Out of the darkness: Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams

As his first 3D film Cave of Forgotten Dreams reaches our screens, Werner Herzog talks to Samuel Wigley about primitive man, albino crocodiles and the ethics of 3D

With typical perversity on the part of Werner Herzog, his first (and likely only) foray into 3D forsakes the pulsing immensities of ocean and cosmos – the bread and butter of three-dimensional documentary-making – for the restrictive murk of a cave in the South of France.

Discovered in 1994, the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave contains the oldest known artworks in the world – pictures of bears, cattle, lions and bison painted on to the cavern walls by early man some 32,000 years ago. Sealed off by rockfall, this prehistoric gallery survived unseen and untarnished for millennia. Even now, its rarefied atmosphere is too fragile to allow public access; the cave hosts an ultra-exclusive private view to which only a select few scientists are invited. All of which sounds like a red rag to a bull for a director like Herzog, whose reputation for filming in far-flung and insurance-policy-voiding conditions needs no introduction – and who claims to have been so possessed by a book he saw at the age of 12 featuring a Lascaux cave painting on its cover that he got a job as a ball boy solely to save up for it. By unique arrangement with the French government, Herzog and a crew of three were granted access to Chauvet – a privilege denied even Judith Thurman, the journalist whose article in The New Yorker first piqued the interest of Herzog’s producer Erik Nelson.

Last spring, film critic Roger Ebert wrote a polemic in Newsweek entitled ‘Why I Hate 3D’, in which he nonetheless conceded interest in what a filmmaker of Herzog’s vision might do with the format, adding that Herzog had promised him that in Cave of Forgotten Dreams “nothing would ‘approach’ the audience”. Herzog hasn’t exactly kept to that pledge: one scene involving a spear sends up the tawdry tactics of 3D cinema even as it has us dodging it in our seat.

But Ebert was right to be optimistic that Herzog would also light out for less banal territory. His third dimension gives a reach-out-and-touch physicality to the contours and cavities of the stony canvases, bringing us as close as we’ll ever be allowed to get to works that – as Herzog reasons – evince the awakening of the soul of man.

Samuel Wigley: How did you go about persuading the French government to allow you access to the Chauvet Cave, where others had failed?

Werner Herzog: Let’s say it was a quest of some complexity, because the French are usually territorial when it comes to their patrimony. I was very lucky because the French minister of culture, Frédéric Mitterrand, turned out to be a great fan of my films. When I met him, I was just about to explain my project when he asked to have the first word and for ten minutes spoke about how deeply moved he had been by my films. So [I was] like the little girl in the fairytale who opens her apron and golden stars fall into her lap.

Did he talk about any of your films in particular?

He knew my films from very, very early on, and he said he even interviewed me once for French television! I said, “Monsieur le ministre, I do not remember.” There was then a straightforward attitude that I would work as an employee of the Ministry of Culture. I would ask for €1 as my fee, and the French government could use the film in 40,000 classrooms in France – everything non-commercial, everything in perpetuity, for no money, for nothing. So there was a proposal that apparently made sense to the French government. But of course there’s more than just the Ministry of Culture, there’s also a regional government that has to give its OK, and then there is the curator, the custodian of the cave delegated by the scientists… So it took a while. I think my enthusiasm was kind of convincing, otherwise I wouldn’t have made the film.

They imposed a lot of restrictions on you while you were shooting inside the cave.

Yes sure, but understandably so. You see, from the first moment of this cave’s discovery, the three discoverers did everything right. They sealed the cave instantly. They would only move [around in there] by rolling out and walking on a strip of plastic foil – every single step was done right.

You have to see it in the light of other caves, like the famous cave of Lascaux, which had to be locked down completely because too many tourists went in and left mould growing on the wall from their human exhalations. The same happened to a famous cave in Spain, Altamira. So these restrictions are completely understandable. You do not step off a metal walkway that is two feet wide, because when you step off there are human footprints 32,000 years old and charcoal and whatever other forms of evidence – the cave was completely hermetically sealed for tens of thousands of years.

How did you find the atmosphere inside the cave? There were toxic gases.

You do not sense the CO2 gas, but after an hour or so you feel woozy. There are guards with you and they keep measuring the level of toxic gas and make sure they move you out soon enough. There are safety precautions, gas masks and oxygen tanks, all sorts of things. In another part of the cave is a fairly high concentration of radon gas – this has a cumulative effect, so you don’t stay too long.

What was your reaction to seeing the paintings for the first time?

Well, stunned! Completely and utterly stunned. I had seen photographs – there are two books of photos out. I had some idea what I was going to see. But seeing it in there, in this silence where you can hear your own heartbeat, is really, really something very special. And besides, two things caught me unawares: I had no idea how beautiful the cave was, with all its stalagmites and stalactites, nor how many bones there were – 4,000 bones, mostly from cave bears.

You describe these paintings as representing the awakening of the modern human soul.

