DVD: Jacques Tourneur's westerns

Jacques Tourneur is known for noir and horror. But, argues Tim Lucas, his westerns were every bit as extraordinary

Stars in My Crown

Jacques Tourneur; US 1950; Warner Archive Collection; 89 minutes; Aspect Ratio 1.33:1; Features: original US trailer

Wichita

Jacques Tourneur; US 1955; Warner Archive Collection; 81 minutes; Aspect Ratio 2.35:1

Best remembered for his extraordinary work at RKO Radio Pictures in the 1940s – notably the Val Lewton-produced Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie and The Leopard Man, and the film noir classic Out of the Past – Jacques Tourneur also deserves attention as one of the finest directors of westerns. As with his work in horror and noir, Tourneur’s westerns are uncommonly humanistic, more attuned to internal shadings and conflicts of morality and spirit than to traditional gunplay.

In 1946, he made the splendid Canyon Passage for Universal, starring Dana Andrews and Brian Donlevy as morally opposed friends occupying the romantic indecision of sultry Susan Hayward; the backbone of his 1950s output was a series of Joel McCrea westerns that gave the Sullivan’s Travels lead some of his strongest credentials for starring in Sam Peckinpah’s magisterial Ride the High Country in 1962. Two of these long-unavailable films, Stars in My Crown and Wichita, can now be had as burn-on-demand discs from Warner Archive, while the third (Stranger on Horseback, 1955) remains difficult to see.

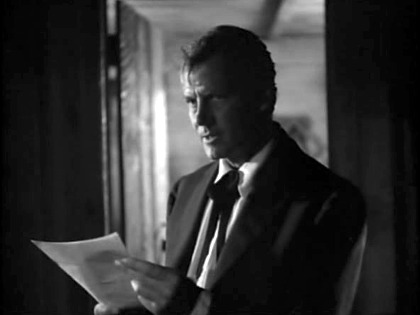

Shot in black and white with all the stellar resources of MGM, Stars in My Crown is more southern than western, but it opens in a western-style saloon as Civil War veteran Josiah Doziah Gray (McCrea, pictured) arrives in 19th-century Walesburg and outdraws the first lost souls he meets for the right to preach them a sermon. The new parson’s story is persuasively narrated by Marshall Thompson, playing the future tense of Josiah’s watchful adopted son John (Dean Stockwell), the orphaned nephew of his wife Harriet (Ellen Drew), as the film settles into an episodic, Ambersonian ramble set during the years when men first put aside their guns to live in civility.

Based on a 1947 novel by Joe David Brown (Kings Go Forth, Paper Moon), the film quickly but deftly sketches a riot of local colour – Jed Isbell (Alan Hale) and “enough tow-headed sons to start a Swedish Sunday school” (the tallest of them a young, unbilled James Arness), the mild and much bullied Chloroform Wiggins (Arthur Hunnicutt), the travelling medicine-show man Professor Jones (Charles Kemper), and craven Lon Backett (Ed Begley), a mine owner covetous of land owned by the ageing black farmer Uncle Famous Prill (Juano Hernandez), whose unambitious refusal to sell prompts a moonlight raid of hooded ‘night riders’ prepared to lynch him.

But the narrative’s real point of conflict is between Josiah and young Doc Harris (James Mitchell), who replaces his dying father (Lewis Stone), courts pretty schoolteacher Faith Samuels (Amanda Blake, Arness’s future Gunsmoke co-star) and stands realistically opposed to the mysteries of faith embodied by the parson – a metaphysical dance of destiny that continues until an outbreak of typhoid brings them together in truce.

Stars in My Crown (ironically named for a cloying hymn disliked by the parson’s wife) was Tourneur’s personal favourite among his films, though he also viewed it as the moment of his professional downfall. His love for Margaret Fitts’s script was such that he offered to direct the picture at no charge when producer William H. Wright couldn’t afford him. Instead, Tourneur accepted a substantial pay cut which reflected badly on him when prospective employers subsequently inquired about his rate.

Though half a dozen Tourneur pictures are more celebrated, Stars is a perfectly made film, raucous with memorable characters and rich dialogue, which makes such an earnest case for the essential goodness of people that its most villainous character is not only redeemed at the end but, in a tiny detail reserved for second viewings, is the first to suggest the cause of the typhoid outbreak. The trailer accompanying the feature is hosted by McCrea and contains unique footage.

Wichita (above), in which McCrea plays Wyatt Earp, is a nicely complementary anti-western – this time in (slightly reddish) Technicolor and CinemaScope – in which the retired buffalo hunter, tired of carrying a gun and looking to start a new business, follows a cattle drive to the Kansas town advertising itself as a place where “everything goes”. When Earp foils an attempted bank robbery, local officials invite him to become their town marshal, but he refuses. Fate intervenes at nightfall when drunken cattlemen (led by Lloyd Bridges and those great western heavies Robert Wilke and Jack Elam) proceed to shoot up the town, killing a young boy in the process.

Much as Parson Gray was able to disperse a mob of Klansmen with no more ammunition than pointed words, the newly badged Earp convinces the rowdies to drop their weapons without firing a shot, leading to an admiring newspaper account account by Bat Masterson (Keith Larsen) and the respect of the town. But Earp’s popularity sours among the officials who hired him – including the father (Walter Coy) of his love interest Laurie (Vera Miles) – when the lawman asserts his authority by forbidding the public to carry firearms.

Wichita is given pleasing complexity by Tourneur’s attention to the unexpected detail. The film’s most powerful sequence comes when Earp, not yet marshal, pays an after-hours visit to the newspaper office of Masterson’s employer, played by 1940s B-movie great Wallace Ford. Here the story stops for nearly six minutes as the men reflect on the events of the day, Ford literally drinking himself past the point of intelligibility. No guns are drawn, but all the film’s drama is concentrated in this sequence as Ford drowns the memory of the night his wife was killed in one of the cattlemen’s shoot-’em-ups, and numbs his dread that the sun is setting in preparation for another.

See also

True Grit reviewed by Ben Walters (February 2011)

Island of lost souls: Graham Fuller on Shutter Island (April 2010)

Man to man: Edward Buscombe on Brokeback Mountain and male bonding in the western (January 2006)

The gun behind the bubbles: John Exshaw on Eli Wallach (January 2006)

The last frontier: David Thomson on Ron Howard’s western The Missing (February 2004)