Spanish spring: cinema after Franco

The death of Franco and the end of dictatorship spawned a remarkable flowering of Spanish cinema at the end of the 1970s. With the revival of Carlos Saura’s Cría cuervos, Paul Julian Smith looks back at key films of the era

What price cinema after the death of a dictatorship? If all goes well we should soon know how the filmmakers of the Arab Spring – in Tunisia and Egypt, at least – cope with both the bracing winds of freedom and the lengthy legacy of repression. Meanwhile the BFI offers Londoners a season devoted to perhaps the most fruitful and hopeful precedent for current events – called, with unambiguous optimism: ‘Good Morning Freedom! Spanish Cinema After Franco’.

The jewel in the crown of the season, rereleased for an extended run, is Carlos Saura’s brilliant Cría cuervos (1975). Yet it’s something of an odd man out. Shot as the dictator lay dying in the autumn of 1975, Saura’s subtle and melancholy drama could not be further from the explosion of vitality and festivity that followed – as documented in many of the other films in the season. The Madrid movida – an untranslatable term originally derived from drug slang for ‘rush’ or ‘buzz’ – was famously an explosion of pent-up cultural energy that expressed itself in multiple media: music, fashion, painting and photography, as well as film. The season includes no fewer than six of the most familiar – and even canonic – texts of the period, namely the early works of Almodóvar.

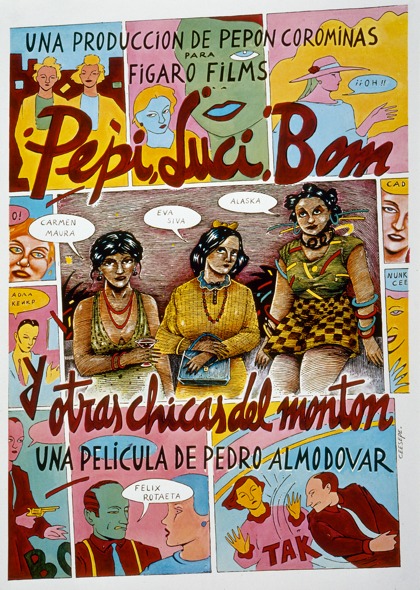

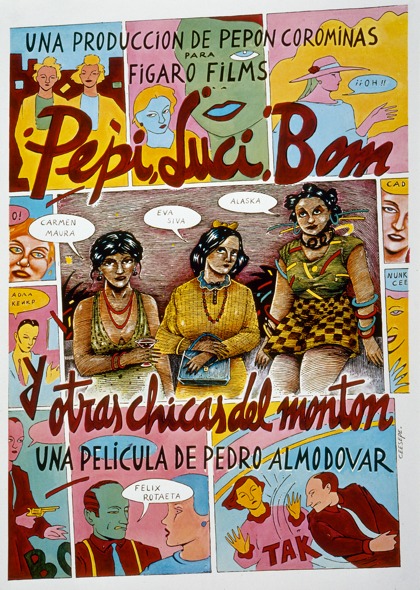

Yet, belying the stereotype of mindless hedonism still current in Spain when it comes to the movida, Almodóvar moves surprisingly swiftly in these films from the crazy and chaotic fun of his first feature Pepi, Luci, Bom (Pepi, Luci, Bom y otras chicas del montón, 1980) to the tragic and accomplished gay love triangle of The Law of Desire (La ley del deseo, 1987). It’s interesting that the BFI’s press release cites mottos of the movida which sound plausible but which I’ve never heard – such as “Madrid nunca duerme” (“Madrid never sleeps”). More famous and typical of the period is the more ominous: “Madrid me mata” (“Madrid kills me”).

As in the case of other narcotic-fuelled subcultures (the Warhol demi-monde or British punk), the movida did indeed prove fatal to a number of its celebrants, casualties of drugs or, slightly later, Aids. The death of a dictator can leave a heavy – as well as a heady – legacy behind it. And the season, which features some gems now little seen even in Spain itself and otherwise unavailable with English subtitles, reveals a variety of coping strategies from very different directors.

