Primary navigation

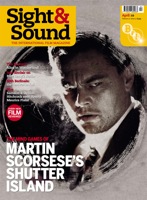

Scorsese's Shutter Island may be a faithful adaptation of a bestseller, but it’s also his deeply felt homage to the cinema of the 1940s and 50s, says Graham Fuller, and a return to the paranoid interior world of Taxi Driver

SPOILER ALERT: This piece gives away a major plot twist

Pull yourself together,” US Marshal Teddy Daniels (Leonardo DiCaprio) urges himself at the beginning of Martin Scorsese’s madhouse thriller Shutter Island. Crossing Boston Harbour by ferry on a stormy day in 1954, Teddy has just vomited into a toilet bowl and must get to his feet, wash his face and join his new partner Chuck Aule (Mark Ruffalo) on deck for the approach to the eponymous rock. They’re there to visit the Ashecliffe hospital for the criminally insane, ostensibly to find a filicidal maniac who’s escaped from her locked cell. That “pull yourself together” isn’t about quelling seasickness, however – it’s Teddy’s unconscious warning to himself that he must gather up the shards of his shattered psyche, or endure the unthinkable. The significance of the words may only resonate retrospectively, but the coincidence of Teddy’s nausea with the doom-laden fog-horn quavers of Krzysztof Penderecki’s ‘Symphony no. 3: Passacaglia – Allegro moderato’, which sounds as the marshals sight the island, suggests that the horrors to be revealed there will have a personal provenance. This is immediately underscored when Teddy alone makes eye contact with a ghoulish female inmate in the hospital garden, who gestures to him to keep shtum.

Teddy’s psychological disarray is mirrored by the narrative, a mosaic of his past and present realities, his memories, dreams and hallucinations. During meetings with Ashecliffe’s head psychiatrist Dr Cawley (Ben Kingsley) and his sinister German colleague Dr Naehring (Max von Sydow), Teddy experiences flashbacks to 29 April 1945, when he was one of the American soldiers who liberated Dachau concentration camp. He sees again an exterminated mother and daughter embracing in a pile of frozen bodies and, amid a tornado of Nazi papers, the quivering death throes of the commandant, who has botched his suicide – and whose suffering Teddy prolongs. He recalls too the Americans’ massacre of SS guards, which Scorsese recreates with a terrifying tracking shot along a line of falling men. Teddy believes he initiated the slaughter, though Cawley casts doubt on whether he participated in it at all – an important detail, since it shows that Teddy’s memories may not be reliable.

Teddy admits to Chuck that he sought the Asheville assignment because he is on a private revenge mission against one Andrew Laeddis, whom he believes to be a patient there; two years before, Teddy says, Laeddis started the fire that killed his beloved wife Dolores (Michelle Williams). The Dachau trauma coalesces in his dreams (overdetermined as they are) with visions of Dolores dressed in a jarringly bright yellow floral-print dress, her hair unaccountably wet, warning him about Laeddis and the escaped woman, Rachel Solando. As they talk, a blizzard of black ash swirls around them – the appalling origin of which may only dawn on the viewer gradually – before Dolores’ charred body crumbles in Teddy’s arms.

Some critics have taken issue with Scorsese’s use of Holocaust imagery, but he is too serious an artist to aestheticise the Nazi horror unthinkingly. Shutter Island may be an entertainment culled from low-art pulp fiction, film noir and B movies, raised to a higher level by Scorsese’s kineticised classical stylisation, but it is also a genuine study of madness in which the protagonist conflates the evil he has been exposed to with his own crimes and associative guilt. The swirling ash and the spectre of Emily Mortimer (who plays one incarnation of Rachel as well as Dolores’ doppelgänger) and a little girl waking in the Dachau ice are part of a phantasmagorical procession of images in a diseased mind. For Teddy, we will learn, is mentally ill, as was Dolores.