It seems to be evident, because at the same time [they were painted] you still had Neanderthal men roaming this area. And Neanderthal men never created culture: there were no burials; there was apparently no religious belief system. Here you clearly have hints of first religious belief systems. You have figurative representation of animals, of humans. There is evidence of musical instruments. There is evidence of body adornments. And, of course, technical inventions like the spear thrower, which was invented some 15,000 years before the bow and arrow – extraordinary inventions that Neanderthal man didn’t have. So it’s quite, quite evident that it is us. It is us 32,000 to 35,000 years ago.

Of course we have no idea what the paintings meant to them. We can only take some educated guess by looking into cultures that were in a Stone Age existence until fairly recently, like Australian Aborigines or bushmen in the Kalahari Desert.

I was particularly struck by how multi-dimensional the paintings are.

I like that you saw it in 3D, because I keep saying this film is the only 3D film where I really know it was imperative to do it in 3D. I was and I still am a sceptic of 3D, but the moment I saw the cave it was absolutely clear it had to be done in 3D, no question, no discussion about it.

It must have been difficult using the camera in that confined space.

The steel door was hermetically sealed behind us – they didn’t want to open and close the door all the time because the climate inside is so delicate. I was only allowed three people with me, and so on this two-foot-wide walkway we had to reconfigure our camera from scratch. We started out with literally a steel plate with holes and two parallel steel rods for the two eyes, or the two lenses. I had very, very excellent people: cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger and his assistant Erik Söllner, a very, very good craftsman. And we were blessed that we had Kaspar Callas, a man from Estonia, who not only developed some of our software but built our hardware as well! Just a phenomenal, phenomenal talent. He’s also a filmmaker, so what was good [was that] I never talked to a technician – I spoke to a fellow filmmaker.

Have other 3D movies inspired you?

No, not really. There is not much inspiration [to be had] from 3D films, and I can tell you why. Number one, our eyes are not really comfortable with seeing 3D over lengthy periods of time. We see the world with one eye dominant and the other one peripherally seeing the third dimension. Of course, when you’re a basketball player in the NBA you have to use full 3D throughout the game to understand the movement of people, the ball and the position of the target. But it’s not very comfortable and the brain is very selective, so it somehow dims down our 3D vision in everyday life. So it’s fine for when you do real ‘fireworks’ like some of the 3D films [do], like Avatar, yes, it’s OK. But 3D is not going to take over everything, like from black-and-white television to colour television. It’s not going to happen like that…

I have developed a dictum, but I have to explain it first. When you see a firework, there’s nothing beyond the firework effect. There’s no depth to it, there’s no deeper meaning to it. When you see a romantic comedy, for example, we as an audience live and develop through a parallel story – we hope and pray that our young lovers should, against all obstacles, find each other by the end. In 3D you only have what is in 3D and nothing beyond – it’s a very strange effect. And hence, this is my dictum: you can shoot a porno film in 3D, but you cannot film a romantic comedy in 3D.

The format is perfect for bringing out the contours of the cave, but you also seem to be having some fun with the format, notably with the scene in which a spear is thrust towards the camera.

Yes, I’m making some fun of the 3D effect, sure.

The other interesting thing is that you’re bringing what is seen to be one of the most cutting-edge forms of cinema to what is the most primitive form of cinema, as you refer to cave painting in the film.

There’s something like proto-cinema in some of the paintings, like a running bison with eight legs, somehow hinting at movement, and a rhinoceros in seven or eight phases, like in an animated film, [seen] bit by bit by bit. It’s quite astonishing.

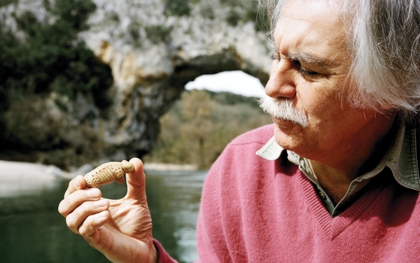

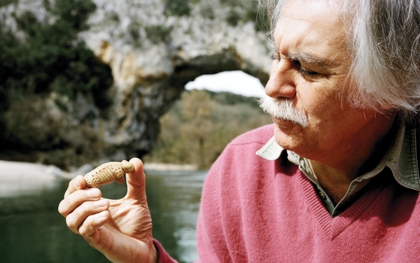

How did you find Maurice Maurin, the master perfumer who appears in the film?

I was searching for him. I learned that there are plans to build a replica of the cave for tourists, about three miles away, and I was told that there are even plans to recreate the prehistoric scent of the cave. I got in touch with this perfumer lady who wanted to speak in front of the camera, [but] she was unreliable and not really good on film.

So I was searching for a perfumer and by coincidence, only 20 miles away, there lived this perfumer who used to be the president of the Master Perfumers of France. He was just wonderful and I loved his enthusiasm and his way of talking. But of course I asked him to sniff out cracks in the rock and describe the scent emanating from it.

And how did you discover the albino crocodiles featured at the end of the film? These reptiles seem to link back not only to the iguanas in Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans but all the way back to the lizard specialist in Fata Morgana (1971).

