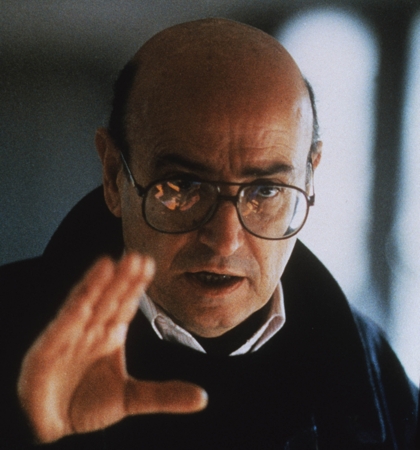

Theo Angelopoulos: the sweep of history

Editor’s note (25 January 2012):

In memoriam

We were shocked and saddened to hear of the death last night of Theo Angelopoulos, one of the true greats of world cinema. The 76-year-old director was hit and killed by a motorcycle while crossing a road near the set of The Other Sea, which as discussed below was to be the closing chapter of a trilogy after 2004’s The Weeping Meadow and 2009’s The Dust of Time, his most recent features.

David Jenkins interviewed Angelopoulos last November for this article, which runs in our current February issue; we published it online two weeks ago. Time seems to have suddenly moved very fast, but we hope that David’s appraisal of Angelopoulos’s career, and the director’s own recent voice presented herein, will serve to honour the achievements of this master of the historical fresco and trailblazer of the sequence shot.

An obituary will run in our March issue. In the meantime, this transcript of a substantial interview conducted by Geoff Andrew with Angelopoulos on stage at the National Film Theatre in 2003 is further recommended reading.

— Nick Bradshaw

Photo courtesy Kobal Collection

The features of Theo Angelopoulos have defined a contemplative style of European filmmaking that’s as instantly recognisable as it has been influential. As the Greek director’s complete back catalogue is issued on DVD, he talks to David Jenkins

I remember overhearing a joke at a film festival a few years ago. One man said to the other, “You know when you’re watching a film by Theo Angelopoulos. As it starts, you check your watch and it says six o’clock. Three hours later, you check your watch again and it says five past six.” Irreverent though it was, in retrospect there was a strange pertinency to his quip: Angelopoulos does indeed forge films where time – and indeed history – feel as if they have come to a glorious standstill.

His stock-in-trade is the immaculately choreographed sequence shot in which his camera lopes ominously and gracefully across landscapes, through rooms, shacks, courtyards, over and around huddled crowds of people who themselves produce artful formations as they mingle within the frame. His colossal geopolitical masterwork from 1975, The Travelling Players (O thiassos), offers just 80 separate shots during its four-hour running time. History, catastrophes, celebrations, political intrigues, social shifts are rarely recounted in the traditional linear sense – rather, they are daubed on to a vast and elaborate narrative fresco.

Does the aforementioned quip tell us any more about Angelopoulos and his cinema? Could it also suggest that he is perhaps no longer considered the great European visionary he once was? Or possibly that his grandiose mythical parables require such concentration, willingness and openness from their audience that they could never be consumed as simple entertainment. In a 2006 review of Eternity and a Day (Mia eoniotita ke mia mera) in The Village Voice, critic Michael Atkinson shrewdly compared Angelopoulos’s trail-blazing innovations of cinematic syntax to those of Thomas Pynchon in the field of literature: work to marvel at rather than relish. The Greek director remains an icon of the so-called Slow Cinema movement – a feared enclave that includes Andrei Tarkovsky, Miklós Janscó, Béla Tarr, Chantal Akerman and Hou Hsiao-Hsien among its most esteemed devotees. On a giant platter of ‘cultural vegetables’, Angelopoulos’s films would undoubtedly be seen by most people as the brussels sprouts.

Ulysses’ Gaze, courtesy Kobal Collection

The 1990s were when Angelopoulos was at the peak of his considerable powers. The intoxicating but much mocked Ulysses’ Gaze (To vlemma tou Odyssea) was awarded a Special Jury Prize at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival, but much to Angelopoulos’s public chagrin, it was pipped at the post for the Palme d’Or by another tale of moral and geographical decomposition in the Balkans – Emir Kusturica’s Underground. Three years later, Angelopoulos nabbed the Palme with Eternity and a Day, a typically multifaceted and elegiac exploration of a terminally ill poet (Bruno Ganz) who chooses to embark on an ad hoc journey across Greece – and achieves spiritual enlightenment via an encounter with an Albanian orphan.

Angelopoulos is often cited as the auteur’s auteur, the justification being that you can enter any one of his 13 features at any juncture and his vehemently languid style – weather-beaten yet ornate, primitive yet profound, bombastic yet intimate, real yet surreal – will be instantly recognisable. This theory can now be put to the test, as every one of his films is receiving a UK release on DVD – from his remarkably assured monochrome feature debut Reconstruction (Anaparastasi, 1970) right through to his most recent feature The Dust of Time (I skoni tou hronou, 2008), which has never been released theatrically in the UK.

