DVD: The Conversation

USA 1974

Reviewed by Michael Brooke

Review

The Conversation

Francis Ford Coppola; US 1974; StudioCanal / Region 2 DVD / Region B Blu-ray; Certificate 12; 108/114 minutes; Aspect Ratio 1.85:1 (DVD anamorphic); Features: commentaries by Coppola and Walter Murch, interviews with Coppola, Gene Hackman and David Shire, screen tests, script extracts, booklet

When The Conversation premiered in April 1974, Francis Ford Coppola’s psychological thriller about a surveillance expert was assumed to have been directly inspired by the then unfolding Watergate scandal, though the original script had been written in the late 1960s. Still, this could only enhance its appeal to the cognoscenti (the following month, it would win the Palme d’Or; the following year, an Oscar nomination for best picture), and by a fortuitous coincidence this Blu-ray and DVD reissue comes at a time when the film’s central theme has rarely been so prominent or widely discussed.

To underline this, the review copy arrived on the day when a woman’s xenophobic outburst on a South London tram had been covertly filmed and uploaded to YouTube for the voyeuristic delectation of hundreds of thousands, and when the ongoing Leveson Inquiry into UK press standards was probing a seemingly systemic use of eavesdropping that Coppola’s protagonist Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) would completely recognise. Indeed, Glenn Mulcaire, the much vilified News of the World voicemail hacker, is close to a real-life equivalent, his obsessively meticulous record-keeping ultimately providing rather more evidence of wrongdoing than his paymasters would ideally have liked. When The Conversation was made, remotely operated public CCTV cameras of the kind that Caul briefly plays with during an equipment fair had only recently been installed (in New York’s Times Square, in 1973); now, they’re ubiquitous.

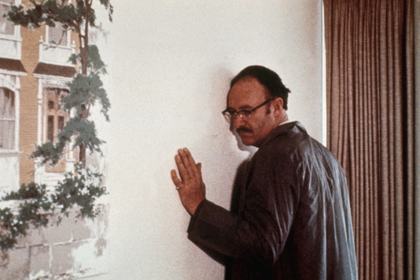

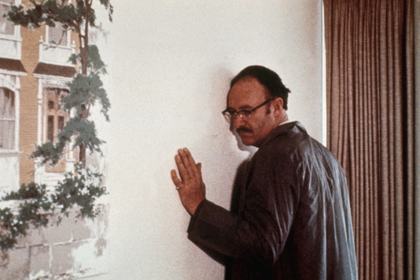

Caul would doubtless regard all these developments as an irritating and deeply unwanted encroachment on his own professional fiefdom. Hackman’s intensely withdrawn performance, the hardest kind for a leading actor to bring off (especially an extrovert like Hackman), only comes to animated and enthusiastic life when Caul is discussing technology and technique: at all other times his life is strictly controlled and compartmentalised, with even sex arranged by appointment.

A hard-earned understanding of the nature of sound, from its original production through to recording, enhancing and editing, means that Caul can pull off the seemingly impossible feat of recording an entire conversation between two people (Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest) walking around a crowded and noisy public space, while taking into account the fact that they’re expecting to be spied on and constantly vigilant. When he plays back the tape in its final edited form and explains how he did it in exhaustive and borderline nerdish detail, he’s proudly unveiling his masterpiece.

Where things go badly wrong is when Caul then switches from professional snooper to amateur sleuth. Just as a misinterpreted voicemail message or paparazzi snapshot can land a newspaper with a hefty libel settlement, so Caul’s attempt at interpreting the meaning of the conversation, second-guessing its possible consequences and attempting to prevent what he believes to be an imminent tragedy, is both misguided and, ultimately, professionally and psychologically devastating. It’s easy to understand his curiosity from a human perspective, since the behaviour of his employers (fronted by a repellently unctuous pre-stardom Harrison Ford) is so patently suspicious and the prospect of a murder seemingly all too real – but it’s also none of his business, hard though it must be for “the best bugger on the West Coast” to accept that argument.

Caul’s onscreen perfectionism is matched by the behind-the-scenes alliance between Coppola and his co-auteur Walter Murch, who oversaw the film’s editing and post-production while Coppola was busy making The Godfather Part II. The opening scene in San Francisco’s Union Square, in which the conversation is recorded in the first place, remains a masterclass of staging and editing, the soundtrack constantly dissolving into electronic chirrups (just as the 35mm version drove unprepared projectionists spare, so this version will cause equipment-conscious domestic viewers to momentarily panic about their speakers) as Caul and his team, which includes John Cazale in the second of his five films, constantly track and retrack their quarry, attempting to frame and focus the sound with the same precision as Haskell Wexler’s camera (Wexler shot this sequence before being replaced by Bill Butler).

As with earlier DVD and Blu-ray releases of Coppola’s back catalogue, The Conversation was repackaged by his own American Zoetrope company, with Coppola himself credited as the project producer. The Blu-ray transfer isn’t quite perfect, as there’s a faint but perceptible sheen of digital noise, but it’s mostly very satisfying indeed. The surround soundtrack has considerably more authority than many such remixes, having been supervised by Murch himself, but purists will be grateful for the inclusion of the mono original. Extensive extras start with two nicely divergent commentaries from Coppola and Murch: unsurprisingly, the former is more generalised, the latter more technical.

Other extras include interviews with Hackman (1974) and composer David Shire (2011), archival screen tests (including Harrison Ford trying out the Frederic Forrest role), on-set footage of Coppola directing Hackman and lengthy excerpts from the screenplay presented both in onscreen facsimile and via Coppola’s own dictated recordings. But perhaps the most appropriate extra is a short video piece that compares shots from the film with their real-life locations nearly 40 years on, a neatly microcosmic illustration of the way The Conversation plays out in 2011, with some things changing totally while others remain unsettlingly similar.

See also

How to tell a true war story: Nick Pinkerton on Apocalypse Now, Taxi Driver, Cutter’s War and how Hollywood’s auteur generation distilled the Vietnam War into a new form of vigilantism (May 2011)

Down in the hole: Kent Jones on The Wire (May 2008)

Royal rapscallion: Andrew Collins on Gene Hackman (November 2005)

Casualties of war: Philip Horne on Apocalypse Now Redux (November 2001)

My bloody valentine: Anthony Minghella and Walter Murch talk to Nick James about The Talented Mr. Ripley (February 2000)

Now you has jazz: Laura Mulvey on ‘canned vaudeville’ and the advent of the talkies (May 1999)

The Outsiders reviewed by Gilbert Adair (Autumn 1983)