Review / From the archives

The Last Picture Show

Movie references or no, Peter Bogdanovich’s bittersweet portrait of small-town disenchantment offers a universal depiction of the workings of nostalgia, as Tom Milne wrote in his 1972 Monthly Film Bulletin review

The Last Picture Show

USA 1971

Director: Peter Bogdanovich

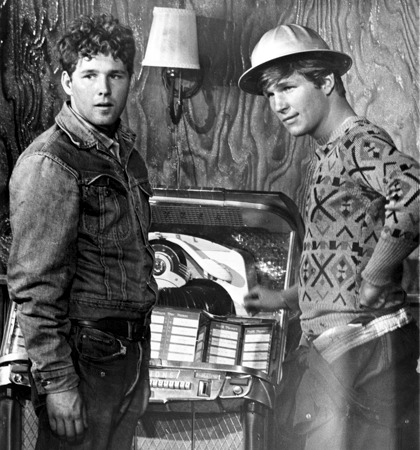

With Timothy Bottoms, Jeff Bridges, Cybill Shepherd, Ben Johnson, Cloris Leachman, Ellen Burstyn, Eileen Brennan

126 mins (restored version) | Cert 15

Synopsis

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

1951, in the dreary little Texan town of Anarene. With few excitements on hand apart from the weekly picture show, sex is the main preoccupation for Sonny Crawford in his last year in high school. Having just broken with his unprepossessing steady, Charlene, he enviously eyes his friend Duane, who seems to be making good progress with the glamorous Jacy. But while Sonny finds himself enjoying a tender affair with Ruth Popper, the football coach’s tired, neglected wife, Duane has trouble with Jacy, who abandons him at a Christmas dance to attend a nude swimming party where she meets the rich and dashing Bobby Sheen. Furious, Duane instigates a silly joke on a dumb boy, Billy, with the result that Sonny falls foul of Sam the Lion, owner of the local cinema, pool-hall and café, and surrogate father to both Sonny and Billy. The breach is eventually healed, but returning from a jaunt to Mexico with Duane, Sonny is shocked to learn that Sam has died suddenly.

Graduation day arrives. Shortly after, Jacy finally lets Duane sleep with her – because Bobby Sheen prefers girls who are not virgins – and walks out on him only to find that Bobby is getting married. Duane leaves town, and Jacy, after an unhappy interlude with her mother’s lover Abilene, coaxes Sonny away from Ruth Popper. Nothing happens between them but Duane, returning for a weekend, picks a fight with Sonny, who is hospitalised. When he recovers, Jacy, thrilled because the affair is the talk of the town, persuades Sonny to marry her, making sure her parents know in time to rescue her and pack her off to college. Duane joins the army, and spends his last night in Anarene, before embarking for Korea, with Sonny at the last picture show before the cinema closes down. Sonny, now running the pool-hall left him by Sam, sees Billy killed by a passing truck, and in his loneliness goes back to Ruth for consolation.

Review

Starting with a bleak, windswept street, dead leaves mingling with the dust and Minnelli’s Father of the Bride on show at the dilapidated little cinema on the corner, The Last Picture Show ends with precisely the same scene, the only difference being that the film posters have now disappeared for ever. To Bogdanovich, as a movie buff (one of the more fatuous bits of incidental information about the film is that he “walked about in pants worn by John Wayne in Three Godfathers”), this is clearly very symbolic: “I got very excited by the notion of doing an early Fifties period piece and exploring the change the came with the demise of the small-town movie house and the introduction of television. A whole kind of dream world ended and a lot of other illusions began breaking up.”

