Film of the month: Incendies

French-Canadian director Denis Villeneuve views the internecine conflicts of the Middle East through the prism of a family tragedy of Greek proportions. By Roger Clarke

Spoiler alert: this review reveals a plot twist

From the outset, Incendies is clearly not going to be your average tale of conflict in the Middle East. We open with a slow, dreamy pan accompanied by a Radiohead song, ‘You and Whose Army?’. We look out of the window on to a scene of pastoral loveliness: palm trees swaying in a warm desert wind, an oasis alive with birdsong and cicadas (Jordan, as immaculately photographed by André Turpin). The camera pulls back as the music wafts, distantly at first – absurd, like a Noel Coward song played at the wrong speed on an old wind-up gramophone. “Come on, come on / Holy Roman Empire / Come on if you think / Come on if you think / You can take us all on,” Thom Yorke croons in words you can hardly make out. A series of almost static framings follows; the children in the shot seem to have a sad, ethereal beauty. It’s puzzling, even as it’s affecting, and for a moment the film seems to teeter on the brink of disaster – it really does look like a plausible Radiohead video for the song being played.

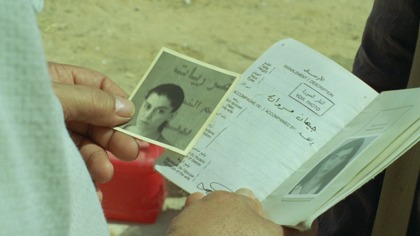

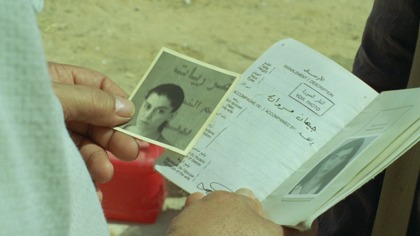

Among the children is one angry boy with three dots on his ankle. The camera zooms in closer and ever closer to his eye, into the well of hatred and abuse that will propel the whole movie. The music continues as we glide forward to a different time frame – contemporary Canada – and alight on a room in a lawyer’s office, impacted with paper files. We move in close on a file marked “Nawal Marwan”. The colour palette changes slightly to a drab, maple beige. It’s as if the director, having delivered a quite shamelessly manipulative emotional punch, suddenly takes everything off the stove and stops cooking.

We now find ourselves in the lives of a brother, Simon (Maxim Gaudette), and sister, Jeanne (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin), attending the reading of the will left by their mother, Nawal Marwan, with whom they had a difficult relationship. The will requires them to travel to her (unspecified) country of origin in the Middle East and hand sealed letters to a half-brother they never knew they had and the father they thought was dead.

French-Canadian director Denis Villeneuve – here adapting (and slimming down considerably) an award-winning three-and-a-half-hour play by Wajdi Mouawad – is a director who knows how to deal with complex issues sensitively. His dramatisation of the 1989 Montreal Massacre – Canada’s Columbine, when 14 female students were singled out for killing by a gunman – Polytechnique (2009) was shot in black and white to minimise its more incarnadine and sensational aspects (the opposite to his thinking in Incendies, with its colour-saturated vision of a bus set on fire after all those inside have been shot). Polytechnique proved Villeneuve had a steady hand when it came to national trauma; he consulted those bereaved by the massacre and specifically excluded the mention of the gunman’s name. This sensitivity is probably the reason why he’s so well regarded in Francophone countries, and why he was seen as the right man for the job by playwright Wajdi Mouawad, who told him to do whatever he wanted with his play – which is just what Villeneuve did.

Just as Villeneuve leaves out the name of the killer in Polytechnique, so in Incendies he leaves out the name of the country. We all know it’s Lebanon, but the liberating aspect of the omission is that it frees him from any need to be literal. As a director he’s never been shy of complex narrative structures, on which he usually hangs consequences of violence – and especially violence against women. Maelström (2000) was a black comedy narrated by a fish, involving a woman coming to terms with an abortion and the accidental killing of a man. Such complexity requires precise editing, and Villeneuve is well served on Incendies by Monique Dartonne, best known for her work with director Tony Gatlif on Gadjo Dilo (1997) and Exiles (2004).

In fact Villeneuve must really have liked Exiles, since he also cast its lead actress in the central role of Nawal: Lubna Azabal, also familiar to Western audiences on the strength of her performance in the Palestinian film Paradise Now (2005), which shares with Incendies a dislike of didactic and ideological positioning. She lends a solemn and shell-shocked intensity to her role as Nawal, whom we see mostly in flashback – first as a rustic in love, until her boyfriend is murdered by her family and her baby taken away to become a boy soldier; then as a middle-class professional turned Baader-Meinhof style assassin; then finally as a prisoner who endures rape as a weapon of war.

Incendies may cover similar literal territory to Samuel Maoz’s 2009 Golden Lion-winner Lebanon, but there’s also a sense of almost trashy, coincidence-based melodrama at work here that’s not usually seen in sombre, sectarian-issue dramas of this kind. The extraordinary thing is that it works. Like Lebanon, it has its roots in that country’s 1980s conflict between Christian and Muslim militias, but where Lebanon toils in the noise and darkness of a tank in battle, Incendies unfolds mainly in the quiet of offices and homes where family relationships break down under intolerable strain.

In some respects, it could be seen as an old-fashioned familial mystery story couched as a war film – for there is war in this film, unfair, stupid and reckless, with whole busloads of people massacred and little children shot down like dogs in ruined streets by stone-cold snipers. This is not war about identity, ideology and explosions; this is war as rape and incest – and parents eating their children, like Saturn in Goya’s famous painting.

Canada’s submission for this year’s Best Foreign Language Film Oscar (it lost out to Denmark’s In a Better World), Incendies is what’s known in Hollywood parlance as a breakout film, with which a director lauded on home territory suddenly becomes known to a far wider international audience. Aside from Lebanon, one comparison would be with Villeneuve’s Canadian compatriot Atom Egoyan. In another universe Egoyan might have pulled off something similar with Ararat, his anguished 2002 misfire about the legacy of the Armenian Massacres. Incendies acquires its heft from some very deep places – Greek tragedy rather than newsflashes. With its shattering encounters between sons and their long-losts parents, it’s almost an anti-Oedipus. (This intertwining of the archaic and the new was something Pasolini understood very well.)

In the end, though, we find ourselves not on the battlefields of Lebanon but on the grey streets of Canada, where the climax comes with the brother and sister’s final delivery of the sealed letters their mother left them, which turn out to go to the same man – a man with a trinity of dots on his ankle. As a moment of revealed horror it is as startling and bare as any in cinema; the summation of all those years of pain and killing is quiet, disgusting – and true.

See also

Blood lines: Denis Villeneuve talks to Tom Dawson about the making of Incendies (June 2011)

Carlos: five hours of the jackal: Olivier Assayas talks to David Thompson about his biopic of the jet-setting terrorist (November 2010)

Lebanon reviewed by Roger Clarke (June 2010)

Invisible lands: Adania Shibli on the films in the Palestine Film Festival (May 2010)

Radical chic: Andrea Dittgen on The Baader Meinhof Complex (December 2008)

Paradise Now reviewed by Ali Jafaar (May 2006)

One Day in September reviewed by Peter Matthews (June 2000)

West Beirut reviewed by Geoffrey Macnab (August 1999)