Film of the month: Submarine

Unlike so many other British TV comedians who have made the transition to film directing, Richard Ayoade reveals a distinctive cinematic talent with his debut, the skewed teen romance Submarine. By Isabel Stevens

Too precocious. Not believable. That was The New Yorker’s assessment of Holden Caulfield 60 years ago when they rejected The Catcher in the Rye in story form. We know now that they overlooked two things: that the mundane details of pubescence often benefit from enhancement, and that self-involved teens in possession of a skewed but perceptive outlook and a singular vocabulary have a knack of talking their way into our hearts.

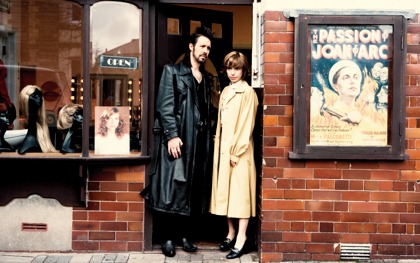

With Richard Ayoade’s Submarine, 15-year-old dictionary reader Oliver Tate becomes the first British adolescent to join the likes of Max Fischer, Harold Chasen, Ferris Bueller, Tracy Flick and Juno MacGuff in cinema’s register of larger-than-life, idiosyncratic teens – coming as he does from Swansea rather than Hollywood. But in some ways Oliver is a familiar subject for a coming-of-age tale: a briefcase-and-duffel-coat-sporting geek who realises his dreams of getting a girlfriend and losing his virginity – one of those awkward but erudite-behind-the-scenes types who would run a mile from the drug and alcohol-fuelled kids in Skins (and whom you suspect Caulfield would call a phony for the close attention he pays to the playground hierarchy).

Through Oliver, Ayoade channels a lot of the characteristics he himself displayed as Moss, the computer nerd he plays so delectably in Channel 4’s The IT Crowd. But like his kindred spirit Max Fischer (from Wes Anderson’s Rushmore, 1998), Oliver isn’t a wallflower but a first-class schemer with ambitions to single-handedly save his parents’ marriage, rescuing his mum Jill (Sally Hawkins) from the clutches of her ex-flame, spiritual guru Graham Purvis (Paddy Considine), and his dad, marine biologist Lloyd (Noah Taylor), from depression. He’s also trying to get his relationship with Jordana (Yasmin Paige) back on track after her mother develops an untimely brain tumour that keeps getting in the way of their love life. As you might have guessed, Submarine – like Rushmore – is very funny largely because of its protagonist’s staggering capacity for self-delusion.

Like the eccentric, hyperactive teenage mind into which Submarine torpedoes us, Ayoade’s film – his feature debut – barely rests, darting between Oliver’s everyday routine and his memories, fantasies, fears, oddball observations and quasi-philosophical musings. There may be limits to how much precocity an audience will tolerate, but Ayoade’s highly subjective approach makes us care more for the pompous Oliver than we might otherwise.

Cliché dictates that, in typical teen film fare, the object of a geek’s affection should be either another female of the species or else the polar opposite, an unattainable goddess. Here, however, the girl is an emotion-hating pyromaniac with a yen for blackmail, herself only marginally more popular than the boy; in one great scene under a railway bridge, Jordana stands with a cigarette in her hand and a smirk on her lips, ordering Oliver to his knees.

It’s not unusual for British TV comedians to graduate to directing feature films, but Submarine is very much a fully fledged feature rather than just an extended comedy sketch show; it’s also an adaptation that works even better on screen than the source novel did on page. Though Ayoade preserves Oliver’s interior monologue from Joe Dunthorne’s 2008 book, he capitalises on cinema’s objective faculties to undermine Oliver’s fantastical views on his new relationship – focusing, for instance, on Jordana’s scrunched-up face as Oliver attempts a sloppy post-coital kiss.

Throughout, the deadpan approach to acting rules – especially for the excellent Craig Roberts, whose facial muscles are hardly flexed at all, except for the slight smile Oliver wears after he loses his virginity. This isn’t, however, as distancing an effect as it might be; whether Oliver is horrified by the thought of Graham and his mum together or simply trying to trip his parents up with hypothetical questions, the emphasis stays on his big, brown puppy-dog eyes. Yet ultimately it’s less Oliver’s charm that wins us over than that of the film itself. Oliver may start off as Jordana’s plaything, but soon young love is being celebrated with fireworks and sunsets shot in such coy soft focus they feel like memories, each one accompanied by one of Alex Turner’s wispy, delicate tunes. All of which could, of course, come across as rather corny, but Swansea’s industrial backdrop (combined with Jordana’s hatred of anything romantic) keeps the sentiment at bay.

