Comment

Women on film: the ladies vanished

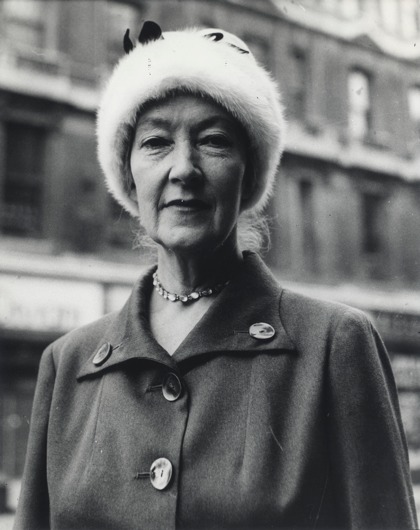

The late film critic Dilys Powell

Hannah McGill wonders where all the women critics went – and why

» See our Women on film competition for female film writers

Recently the eminent film academic Annette Kuhn wrote to Sight & Sound to express alarm at the small number of female critics whose views had been included in the magazine’s June poll on important film books.

It’s not the first time that this and other film journals have been taken to task for underrepresenting women in such surveys of informed opinion. In 2008, Jennifer Merin criticised both Cineaste and Sight & Sound for including scant females in their respective symposia on the future of criticism. (Sight & Sound’s rating unfortunately dropped even lower – to nought – when it was pointed out to Merin that Kim Newman is a man.) S&S’s Nick James noted at the time that women approached to participate in this particular brand of professional navel-gazing often failed to respond: “It’s certainly the case that men are generally much more enthusiastic about this kind of exercise, which may make us the sadder sex.”

In which there is undoubtedly considerable truth; recreational list-making might broadly be said to turn men on more than women, as might the formation of pithy statements about Where Things Are Going. I’ve definitely ducked out of or missed the deadlines for a few Critics’ Polls, because I find them horribly difficult to do; I don’t tend to deal in absolutes regarding ‘the best’ this or ‘the most important’ that. That’s not necessarily a gender thing – because almost nothing is necessarily a gender thing – but whether it’s due to nature or nurture, certain conclusions can be drawn from things men and women prioritise and do for fun. Completism in the amassment or experience of cultural objects, and the ordering of those objects according to perceived significance, quality or placement in the alphabet, are tendencies associated more with the boys.

Even if you accept such a difference in gender behaviour as a given, however, it doesn’t entirely explain the scarcity of women in critics’ polls. There aren’t very many women film critics consulted polls because there aren’t very many women film critics. A piece of 2007 research by Martha Lauzen found that 70 per cent of the movie reviews published in America’s top 100 daily newspapers were written by men, and that 47 per cent of those publications ran no film reviews written by female critics.

In the UK, you just have to flick through the papers and magazines to notice that few women’s names crop up in review bylines. As in the States, of those that there are, many are excellent, and many are influential. But the numbers speak for themselves: it’s hardly a level playing field.

One might understand this were film more obviously a ‘boys’ club’ in every regard; but the discrepancy in critic numbers doesn’t seem to be reflected in dwindling female audiences, or in insignificant numbers of female film students and film academics. When I was artistic director of the Edinburgh International Film Festival, our market research showed up an audience that was slightly more female than male. So much for festivals – with their predominance of foreign-language, arthouse and genre content – being geeky male enclaves.

That said, it’s hardly a shock to learn that women make up a negligible percentage of the world’s paid and prominent film critics. Women tend to make up a negligible percentage of a great many professions that involve bullish ambition, carry authority and social standing, and are largely policed by male gatekeepers. Blame men, blame women, blame nature, but it’s so.

What’s interesting in the case of the paucity of lady film critics is that it was not ever thus. No list (made by man or woman!) of the most influential and celebrated film critics of all time would be complete without the names of Iris Barry, Dilys Powell and Pauline Kael. Those are only the famous and enduring examples; like screenwriting, cinema criticism had a lot more women in its ranks when it was regarded as low-status hackwork. Kay Bourne, who served as arts editor of Boston’s Bay State Banner for 40 years, has pointed out that all of the working film critics in Boston were women “until, in the 1960s, film exploded as an important art. Then men came in wanting the reviewing jobs.” When ‘women’s pictures’ receded in prominence, male auteurs swaggered to the fore and film fandom and film expertise became macho adornments, lady critics declined in prominence.

Ironically, though being critical is frequently counted as a female trait (hence the adjective ‘bitchy’), and although Barry, Powell and Kael went a long way towards defining what a film critic is and does, film criticism in this day and age still seems to sit more comfortably with men. Alizah Salario has argued that this reflects a general cultural resistance to opinionated women. “Critics can’t be afraid of hurting someone’s feelings… They must be assertive, authoritative, outspoken and downright ballsy – all traits traditionally associated with men… I’ve wondered if there are fewer female critics in prominent publications not because we aren’t out there, but in part because the combination of ambition, intelligence, and audacity does not always work in a woman’s favour.” Girls might forge ahead academically at UK schools, but do they still grow up afraid to step out of line, afraid to cause offence? The critic who makes his or her opinion public and stands by it has to be pretty bulletproof – especially in these days of vitriolic online commenters and feud-making bloggers.

Of course, quibbling about the makeup of the critical community might be a luxury we can ill afford, when critics of all shapes and sizes are finding it hard to stay in work. Stephanie Zacharek of Salon.com identifies a timing issue: “Right around the time major newspapers… began expressing a willingness to hire women critics, they also began to realize that maybe they didn’t have enough money – or enough faith in the idea of criticism, period – to support having full-time critics of either gender.” Crises do provide an opportunity for reassessment, however. Little doubt that criticism, wherever it’s headed, needs new voices and attitudes to help it survive. Perhaps a broader demographic of critics would help to furnish those.

Correction (20 May 2011): This article originally asserted that the Edinburgh Film Festival’s audience was “slightly more male than female”; the reverse wording was intended and has now been inserted.

See also

Critics on critics: leading critics choose the works of criticism which have had the greatest impact on them (October 2008)

What goes around: Margarethe von Trotta’s history plays: Sophie Mayer on the indefatigable feminist of the once-New German Cinema (March 2011)

The Blonde: icon, stereotype, concept: what is it that fascinates filmmakers about the blonde, asks Lucy Bolton (February 2010)

Day of the woman: B. Ruby Rich on Kill Bill Vol. 2 (June 2004)

Day in the life: Sheila Johnston on The Hours (February 2003)

Sick sisters: Linda Ruth Williams on Baise-moi (July 2001)

Take it like a girl: B. Ruby Rich on Girlfight (February 2001)

Women directors special: soul survivor: Kate Pullinger on Jane Campion’s Holy Smoke (October 1999)