Scorsese’s poetic approach to the material and his harnessing of the horror and noir genres to tell the story trivialise the Holocaust no more than did, say, Alan J. Pakula’s conventional dramatic approach to his 1982 film of William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice. The comparison between the two pictures is worth making, since Teddy and Sophie are both, in their different ways, damaged products of the death camps who are fatally involved with schizophrenics (here, Dolores; in Sophie’s Choice, Nathan, the character played by Kevin Kline). Part of Teddy’s maladjustment on returning from the war is that he is married to Dolores, and unable or unwilling to see that she is unbalanced.

If Shutter Island makes an error in taste, it’s not in its images of Dachau, real or oneiric, but in Dolores’ nasty smirk and her reply, spoken with a clichéd horror-movie lilt, when Teddy questions her about their three missing children in the revelatory sequence at the end of the film showing what became of her and why her hair was wet in the dream.

A hidden world

Although Shutter Island is expanded topographically by aerial shots – Teddy and Chuck contemplating the rugged cliffs surrounding the hurricane-ravaged island, Teddy’s journey to the lighthouse for an (anti-) climactic showdown with Dr Cawley – it’s an intensely claustrophobic piece, in contrast to Scorsese’s last three features (all with DiCaprio): Gangs of New York (2002), The Aviator (2004) and the Oscar-winning The Departed (2006). Lurid and labyrinthine, it returns him to the paranoia-ridden B-movie terrain of Taxi Driver (1976) and After Hours (1985) – and to a lesser extent Bringing out the Dead (1999) – with all of which it shares a nightmare-like progression and atmosphere. Instead of the streets of New York, Teddy must negotiate an isolated asylum where identities shift, and the greatest threat comes from what cannot be seen.

Shutter Island is faithfully adapted by screenwriter Laeta Kalogridis from Dennis Lehane’s 2003 novel, which itself was influenced by B movies. The project came to Scorsese at an auspicious moment, when he was producing and narrating a 2007 documentary about the producer-writer Val Lewton, whose RKO horror cycle foregrounded psychological over physical terrors. The Lewton films included Mark Robson’s The Seventh Victim (1943), Isle of the Dead (1945) and Bedlam (1946), each of which feeds directly into Shutter Island. The Seventh Victim was among the films Scorsese showed members of the cast and crew during production; Isle of the Dead, Scorsese once recalled, scared him to death as a child.

A greater talent than Robson was Jacques Tourneur, whose three films for Lewton – Cat People (1942), I Walked with a Zombie (1943) and The Leopard Man (1943) – demonstrated the suggestibility of imminent atrocity by shrouding the threatening agent in shadow. Also among the Tourneur movies Scorsese showed his team was Out of the Past (1947), and he surely had that serpentine noir in mind, no less than Tourneur’s horror films, when he wonderfully evoked the director’s oeuvre in his 1995 documentary A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies: “Tourneur’s twilight zone was a labyrinth. His were perilous journeys into the unknown… Reality remained opaque, and rarely were people what they appeared to be; they stood at the frontier of a hidden world – a shimmering canvas of distant murmurs and deep shadows. There was a muted disenchantment in Tourneur’s films, a strange melancholy, the eerie feeling of having embarked on an adventure from which there was no return.”

Out of the Past

As much as this description captures the existential plight of Jeff Bailey (Robert Mitchum) in Out of the Past, it also conjures Teddy’s hopeless and hapless journey through the gothic fastness of Ashecliffe where, unbeknown to him, he is an exceptionally violent patient fighting for his sanity in a “radical, cutting-edge role play” experiment, which Dr Cawley hopes will avert the need to give him a transorbital lobotomy. Neither of the two Rachels in the film – Mortimer as the missing murderess, who shows up as mysteriously as she disappeared, and Patricia Clarkson as a renegade doctor hiding out in a firelit cave from Cawley and the hospital wardens – are who they say they are; nor is Chuck, the laidback sidekick marshal from Seattle. (An early clue is that he fumbles his gun when taking it from its holster to give to the wardens on arriving at Shutter Island, which makes Teddy wonder why he isn’t doing it with professional ease.)