Whether that “dream world” has really ended, and whether the “breaking up” of those “other illusions” was in any way connected with the death of Hollywood, is highly debatable; but the point is that, as with Targets, where Bogdanovich discussed a very interesting film in very suspect (not to say jejune) terms as being about the connections between old Karloff and new mad-sniper styles of horror, he seems to be the worst advocate for his own excellent work. So much so that one begins to wonder how much Polly Platt (designer on both films and involved in the script of the first) contributed to them, considering that the real key to both Targets and The Last Picture Show is the way they reflect their themes visually: the spotlessly hygienic, soulless suburbia of glass, concrete and fresh white paint that turns the all-American boy into a mad sniper in Targets; the grey, faceless sameness of the peeling walls, the cracked windows, the fading shop-signs, the houses all looking as though they had been furnished by the same tasteless computer, that leaves Sonny stranded in his despairing emptiness at the end of The Last Picture Show.

To say this is not to denigrate Bogdanovich’s direction (anyone who can handle actors as he does, so that it is difficult to know where to stop in listing the really outstanding performances – Cloris Leachman, Ben Johnson, Timothy Bottoms, Eileen Brennan, et al. – is no mean talent) so much as to suggest that he may be doing the right things for the wrong reasons. For despite the fact that it is set with hallucinating exactness in Texas and in 1951, with the right clothes, the right cars, the right music, the right words, even the right hairdos, all pinned down like specimens on a drawing-board in Robert Surtees’ bleakly nostalgic black-and-white photography, this story of the disparity between dreams and reality, of lost illusions and the abandonment of hope, might have been set anywhere at any time.

Of course the fact that it is set so accurately in one particular place and time is what makes the film good; what makes it rather more than good – even better, perhaps, than Malle’s Le Souffle au Coeur, which matches it in all other respects – is that it swallows up its own rather facile symbolism (the cut, for instance, from the dismal reality of Charlene in the cinema removing her chewing-gum before kissing Sonny, to the dream-factory image of the young Elizabeth Taylor on the screen) in the circular structure which contrives to suggest that history, as always, is busy repeating itself. Sam the Lion may lament the good old days when he didn’t have to leave town to breathe fresh air; and he may once have known an Anarene where the cattle roamed the prairie (as in the clip from Red River we are shown) instead of speeding through herded in trucks; but his dream of past glories is essentially no different from the one Sonny will have once his present and slightly sordid experiences have acquired the distant, nostalgic glow of time. Sam talks dreamily about the girl he loved whom he used to take swimming in the nude in the lake; and while we, the audience, remember the similar but less edifying episode involving Jacy and Bobby Sheen, Sonny listens in awe to the romantic fantasy, never imagining for a minute that he himself may have lived a similar moment in his second visit to Ruth Popper’s bedroom, picnicking on the floor with this tired, middle-aged woman miraculously transformed by happiness into a laughing girl.

“I guess if it wasn’t for Sam I’d just about have missed it, whatever it is,” says Lois Farrow, the girl Sam was remembering, now a tolerably sluttish mother barely speaking to her husband and coolly advising her schoolgirl daughter to lose her virginity. For Sonny, that “whatever it is”, waiting to be enshrined by memory, is almost everything he experiences in the film, everyone who made him feel special and out of the ordinary for a moment: Sam the Lion, Ruth, Billy, the picture show, even perhaps Duane and Jacy. It is, in a sense, the town of Anarene itself, spread out before us bleak and hopeless and characterless, yet already transformed by time just as the raw realities of the old West have been metamorphosed with the years into the romantic dreams of Hawks, Ford and the great westerns.

Tom Milne, Monthly Film Bulletin, April 1972

Peter Bogdanovich discusses the restored version of ‘The Last Picture Show’ with James Bell on page 11 of the May 2011 issue of Sight & Sound.

‘The Last Picture Show’ is re-released from 15 April 2011 at the BFI Southbank and venues around the UK

See also

Slim and the silver fox: David Thomson on Howard Hawks’ screen fantasies of his relationship with his second wife Nancy (February 2011)

One for the road: David Thomson on Bob Rafelson’s masterpiece Five Easy Pieces (September 2010)

Giant Steps: David Thomson on the mavericks of the 1970s’ New Hollywood (September 2006)

Lonesome cowboys: Roger Clarke on Brokeback Mountain (January 2006)