Still, a heady nostalgia pervades this tale of bygone teenage years. Ayoade transports the noughties Oliver of Dunthorne’s novel back to a time when teenagers had to pass notes in class, and communication was more direct and painful (without Facebook or email, Oliver has to resort to scrawling on his hand the reasons why Jordana should sleep with him). Indeed, with all the typewriters, Polaroids, super-8 footage and other near-obsolete technologies on display, Submarine feels like an ode to old analogue ways. Crocodile Dundee is in the cinemas, we’re told, but the only other obvious period details are Graham Purvis’s over-gelled mullet and his New Age self-promotional videos. Purvis’s “mystic bullshit” light-show may terrify Oliver, but Ayoade revels in it, indulging the soft spot for gloriously cheesy 1980s effects he’s shown in past directorial work (music videos for the likes of Vampire Weekend and Super Furry Animals, as well as the TV spoof Garth Marenghi’s Dark Place).

Similarities between the titular horror author Garth Marenghi and Submarine’s Graham reveal Ayoade’s other passion: lampooning smarmy, self-satisfied twits. With Oliver he strikes a balance: he’s not a teenage Alan Partridge, more a younger version of High Fidelity’s list-loving Rob or Peep Show anorak Mark. But with Graham there’s no restraint. Paddy Considine has a lot of fun with the caricature (and gets some killer lines), but it’s noticeable that Ayoade’s adults aren’t quite as well developed as his teenagers. Sally Hawkins manages admirably to bring a sense of reality to her portrayal of Oliver’s uptight mother, but – apart from some eloquent musing on depression by Oliver – Noah Taylor’s sad face and droopy eyes are the only real clue to how father Lloyd is feeling. (In Rushmore’s Herman Blume, Anderson created a far more convincing world-weary parent.) Despite this, Submarine has some lovely observations on adulthood – as any film about teenagers should. “When you grow up, your heart dies,” is the aphorism voiced by the articulate loner in The Breakfast Club (1985). But for Jordana and Oliver, the opposite is true: growing up is when you go gooey in the middle and no longer want to burn someone’s leg hair.

With its off-kilter stance, split-screen antics and musical interludes, Submarine feels very indebted to the Wes Anderson template of filmmaking, though Ayoade does temper his wackiness with the real particulars of teenage life (classroom banter, Jordana’s eczema). When we see Oliver desolate over the loss of his girlfriend, his kindred spirit isn’t so much Max Fischer as the forlorn, clueless Gregory in Gregory’s Girl (1981). But Ayoade can be just as sly and self-conscious as Anderson when he wants to be. Submarine is littered with references to the nouvelle vague (from beaches and bicycles to the Ma nuit chez Maud poster on Oliver’s bedroom wall), and takes full advantage of cinema’s repertoire of jump cuts, zooms and freeze frames. But Ayoade’s not just being playful for the sake of it. When Jordana and Oliver first lock lips, Oliver is so happy he keeps his eyes open, and the camera too is so excited it jumps about all over the place; for their second kiss, Ayoade does a slow 360-degree turn, savouring the moment.

For in the end, like the most successful forays into adolescent existence, Submarine doesn’t quite feel like it’s made by a grown up.

Richard Ayoade talks about his cinematic influences on page 45 of the April 2011 issue of Sight & Sound

See also

The April 2011 issue: In defence of Woody Allen, and more (March 2011)

He stands alone: Martine Pierquin on Jean Eustache, travelling companion of the French New Wave (November 2009)

On a wing and a lark: Shane Meadows talks to Nick Bradshaw about improvising Le Donk and Scor-Zay-Zee with Paddy Considine(October 2009)

Afterschool reviewed by Lisa Mullen (September 2009)

The New Wave at 50: Riding the wave: six renowned directors on what the nouvelle vague meant to them (May 2009)

A Room for Romeo Brass reviewed by Mark Kermode (February 2000)

Gregory’s Two Girls reviewed by Edward Lawrenson (December 1999)

Rushmore reviewed by Richard Kelly (September 1999)