Speaking to the 76-year-old Angelopoulos over the phone from his production office in Athens, I am impressed that all his films remain indelibly etched on his memory, even though he insists he never rewatches them once they have been completed. I ask him about the first shot of his first film, Reconstruction – a rural policier that doubles as a lamentation on Greek cultural decline (one could see it as the mirror opposite to a film like Elia Kazan’s melodramatic 1963 emigration saga America, America). It’s a long take of a bus pulling up on a muddy road next to a hillside village. Some people get off the bus and start trudging up the hill. I wonder if he realised that even with that first shot, he was breaking new stylistic and intellectual ground? “When you start making films, you’re acutely aware of convention,” he says. “Though personally I find that you don’t choose the method in which you make a film. You are the one who is chosen.

“For the first sequence shot in Reconstruction, I remember the cameraman asking me how long the take needed to be,” he continues. “As the camera rolled, I closed my eyes. I listened to the sounds being made by the actors. I could hear their breathing and their footsteps. When it sounded right I said, ‘Stop.’ And it was perfect. The timing of these shots is not something I choose. These shots are not protracted in any way. Each shot is simply as long as it needs to be. It’s more of an instinct rather than a choice. When I devise these shots, I have to choose whether I give in to the things I see with my own eyes. Then I must decide if it’s worth intervening with the landscape in some way to fit with my initial dream.”

Angelopoulos has been likened to a kind of orchestral conductor more than a conventional film director – a suggestion he resists. “I’d describe myself as a translator,” he says. “A translator of a sound, a feeling and a time that comes from far away. When it comes to me, I have no choice but to absorb it.”

The characters in an Angelopoulos film are nearly always on the move. Their journeys and their interactions with landscape and the displaced flotsam and jetsam of the roadside are central to what his films are about. Look at Marcello Mastroianni’s crestfallen turn in The Beekeeper (O melissokomos, 1986), as he crystallises his dislocation from the younger generation while transporting a cargo of bees across the country for the spring. Or look at the pre-teen brother and sister on a paradoxical search for a mythical father figure in the extraordinary Landscape in the Mist (Topio stin omichli, 1988).

“The only place I really feel at home is in a car next to a driver,” the director admits. “I don’t drive myself, but I find the simple act of passing through landscapes very moving. The way I look at the world on my various travels is what essentially defines my filmmaking.” And what of the village in Reconstruction? Did his damning prophecy of decline come true? “Recently I met with a female director and we visited the village in the north-west of Greece where Reconstruction was filmed. Back then, people were leaving and going to Germany to work. When I returned it was very different. The place had become more commercialised. Despite its problems, there used to be a poetic authenticity to the town and its people which is no longer there.”

Systems of symbols

Angelopoulos has been heralded as one of the great chroniclers of 20th-century Greek history, though his ideas are never baldly stated, evolving instead through fragile systems of symbols and careful visual and aural juxtapositions. Made during the rule of the right-wing military junta, The Travelling Players was a film that forced Angelopoulos to think innovatively. “It’s what we called ‘the fear of intervention’ – the fear that our artistic expression would be corrupted,” he explains. “The threat of censorship makes filmmakers function in a completely different way. When I think about the film now, I feel The Travelling Players is a name that could also refer to the crew making the film. The technicians and the actors got in trouble with the police. A couple of them spent some time in prison. Even more important than the role of the director was the person we had as a lookout to make sure there were no military police in the area.”

It was partly this “fear of intervention” that led Angelopoulos to employ a symbolist mode of filmmaking. “The Travelling Players is probably not the obvious example, because half of it was filmed after the regime. It just meant that we filmed all the things that would have been censored or illegal after the regime had toppled,” he says. The key film in this process, for him, was the earlier Days of ’36 (I meres tou 36, 1972), about the far-flung ramifications of a prison siege in which an incarcerated informant and assassin is held at gunpoint by a conservative politician.

“Days of ’36 refers to the Metaxas dictatorship of 1936 and was filmed during the dictatorship of the 1970s,” he explains. “It was with this film that I had to change the way I spoke as a filmmaker. Everything became suggested or implied. When Days of ’36 was first shown in Athens, there were people in the audience who started asking questions. I was surprised when I realised that those people weren’t the police. I remember one woman handed me some flowers and asked: had she really understood everything she had just seen? And of course I said yes. In the spirit of the film, even this dialogue with the audience was suggested and implied.”

