Primary navigation

The early films of Japanese master Naruse Mikio reveal a conflicted relationship with modernity, says Brad Stevens

Flunky, Work Hard / No Blood Relation / Apart from You / Every-Night Dreams / Street Without End

Naruse Mikio; Japan 1931/32/33/33/34; Criterion/Eclipse Region 1; 28/79/60/65/88 minutes; Features: new scores by Robin Holcomb and Wayne Horvitz, sleeve notes by Michael Koresky

The Criterion Collection is renowned for its lavish DVDs, filled to overflowing with meticulously assembled extras. Its sister label Eclipse was started in order to release barebones collections of films not considered worthy of such treatment, but this supporting act has now become more interesting than the main show. For me, Eclipse’s latest box-set, ’Silent Naruse’, is its finest yet.

For many years, Naruse Mikio has been something of a legend among western aficionados of Japanese cinema. He was, we were frequently informed, one of the cinematic masters, yet his large body of work (89 films, of which 22 are lost) was virtually invisible outside Japan. This situation has thankfully now changed, thanks to several retrospectives, DVD box-sets issued by Masters of Cinema and the BFI, and the efforts of file-sharing websites whose members have created English subtitles for the bulk of Naruse’s oeuvre.

Given the sheer weight of expectations that accompanied our belated exposure to Naruse, it would hardly be surprising if we had initially found his work something of a disappointment. On the contrary, many cinephiles now regard him as fully the equal of Mizoguchi and Ozu. Perhaps the reason Naruse has taken so long to arrive on foreign shores is that his style isn’t immediately identifiable: though he shares Mizoguchi and Ozu’s concern with women attempting to define themselves in the face of patriarchal oppression, his mise en scène has more in common with that of such self-effacing American classicists as Howard Hawks and Leo McCarey. Indeed, it’s possible to watch Naruse’s films without being consciously aware of style as such – which perhaps explains why exposure in international arthouse markets, where overt visual styles are seen as handy promotional tools, has been so long delayed.

Which isn’t to say that there are no identifiably Narusian stylistics. One of the director’s favourite images involves two people walking and talking while the camera tracks to follow them from a slightly frontal position (there are early examples of this in No Blood Relation and Street Without End). Naruse was always happiest when observing personalities and societies in states of transition (he functioned just as effectively in the war and occupation periods as he did during times of supposedly greater freedom), and his tracking shots privilege conversationalists who, far from being trapped inside their own solipsistic viewpoints, actively engage with the person they’re speaking to, the sense of growth and change these individuals are capable of conveyed by the camera’s constant forward movement (scenes in which characters fail to engage in this way are shot in a quite different style, usually as a series of isolated close-ups). It is this sense of dynamic progression that distinguishes Naruse’s finest films.

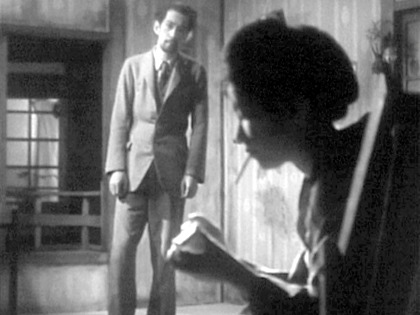

Every-Night Dreams (1933, also pictured at top)

Eclipse’s collection contains all five of Naruse’s surviving silents (19 titles from this period, including the director’s first seven films, are no longer extant), the earliest of which, a short with the wonderful title Flunky, Work Hard (1931), also contains the first known example of those traffic accidents that appear throughout the oeuvre and can be found in three of the other films collected here, No Blood Relation (1932), Every-Night Dreams (1933) and Street Without End (1934).

These often fatal collisions provide the best evidence of Naruse’s conflicted relationship with that modern world represented by cars and trains. Apart from You (1933) is the only film in this set whose characters are not laid low by moving vehicles, but it still uses forms of transport to demonstrate Naruse’s ambiguous attitude towards modernity (the main concern of Catherine Russell’s indispensable book The Cinema of Naruse Mikio: Women and Japanese Modernity). An early scene shows a teenager named Yoshio lying by a railway line as trains, those indispensable representatives of progress, move across the screen in the background, suggesting the dreams of escape in which this truant is indulging. Later, Yoshio and the young geisha Terugiku take a train to visit the latter’s parents in a harbour village, where they talk by the sea (boats, emblems of a more traditional Japan, float motionlessly in the background) and Terugiku expresses her desire to “go somewhere far away” – a wish both realised and cruelly undermined by the film’s climax, in which she is obliged to catch a train that will take her ‘far away’ to an unspecified location where she will endure a life of prostitution.

Unsurprisingly, the condition of the five prints is highly variable, with Flunky, Work Hard and No Blood Relation showing obvious signs of damage, but on the whole the picture quality is quite satisfactory. The films have newly recorded scores by Robin Holcomb and Wayne Horvitz which are appropriately understated. It is to be hoped that Eclipse will eventually release more Naruse anthologies: in an oeuvre so full of masterpieces, it’s hard to single out individual titles deserving of release, but it would be especially nice to see the sublime Husband and Wife (1953), as well as some of the director’s underrated comedies, such as Five Men in the Circus (1935), Travelling Actors (1940) and Conduct Report on Professor Ishinaka (1950).

Takamine Hideko, 1924-2010 remembered by James Bell (February 2011)

The Water Magician: Alexander Jacoby on a rare screening of Mizoguchi’s first signature work (November 2010)

Ozu Yasujiro, tofu maker: Tony Rayns on the Japanese master’s cinematic diversity (February 2010)

Mizoguchi Kenji: artist of the floating world: Alexander Jacoby on Mizoguchi’s lesser-known contemporary films (April 2008)

Still Walking reviewed by Trevor Johnston (February 2010)