a similar second chance?

What the papers said

“A film of extraordinary density and allusiveness from its opening moments, a torrent of baroque images, extravagant musics and stylistic rhetoric, posited somewhere between 19th-century melodrama and popular opera. Allonsanfàn… aligns itself with other Italian films like Leone’s Once upon a Time in the West and Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Stratagem as a paean to cinema as a revolutionary medium, a medium which can make rhetorical use of material from earlier films, literature or opera, but revitalise it in the transcription. The result may be somewhat muted politically, but it’s aesthetically thrilling.”

— Tony Rayns, Monthly Film Bulletin, August 1978

See also

Lost and found index

Maestros and mobsters: Nick Hasted on a new generation of Italian filmmakers finding its voice (May 2010)

Days of gloury: Quentin Tarantino talks to Ryan Gilbey about Inglourious Basterds (September 2009)

Down with liberty: Michael Wood on Luis Buñuel’s The Phantom of Liberty (September 2000)

Aprile reviewed by Chris Wagstaff (April 1999)