To take three exemplary tactics: art-movie auteurs dealt in memory and fantasy; scrappy populists peddled sex and politics; and maudit mavericks immersed themselves in drugs and depression. As we shall see, cineastes explored a common motif that is perhaps surprising in a time that was famous for its festivities (the most notorious party was when Warhol himself briefly lit out from Manhattan for Madrid). That motif is the enclosed house: four walls set against the urgent demands of a changing world outside that had become – all too suddenly – fascinating, challenging, terrifying.

Carlos Saura was of course the ultimate well-established auteur of the period, having enjoyed a lengthy career under the dictatorship stretching back to the neorealist The Hooligans (Los golfos, 1959) via the brutal allegory of fascism as hunting party, The Hunt (La caza, 1966). And Cría cuervos remains an eloquent and moving testament to the end of that era. Starring dark-eyed child actress Ana Torrent, fresh from her triumph in Víctor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive (El espíritu de la colmena, 1973), the film takes place entirely inside the walled compound of a once-powerful family of the regime, hermetically sealed from the chaotic city beyond it, which registers only as jarring traffic noise. It’s an-all female household: traumatised daughters, a mute grandmother, a kindly housekeeper and a chilly aunt.

In the troubling, near-silent prologue, little Ana comes across her father dead in bed after a tryst with an unknown woman. Calmly she takes a glass from his side, washes it in the kitchen and chats with her mother (a heartbreaking performance from Geraldine Chaplin, Saura’s long-time personal and artistic partner). What we only learn later is that Ana believes she has killed the patriarch (is Saura citing Spaniards’ fantasies of murdering Franco, who also died prosaically in his bed?) – and that her mother has also passed away, a victim of cancer. Ana will prove to be plagued by memories of her loving parent; typically, however, Saura chooses not to give us cues when Ana slips into reverie. Even at a moment of huge and undeniable historical change, fantasy and reality slip and slide over each other, fusing and confusing fact and fiction.

This technique is typical of what has been called the ‘Francoist aesthetic’. Faced by harsh and capricious censorship, Spanish filmmakers – chief among them Saura himself – learned from bitter experience to cloak their critique in layers of enigma. So on the one hand, the claustrophobic and decadent house clearly represents the dying days of the regime. The wheelchair-bound grandmother silently contemplates the family photos that chart her only purchase on the past. A large swimming pool, now drained and derelict, testifies to previous moments of pleasure for the privileged winners of the Civil War. The children dress up as adults, mimicking – unknowingly – the deadly conflicts of their elders. The nine-year-old Ana even gets to play with a gun.

Yet there hints, too, of a more open future – a Spanish Spring, if you like. The grandmother listens to old-fashioned songs by Imperio Argentina, a vital figure for the regime, who even made films in Nazi Germany. But the girls dance instead to ‘Porque te vas’, an incongruous and mindlessly sunny pop ditty by Jeanette, a briefly famous star of the 1970s. Daringly, Saura casts Chaplin in a double role: as the dying mother and as the grown-up Ana, who addresses the camera directly from a point in the distant future where she herself has become an adult.

The moral is, as ever, ambiguous. If mother and daughter are indistinguishable (and Chaplin is as handsomely tormented in both roles, emotion flickering over that luminous face), how can Spain move on? Will it be locked into a cycle of repetition and repression? The proverb cited in the film’s title (“Raise ravens and they’ll peck out your eyes”) would seem to be pretty clear. Yet by simply positing the possibility of a future – at a time when many Spaniards feared another Civil War – Saura might be seen as assuring us that life would indeed go on after the death of the dictator, however inconceivable that prospect might have seemed at the time.

