Primary navigation

The films of Mizoguchi Kenji combine detachment with intense emotional involvement, argues Brad Stevens

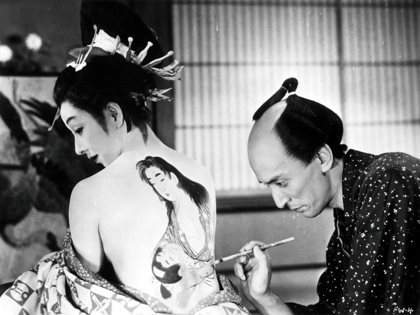

The Mizoguchi Collection: Osaka Elegy / Sisters of the Gion / The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (pictured above) / Utamaro and His Five Women

Mizoguchi Kenji; Japan 1936/36/39/46; Artificial Eye / Region B Blu-ray / Region 2 DVD; Certificate PG; 406 minutes total; Aspect Ratio 1.33:1

Of all the directors for whom greatness can be claimed, few have proved so difficult to pigeonhole as Mizoguchi Kenji, whose cinema combines the outward with the inward, movement with stillness, Kurosawa’s violent action with Ozu’s meditative contemplation, whose mise en scène uses long tracking shots that have all the elegance of Ophuls but tend to focus on events that are anything but elegant. Most significant of these (real or apparent) contradictions is the characteristic tone of Mizoguchi’s films, in which intense identification is imbricated with critical detachment.

Mizoguchi’s main concern is with the theatrical nature of both masculinity and femininity – a concern especially relevant to a patriarchal culture where gender roles are rigidly policed. The notion of theatre as a metaphor for behaviour in a conformist society is frequently literalised in the form of theatrical performances. An especially neat example can be found in Osaka Elegy (1936) when Ayako (Yamada Isuzu) and her employer Sonosuke (Shiganoya Benkei) visit a bunraku (puppet) theatre and unexpectedly encounter Sonosuke’s wife Sumiko (Umemura Yoko), who accuses her husband of infidelity. Mizoguchi uses shots of puppets performing on stage to comment ironically on the theatrical aspects of both the illicit affair and the resulting argument, something underlined when Sumiko is told not to “make a scene”, and Fujino (Shindo Eitaro), on being asked to pretend that Ayako came with him, complains that “it’s a ridiculous role to play” (though Artificial Eye’s subtitles translate this as: “That’s a terrible position to be put in”).

But theatricality is also evident when Ayako tells her potential fiancé Susumu (Hara Kensaku) that she has been Sonosuke’s mistress. Mizoguchi stages this as a two-minute sequence shot with Ayako occupying various areas in the frame’s rear and Susumu standing in the foreground at screen left: Ayako’s speech is thus directed at both Susumu and the audience/camera, with Susumu functioning as our surrogate (since we can only see his back, he might be another viewer watching the onscreen events with us). But the fact that we can’t see Susumu’s face means that we, like Ayako (who delivers most of her speech while facing away from Susumu), are left wondering what his response will be to the confession. As so often in Mizoguchi, identification is split between more than one character, thus allowing us to consider from a detached perspective events with which we are involved emotionally. When Ayako withdraws even further from Susumu, and addresses some comments (“If I keep going on like this, I don’t know how far I’ll fall. When I think about it, I feel sorry for myself”) to a window in the extreme background of the image, is her gesture theatrical or spontaneous? Is it even possible to make a distinction between the two?

Utamaro and His Five Women – or Five Women Around Utamaro

Until recently, Mizoguchi was poorly represented on DVD, so the appearance of this four-disc set from Artificial Eye (who have already given us discs of The Lady of Musashino and The Life of Oharu), alongside Masters of Cinema’s four double-bills (themselves now available as a single box-set) and Criterion/Eclipse’s Fallen Women collection, is most welcome. Whereas Masters of Cinema focused on Mizoguchi’s later work, three of the four titles newly released by Artificial Eye in both standard and Blu-ray formats – Osaka Elegy, Sisters of the Gion (both 1936) and The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939) – are taken from that period in the second half of the 1930s when the director was exploring radical and feminist politics. The seemingly odd film out here is Utamaro and His Five Women (1946), made under quite different conditions, during America’s occupation of Japan.

The connections between the two titles from 1936, both of which star Yamada Isuzu (and can also be found in Eclipse’s set), are obvious, and have been well analysed by Mark Le Fanu in Mizoguchi and Japan (BFI, 2005) and Robin Wood in Sexual Politics and Narrative Film (Columbia University Press, 1998). As Wood observed, Osaka Elegy is “as single-mindedly dedicated to the analysis of the oppression of women within the family as Sisters of the Gion is beyond it, to the extent that each film seems to necessitate the other”.

But if these two films form a kind of diptych, the same might also be said of Chrysanthemums and Utamaro, which both use male protagonists to express their feminist concerns: although the central character in each film is an acclaimed male artist – Kabuki actor Kikunosuke (Hanayagi Shotaro) in the former, painter Utamaro Kitagama (Bando Minosuke) in the latter – Mizoguchi’s emphasis is on the women around them who can only express their own creativity by supporting and inspiring the men (a process viewed with bitter irony in Chrysanthemums, in which Kikunosuke achieves fame by playing women on stage). In this context, it is unfortunate that Artificial Eye’s DVD of Utamaro has been packaged under the American title, which, as Jonathan Rosenbaum argued in Monthly Film Bulletin in December 1976, is “misleading and offensive”: the Japanese title can more correctly be translated as Five Women Around Utamaro.

Artificial Eye’s transfers are as good as the source materials allow. Chrysanthemums has never looked better, though that’s not saying much: the image, while sharp and clear, is frequently obscured by shimmering. The subtitles are vastly superior to those on the print screened at the Barbican in London in 2010 (in which the kabuki scenes were untranslated). The Blu-ray editions make the picture grain far more evident, to the extent that darker sequences in Osaka Elegy and Sisters of the Gion seem to be taking place behind a lace curtain: ironically, the cheaper DVDs provide a more satisfying viewing experience.

Silent Naruse reviewed by Brad Stevens (June 2011)

The Water Magician reviewed by Alexander Jacoby (October 2010)

Artist of the floating world: Alexander Jacoby on Mizoguchi’s contemporary films (April 2008)