Part of the fascination of Angelopoulos’s cinema is knowing that the spectacle you’re watching was actually staged for the camera. Witnessing the giant statue of Lenin transported downriver in Ulysses’ Gaze is as genuinely awe-inspiring as any celluloid chicanery by Spielberg or Lucas. Such set pieces are a glory to behold, recalling such silent showmen as Lang, Griffith or von Stroheim. (Incidentally, Angelopoulos admits to being very fond of Michel Hazanavicius’s silent-cinema homage The Artist. “It piqued my memories,” he says. “It was when I first saw the silent classics that I knew I wanted to make films myself.”)

It’s almost impossible to imagine money being made available to carry out such logistical feats for the camera today – particularly given Greece’s ravaged economy. But Angelopoulos insists he will never be tempted to turn to computer-generated imagery as a means to an end. “If I choose to have a similar shot to the one in Ulysses’ Gaze in my new film, it will be filmed in exactly the same way,” he says. “I don’t make films just to try and achieve something. It’s the experience that counts – the process. It’s about how the scene is formulated. It’s giving birth to the image that matters to me.” A 3D feature is clearly out of the question, then? He laughs: “It’s not something that has been put forward to me. I’d say that my conception of what cinema is could not be married with this method.”

Cycle of reprocessing

Angelopoulos’s highly principled method of image making has clearly been an influence on many contemporary film directors. Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once upon a Time in Anatolia boasts that Angelopoulos touch, as does Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le quattro volte. How does he feel when he sees a film that has clearly been informed by his style? “Every generation is influenced by the previous one,” he concedes. “It’s a cycle of reprocessing – of handing ideas down through time. If ever I see a film where there’s a long sequence shot, or an idea I’d recognise from my own films, I just remember that I was influenced – possibly unconsciously – by the generation of filmmakers before me, and they would probably have had the same reaction if they were watching my films.”

Despite an economy in tatters, Greek cinema is in fine fettle at the moment, with young, spiky talents in the form of Yorgos Lanthimos (Dogtooth) and Athina Rachel Tsangari (Attenberg) wowing (and occasionally scandalising) audiences worldwide. “I find these films very interesting indeed,” says Angelopoulos. “There is a new generation of filmmakers in Greece. They’ve created a new language and they have something to say. It’s very different to the so-called New Greek Cinema of the 70s, and it’s good to see that after all these years there’s another groundswell of creative activity.”

While he’s enthusiastic about Greece’s cinema, he’s less inclined to see hope in its political future. In an interview he gave around the time of 1991’s The Suspended Step of the Stork (To meteoro vima tou pelargou) – arguably his most directly political work – he was quoted as saying that he’d always considered politics as a faith; now he saw it as a profession. “I’d say that notion is still relevant,” he says now. “Serving people is a job, not an ideology.” As stories of Greece’s economic decline hog the front pages, I ask Angelopoulos if he feels his films have regained a political prescience.

“In a strange way I do,” he admits. “But I do not for a moment think this is a good thing. Everything back then that looked like a series of bleak possibilities for our future is now being confirmed. I come from a generation where we thought we were going to change the world. Back around 2000 was when it felt like the dream was over.”

His next film, The Other Sea, is the closing chapter of a trilogy, and will be “based on the political realities of the now, both here in Greece and across Europe”. The first film of the three, The Weeping Meadow (To livadi pou dakryzei, 2004) deals with the construction and maintenance of a riverside village in 1919. The second, The Dust of Time, is a creatively executed game of temporal hopscotch, in which a film director (played by Willem Dafoe) wrestles with his family history while searching Europe for his missing daughter. While these two films are set in the past, The Other Sea dwells on the present and the future.

“The end of The Dust of Time is also the end of a dream,” Angelopoulos explains. “This new film is about the lack of a dream at the moment. I don’t think the problems of the present are necessarily financial problems, but a general lack of values. This new film talks about a closed horizon. As a country, it’s like we’re all sitting in a closed waiting room, and we have no idea what’s going to happen when that door is finally opened.”

‘The Theo Angelopoulos Collection’ volumes 1-3 are out now on DVD

See also

Miklos Jancsco: cinema’s lost language reviewed by Jonathan Romney (January 2012)

Songs for swinging lovers: Tony Rayns on Hou Hsiao Hsien’s Three Times (August 2006)

Cinema at the crossroads: James Bell reports on Theo Angelopoulos and Kazakhstan’s Eurasia film festival (January 2006)

Trilogy: The Weeping Meadow reviewed by Nick Roddick (January 2005)

Werckmeister Harmonies reviewed by Jonathan Romney (April 2003)

Keeping a distance: Janet Bergstrom on Chantal Akerman’s innovations (November 1999)

Eternity and a Day reviewed by John Mount (June 1999)

Black Cat, White Cat reviewed by John Wrathall (May 1999)

Stalker reviewed by Gilbert Adair (Winter 1980/81)