Imaginary prisons

Tourneur’s “shimmering canvas of distant murmurs and deep shadows” is most potently rendered in Shutter Island in Ashecliffe’s C block, which Teddy and Chuck bluff their way into in search of Laeddis, having swapped their civvy suits, colourful ties and fedoras for white orderly uniforms. This fearsome redoubt dates from the Civil War, but its aspect is medieval – it’s a castle of horrors from Poe or, for that matter, Roger Corman; instead of “distant murmurs”, they hear the distant howls of the mad. Separated from Chuck, Teddy creeps through its dripping passageways and chambers, at one point confronted by a vertical maze of cages and galleries reminiscent of Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s etchings ‘Carceri d’invenzione’ (1749-61), or ‘imaginary prisons’, senseless structures that occupy space irrationally. The implication is that Teddy (who, after a 24-month course of the antipsychotic drug Chlorpromazine, has smoked medicated cigarettes and been given more pills to overcome his crashing migraines since arriving at Ashecliffe) has been induced into the darkest recesses of his mind in order to find a logical way out.

Looming out of the shadows to plague Teddy during the C block episode are leering horror-movie bogeymen, one of whom, George Noyce (Jackie Earle Haley), raves about atolls and hydrogen bombs, a reference to America’s first detonation of an H-bomb at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific on 1 March 1954. He is another projection by Teddy, who – to cite Lehane – has foisted his fears of “Third Reich-inspired surgical experiments, Soviet-inspired brainwashing” on the doctors at Ashecliffe, programmes supposedly funded by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Dipping his toe into the same waters as Samuel Fuller’s Pickup on South Street (1953) and Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955), Scorsese thus also avails himself of Cold War paranoia – though it’s the opening sequence on the ferry, when DiCaprio and Ruffalo are at their most persuasive as noir law enforcers of the era, that most viscerally instils dread. Complaints that too many hot-button issues are crammed into this the story miss the point: the piling on of Teddy’s anxieties builds not only a portrait of a paranoiac but of the jittery 1950s, which Scorsese said in A Personal Journey were “a fascinating era when the subtext became as important – or sometimes more important – than the apparent subject matter.”

Spellbound

“This is a game,” Noyce tells Teddy. “All of this is for you… If you don’t let it go, you’ll never leave this island” – “it” being Teddy’s mistaken belief that Dolores died in a fire. This tip-off to Teddy that he is being manipulated for his own benefit comes well before the end of the movie, alerting the audience to the idea that he, too, is not what he seems – and to the delusory nature of Shutter Island as a spectacle. The gradual breaking down of Teddy’s perceived reality, mirroring the viewer’s experience, is akin to that of Peter Carter (David Niven) in Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death (1946), who experiences a series of “highly organised hallucinations comparable to an experience of real life, a combination of vision, hearing and ideas,” and requires brain surgery to save him and restore his consciousness to normal.

Scorsese’s serious creepshow shocker, then, is both his most self-conscious movie in terms of its deceptive text, and his most rigorously psychoanalytic, analogous to Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945) in its depiction of psychiatrists creating the circumstances for a patient’s recovery. “Psychoanalysis reassorts the maze of stray impulses, and tries to wind them around the spool to which they belong,” Freud told George Sylvester Viereck in 1930. “Or, to change the metaphor, it supplies the thread that leads a man out of the labyrinth of his own unconscious.” In the lighthouse with Cawley, Teddy grasps the mythical thread, only to let it go the next day in a conversation with Chuck, who is actually Teddy’s primary psychiatrist (and therefore unused to handling guns). It’s not clear if Teddy does this deliberately, choosing lobotomy as his penance for the death of his wife and children. If so, it’s a final thrill we can do without.

‘Shutter Island’ is reviewed the April issue of Sight & Sound

Scorsese online rarities: early shorts and documentaries, sponsored films and cameos collected by Guillaume Gendron (online, March 2010)

Messiah of Evil reviewed by Tim Lucas (January 2010)

Moving at the speed of emotion: Scorsese discusses Thorold Dickinson’s career with Philip Horne (November 2003)

Bringing Out the Dead reviewed by Kevin Jackson (January 2000)

Death’s cabbie: David Thompson on Scorsese and Paul Schrader’s reunion on Bringing Out the Dead (December 1999)