Lost in transition

Saura’s own future would prove to be problematic. He hit his stride in the 1980s with a trilogy of dance movies (Blood Wedding, Carmen, A Love Bewitched), but subsequently failed to impress either audience or critics with historical epics (El Dorado, 1988) or thrillers (Taxi, 1996). Compared with other, younger directors in the season – true inheritors of the Spanish Spring – Saura seems to come not just from another decade, but from another century.

Little known abroad, and almost forgotten in Spain, is Eloy de la Iglesia, an exploitation filmmaker who made pioneering works on two formerly forbidden themes: Basque nationalism and homosexuality. As furiously (and briefly) prolific as Fassbinder, de la Iglesia made no fewer than 20 films during the period known as the ‘Transition’ to democracy. Despised by critics, he won huge audiences for features he himself described as “pamphlets”: scandalous, date-tied chronicles of politics and sex.

Made in 1978 – just three years after Cría cuervos – Confessions of a Congressman (El diputado) is a typically trashy masterpiece. Hero Roberto (played by José Sacristán, the ubiquitous film face of the new Spain) has lived life as a leftist in secret under Franco. Now, with the arrival of democracy, he confronts another kind of existence on the down-low: though happily married and a political candidate, he is drawn to the tempting rent boys who seem to be everywhere in de la Iglesia’s vision of a sex-soaked Madrid.

Cheerfully slapdash in technique, and hijacking real-life public figures of the time for cameos, Confessions of a Congressman still brings with it a heady whiff of hedonistic times. And its central moral remains relevant today: even in a Spain where gay marriage is now unexceptional, there are vanishingly few out politicians. Cruising in his car (a delirious montage shows a string of interchangeable Pasolini-esque youths), Roberto soon comes to focus on one particular blond angel. But what’s striking about the film (which ends as Roberto intends to come out to his homophobic party colleagues) is that the open but perilous pleasures of the street give way to the more sheltered delights of the home. Roberto’s accommodating wife, a truly modern woman of the period, is happy to welcome the boy into her marriage; and the most scandalous scene (echoed by a triple kiss on the original poster) is a sexy three-way between the middle-aged politician, his well-groomed spouse and the barely legal blond boy.

Here Saura’s decaying fascist mansion has been replaced by the fashionable bourgeois home in which progressive leftists can enjoy – unseen – their newly transgressive pleasures. And the subtle exploration of memory and fantasy could play no role in an era named for the destape – a Spanish word meaning literally ‘uncovering’ or ‘revealing’, but used for the disrobing of the young bodies now ubiquitous in the new Spanish cinema. It was a trend for which the populist de la Iglesia, a lone pioneer of male frontal nudity, was notorious.

Transgressive aesthetics

Unlike Carlos Saura, whose career has spanned 50 years (and who is still going strong at 79), the briefly prolific de la Iglesia soon sank into silence, dogged by the drugs that feature so heavily in his films. Yet another director featured in the season, Iván Zulueta, met a similar fate after his extraordinary and little-seen feature Rapture (Arrebato, 1980). It would be quite possible to imagine an alternative universe in which it was not Almodóvar but the maverick Zulueta who had become the dominant auteur of post-Franco cinema. After all, Almodóvar’s Pepi, Luci, Bom is – however cheerfully vibrant – a hot mess of a film; released the same year, Rapture is by contrast surprisingly accomplished in both its narrative and technique.

The two novice auteurs seem to have had much in common: a taste for transgressive aesthetics and thematics; a love of genre film and pop culture; and a lack of concern for politics – at least in its parliamentary form, still new in Spain. They also shared an interest in transmedia: Almodóvar had experience in print and fotonovela, Zulueta a background in television and graphic art – especially the movie posters that would prove to be his most enduring medium. The two directors even shared actors: of the two stars of Rapture, Eusebio Poncela would go on to play a very similar part, also as a filmmaker, in The Law of Desire, while Cecilia Roth, after a cameo in Pepi, Luci, Bom, would star again for Almodóvar in Labyrinth of Passion (Laberinto de pasiones, 1982). One lip-synching scene in Rapture when Roth channels Betty Boop – a scene that’s at once charming and alarming, a combination typical of Zulueta’s film – prefigures so much in Almodóvar’s films to come.