They are wonderful. They happened to be not too far away, on the Rhône river, near a nuclear plant. I didn’t even know they were albino crocodiles – I went there because I was just curious to see the 300 or more crocodiles. Right next to the entrance there’s this separate enclosure and I saw these two albino crocodiles – I could not believe my eyes and I said, “They have to be in the movie.”

It’s pure science fiction, but of course related to the film. How do we see images that were made 32,000 years ago? How would an albino crocodile see images by human beings? Very, very strange, and for me a very deep question, of course. And, strangely enough, the film speaks about [the fact that] the site is widening and soon these crocodiles will reach Chauvet Cave and penetrate it – only four months ago a handful of crocodiles escaped from this compound. They were all recaptured with the exception of one, which is still at large somewhere in the French countryside. I really love that idea.

At one point you describe the scientists’ digital mapping of the cave as akin to drawing up the Manhattan telephone directory. Were you frustrated by the experts’ more clinical, pragmatic approach?

No, thank God there is a new generation of scientists who are very diligent in describing the status quo and who are not like the previous generations in immediately declaring this as a cult site. They are much more cautious. I think it’s quite good that they are mapping, and then after that they try to understand the stories behind it. They are very cautious in their assessments.

A long time ago I made a film – one of my first films – The Flying Doctors of East Africa [1969]. Villagers in Uganda were taught about preventing trachoma and eye disease, and for two years they were teaching using posters. I had the feeling the villagers did not see them the way we saw them, and I asked: “What is this here?” (An eye.) They said, “This is the rising sun,” though for two hours they had been taught about this eye and how to clean it. And I asked, “Can you show me a single eye?” Some people pointed at windows of a hut. I had the feeling I should dig deeper into this, and I hung four posters parallel to each other and, on purpose, I hung one upside down. On camera, I explained to the villagers: “I have four posters here. You have seen these posters all day long, and I have hung one upside down on purpose. If you were suspended by your feet by a rope and your head was dangling down, which one of the four posters would be upside down?” Less than half could identify the poster that was upside down. They probably saw some abstract specks of colour. They must have seen the image in a different way to the way we saw it.

Until today I have had no idea how they were seeing it. I have tried to explore the procedure of human vision: how would we know what these animals in the paintings on the walls meant for humans that were 32,000 years ago? It was a time when Neanderthal men were roaming around, a time when the Alps were covered by 9,000 feet of ice, when you could walk from Paris to London with dry feet because the ice absorbed so much humidity that the English Channel didn’t exist. So, how do we understand, beyond such an abyss of time, what was going on in [their minds]?

We also have to speculate that there might have been cannibalism, because in all Palaeolithic and Neolithic cultures you have evidence of it. When for them did the human being start to exist? It’s an interesting question, because you find skeleton remains of babies with the garbage, but children who were over three years old were buried. So, human toddlers, who did not speak yet, apparently for them didn’t yet have human nature. So there are very deep questions about human beings who are, in a way, us, and yet separated by an abyss of time. In other words, I’m glad that there is a new generation of archaeologists out there.

I know you usually work very closely with the musicians scoring your films. What sort of instructions did you give Ernst Reijseger for his music?

I showed him materials as quickly as I could – long, long takes of images that I had filmed, uncut. He immediately understood and proposed that there should be a choir and an organ. We recorded in a church and I was always there during the recording. In a way I was also guiding the inner ductus of the music. There was one piece that was too motorik in its rhythm and I said, “No, this is not going to work, we have to have it slower. It has to flow, it has to float.” We have an intense rapport when he’s recording music. I love Reijseger. In my opinion, he’s of the calibre of a young, emerging Stravinsky. You will not easily find music of that calibre in a film in the next few decades.

Assuming you’re not tempted by the idea of making a narrative film in 3D, can I ask what you are working on at the moment?

On Monday I will continue filming on death row, first in Florida and then in Texas, for a film project, Death Row. It will be a one-and-half-hour documentary, but I’m also planning to make four separate one-hour films on individual cases. And I’m working on a feature-film project, which is a sort of big epic in the Arabian desert. And I have some five or six other feature films pushing at me, lining up. And I will hold my Rogue Film School, by the way, in London in March. I’m viewing DVDs and applications at the moment. I like what I do.

‘Cave of Forgotten Dreams’ is released on 25 March, and is reviewed in the April 2011 issue of Sight & Sound

See also

Les enfants terribles: Gaspar Noé and Harmony Korine discuss 3D and other matters (October 2010)

Venice 2009: Jonathan Romney reports on the premieres of Herzog’s Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans and My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? (September 2009)

Stars in his eyes: David Lynch talks to James Bell about his musical collaboration Dark Night of the Soul, the possibilities of 3D and other matters (July 2009)

Invincible reviewed by Richard Falcon (April 2002)

The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas reviewed by Amanda Lipman (September 2000)

Battlefield Earth reviewed by Kim Newman (July 2000)

The 13th Warrior reviewed by Kim Newman (September 1999)