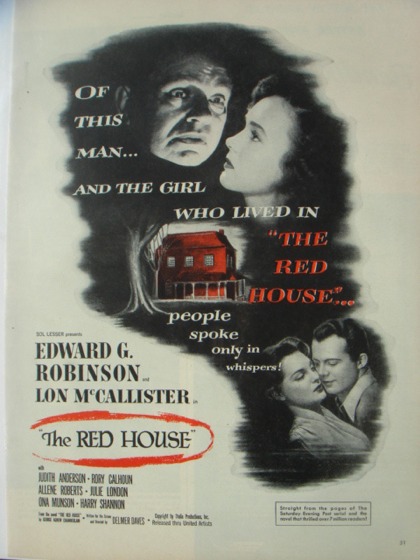

Lost and found: The Red House

Filmmaker Charles Burnett remembers the thrills, disturbances and subdued rage of The Red House

I must have seen The Red House (1946) first on television, some time in the 1950s. I was a young boy at the time and it left a lasting impression on me. I’d not seen a film before that was so disturbing – I’d seen horror films, but nothing that was so psychologically effective. I can’t understand why it’s not shown more in film classes, why it’s not better appreciated. Delmer Daves was a very good director.

The film is set up at the beginning almost like a Grimm fairytale – ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ or ‘Hansel and Gretel’. It opens in beautiful countryside, a small-town American idyll. It’s a sunny day. The kids are on the school bus. A voiceover tells us that it was once a place covered by dense forest, but no longer – the land has been tamed by civilisation, light has entered and penetrated the darkness. Everywhere, that is, except for the Oxhead woods, which are criss-crossed with dead-end trails and an abandoned road that leads only to the Morgan farm, a place like a walled castle that everybody knows about but few have entered. It reminds me of a book that I like very much by Stanton Forbes called Grieve for the Past, which is also about a house that holds dark secrets, and which starts with a lovely poem. It’s as though just behind the small-town idyll, hidden in the woods, down these paths that lead nobody knows where, is the big bad secret everybody carries.

It’s one of the best-written mystery movies I can think of, because it all seems so real and natural. It has more than just one-dimensional characters, and reminds me of Jean Renoir’s The Southerner in that respect. Edward G. Robinson plays one-legged farmer Pete Morgan, who lives with his sister Ellen (Judith Anderson) and a girl named Meg (Allene Roberts), who they have raised as their own, telling Meg that her own parents died down south looking for work during the Depression. Meg’s now a teenager and interested in boys – in particular Nath Storm (Lon McCallister), who she’s after despite his going out with the school sexpot Tibby (Julie London). Meg persuades Pete to employ Nath as a farmhand over the summer, and it leads to a web of long-buried secrets being forced out. At dinner at the end of his first day on the farm, Nath tells them that people in town whisper gossip about what really happened to Meg’s parents. When Nath tells Pete he plans to take a shortcut home through the Oxhead woods, Pete warns him not to, because of “the screams from the Red House that will lodge in your bones all your life”. The Red House is an abandoned building even deeper in the woods, and Nath and Meg decide to find it and uncover what happened there years ago.

If you grew up in a small town like that, you know there’s a lot going on under the surface. They seem idyllic, but in reality they’re some of the most disturbing places of all. David Lynch brought that contradiction out brilliantly in Blue Velvet, but in the mid-1940s how much was that shown on screens? Film noirs of the time have perversities running through them, but here it’s so close to the surface.

It’s also very frank about sex for its time. In one scene Teller (Rory Calhoun), who Pete employs to watch over the woods and keep people away from the Red House, tells Tibby: “I’m good at things they don’t teach at school.” This non-prudish attitude is healthy – it’s suppressing things, like Pete, that leads to sickness.

Edward G. Robinson does such a good job of conveying his character’s twisted inside. I’ve seen him in gangster films, but here he is more than just an actor – it is like he is a person in the room with you, which is very scary. He has a protective shell about him, but deep down he has this secret, that thing that makes you feel ambivalent towards him. Is he good or bad… or what? Towards the end, Ellen tells Meg, “You must pity Pete.” Ellen and Pete’s relationship is disturbing because it’s so suggestive of incest, but her comment is sympathetic, as it suggests Pete is as much a victim as he is a monster, because he’s carried these haunting memories all his life.

I was also very impressed by Rory Calhoun. He plays this hired hand, but not as the typical backward hillbilly who you might find in, say, Deliverance. People in the film have these grey areas. When Tibby, this very sexy girl, falls for him – which doesn’t seem like it should happen because Nath is the hero – you can understand it because he’s this strong, attractive guy. Your sympathies are pulled between the characters in ways you wouldn’t expect.

Miklós Rózsa’s score really adds to the sense of anxiety. He was a great composer who did Spellbound with Hitchcock. In the scene when Nath first goes into the woods, the wind becomes a gale and the music suddenly swells and turns deafening and dramatic, and in amongst the strings Rózsa uses a theremin. It’s this sound that you associate with sci-fi, and yet here it is in this rural thriller.

There are several scenes that have stayed in my memory. One of the most haunting is when Pete stands on a wooden jetty, Meg swims towards him and he calls her “Jeanie”, which is the name of the woman he loved – Meg’s mother. It’s horrifying and at the same time tragic.

Someone really needs to do a restoration of the film. It’s on DVD, but the picture and the sound are so bad that they don’t do justice to the Rózsa score, or to Bert Glennon’s black-and-white cinematography. I wish I could see it on the big screen.

There are different interpretations of the film: you could see the Red House as being like the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, making Pete do what he did. It’s almost supernatural. At one point Pete turns and says, “There’s a curse in these woods.” But I see it as though he’s tormented by the crime he committed and he’s in denial, trying to project it on to something else. He’ll blame anything but himself, his jealousies, his rage.

It’s a strange film to have seen as a boy, because it’s about a man who has carried dark secrets with him all his life, and seeing it again today I might take different things from it. It’s like when you’re a kid listening to the blues and you haven’t had the experiences those guys are singing about yet; you might like it for other reasons – the sound, the rhythm of the song – but not the lyrics, because you’ve not got there yet. Later, when you’ve experienced life a bit, you can appreciate it more. You can say: “Now I understand what he’s singing about. What anger is when it’s unresolved.”

Charles Burnett was speaking to James Bell. His films include Killer of Sheep, The Glass Shield and Nightjohn

What the papers said

“An interesting psychological thriller, with its mood sustained throughout… however, [it] has too slow a pace, so that the paucity of incident and action stands out…, despite good performances”

— Variety, December 1946

“Warped relationships are the norm in this weird but hardly wonderful world… It’s a pastoral, noir-inflected psychodrama with supernatural overtones, dealing chiefly with the thin line between healthy and sick sexuality. All very Freudian, in fact, and often very frightening, with Edward G. Robinson in superb form as the patriarch tormented by his past”

— Geoff Andrew, Time Out

See also

Lost and found index

Gangsters special, part 3: Thunder roads: Michael Atkinson on movie gangsters and the American Dream (August 2009)

The New Wave at 50: Riding the wave: Charles Burnett and five other renowned directors on what the nouvelle vague meant to them (May 2009)

The Woodsman reviewed by Philip Kemp (February 2005)

Be black and buy: Ed Guerrero on the shifting sands of African-American independent cinema (December 2000)

Death and the maidens: Graham Fuller on Sophia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (April 2000)

Resident phantoms: Jonathan Romney looks for clues to Stanley Kubrick’s themes in The Shining’s Overlook Hotel (September 1999)