Known as the definitive cult film of the movida, Rapture charts the weird cinematic romance – a threesome once again – between a genre director (Poncela’s José, shown cutting a vampire flick in the opening sequence), his junky lover (Roth’s Ana, turned on to heroin by her boyfriend) and a reclusive super-8 filmmaker named Pedro (played by the little known and surely pseudonymous Will More), who invites the couple to his bizarre country estate. José is first seen driving along an infernal Gran Vía (Madrid’s Broadway), glowing with the movie posters of picture palaces (now sadly closed) to the accompaniment of Wagner – Zulueta’s precursor in terms of rhapsodic excess.

In José’s chaotic apartment, whose lighting glows ruby red, Ana is sprawled on the bed, all luscious scarlet lips and furry high-heeled mules. The sound design features sirens and alarms, proper to a city of extremes. We are then treated to fetishistic close-ups of shooting up heroin, with addicts’ skin tinged an unearthly lavender. This casual drug use is matched by equally casual nudity (both male and female) typical of the destape. But what’s specific to Zulueta is this theme of the rapture of addiction, to which his title alludes. It is a double addiction, to both heroin and to celluloid.

The film is structured around the hazy chronology of addiction (characters ask each other “when was it?” that an event took place) and an equally blurry, druggy geography (a trip from nearby Segovia to Madrid is compared to a space flight from Venus to Pluto). And in the final section, when Pedro has relocated to a sterile modern apartment building in the capital to practise his cinematic obsession, film will be reduced to the minimalism of the avant garde: rhyming with Poncela’s blood-red shirt, Pedro’s footage has become a strip of all-red celluloid, except for a single frame that starts into life.

It’s a long way in a short time – just five years – from Saura’s shuttered house, echoing with fantasy and memory, to Zulueta’s equally hermetic apartment, immersed in drugs and depression. And on that brief, intense journey, de la Iglesia, among others, had shown with new and fragile urgency the unaccustomed power of sex and politics – of sex in politics – in a young democracy.

Perhaps ‘Good Morning Freedom!’ is too optimistic a slogan for the films of the period; in Spain the legacy of repression proved difficult to slough off, as perhaps it will prove in the Arab world. But, as Saura knew full well when in Cría cuervos he had Geraldine Chaplin address us so solemnly from the uncertain world of the future, the bracing winds of freedom include the freedom to choose self-destruction. This was the road taken by de la Iglesia and Zulueta – a road so different to the better-known and richly creative self-promotion of Almodóvar. As this season reveals, Spanish cinema after Franco would thus prove – perhaps inevitably so – richer, stranger and more incorrigibly ambivalent than the dictator’s orphaned subjects could possibly have imagined.

‘Cría cuervos’ is rereleased on 10 June at BFI Southbank, London and cinemas nationwide. The season ‘Good Morning Freedom! – Spanish Cinema After Franco’ runs until 30 June at BFI Southbank

See also

Hidden visionaries: Mar Diestro-Dópido on a touring exposition of 50 years of Spanish experimental cinema (April 2011)

Iván: Pedro Almodóvar’s eulogy to his late friend Iván Zulueta (English translation, April 2011)

Critics’ inspirations: Mar Diestro-Dópido on La Movida, Spain’s post-Franco cultural explosion (April 2011)

Iván Zulueta, 1943-2009: obituary by Belén Vidal (March 2010)

Only connect: Paul Julian Smith on Almodóvar’s

Talk to Her (July 2002)

Goya in Bordeux reviewed by Paul Julian Smith (November 2000)

Flamenco reviewed by José Arroyo (August 2000)

Silicone and sentiment: Paul Julian Smith hails Almodóvar’s All About My Mother (September 1999)

Tango reviewed by Geoffrey Macnab (August 1999)