Primary navigation

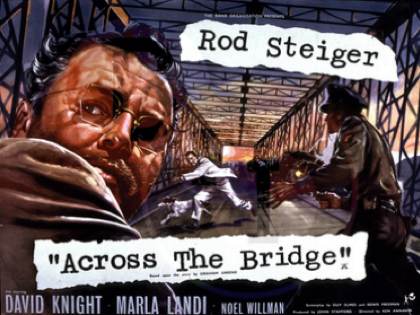

A model of adaptation, Across the Bridge cleverly expands Graham Greene’s original short story, says the screenwriter Paul Mayersberg

The screenplay of Across the Bridge (1957) was, the director Ken Annakin has said, largely the work of Guy Elmes (1920-1998). It is a superb film and a master lesson in the vaguely criminal craft of film adaptation. Graham Greene’s 1938 short story consists of the observations and guesswork of an unnamed narrator about a crooked fugitive financier named Joseph Calloway in a small town on the Texas-Mexico border, where he is planning to escape across the bridge between the two countries. He is a wretched, venal character whose only sign of humanity is his grudging affection for a stray dog. Cynical in the extreme, Greene concludes: “Only one more indication of a human being’s capacity for self-deception, our baseless optimism that is so much more appalling than our despair.”

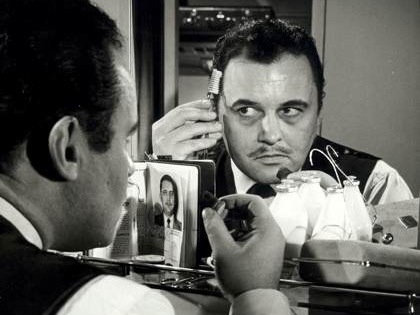

In the film the Englishman Calloway becomes Carl Schaffner, a German with a British passport, played by an American (Rod Steiger). (The name Calloway had also been used for the Trevor Howard character in The Third Man where, in a reversal of identity, he was the hunter of a criminal on the run.) We meet Schaffner in his London office, making his desperate escape before arrest, aiming for Mexico, from where he cannot be extradited. This scene is not in Greene’s story. While the situation may look forward to Enron-Madoff models of our time, Steiger has the demeanour of a Nazi war criminal on the run, an echo of Orson Welles’s character in The Stranger (1946).

Schaffner takes a train to avoid being on an air passenger list. Crossing America he meets, by chance or destiny, a man with the not dissimilar name Scarff (Bill Nagy), whom he murders on impulse to steal his identity. This scene is not in the story either, yet it is as Greene-like as anything Greene wrote. Steiger and Nagy’s flawless performances mirror each other, while Annakin’s Hitchcockian editing gives the murder and disposal of the body a sensuality that looks forward to Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley’s Game, as filmed by Liliana Cavani in 2002, with John Malkovich (another neglected work).

When Schaffner arrives at the border town, he finds that Scarff is also a wanted man on the run – again, a twist not in the original story. The homosexual duality explicit in Highsmith and Hitchcock, covert in Welles and Joseph Cotten in The Third Man, forms no part of Steiger’s performance; Schaffner’s wife has, we learn, committed suicide. Steiger conveys an uncontrollable erotic power born of frustration, greed and revenge; he’s a man who possesses and devours people – which may be the subversive impulse in writers who are drawn to the subject of identity theft.

When I saw the film at the age of 16, the seed may have been sown for my protagonist in Croupier (1997): a man who writes his own double life, stealing from other characters as he goes, to become one of the thieving cheats he despises. I have long been intrigued by films that make us complicit with criminals.

While the plots of identity-swap films – mostly spy stories and comedies – are inevitably similar, the performances of the actors in them can be very different. Perhaps because of their divided personae, they seem to become their own rewriters. When Schaffner arrives at the town, he finds it already peopled with characters as corrupt as he. Outwardly uneasy, he is actually at home in this Dante-esque purgatory. Seldom has a town in the sun felt so dark. Orson Welles might perhaps have played Schaffner more sympathetically than Steiger but with less truth – had he not been too busy that year in his own border town in Touch of Evil. Steiger’s Schaffner is a cousin of Harry Lime, trying and failing to escape his no man’s land by bridge instead of by sewer.

Parallels with The Passenger (1974) have been remarked on, and it’s possible that film’s English screenwriters, Mark Peploe and Peter Wollen, had seen Annakin’s film. But whereas Antonioni’s road movie seems to dream Jack Nicholson as the reporter of uncertainty, hovering between sleep and waking, Across the Bridge has Rod Steiger kick, bully and cheat his own narrative, powerful and powerless at the same time. Steiger gives the film an expressionist feel uncharacteristic of English movies at the time.

Shot in Spain, Across the Bridge has an atmosphere of alienation, with an American lead, an Italian lady (Marla Landi), a Canadian (David Knight) and English actors like Noel Willman playing Mexicans, not always convincingly; there’s a whiff of post-war European cinema about it, Italian in its obliviousness to nationalities.

The true female lead, indeed the love interest, arrives without a passport as a dog named Dolores, owned by the dead Scarff, adopted reluctantly by Schaffner to preserve his new identity. Referred to in the story as “the hateful dog”, Dolores is a brilliant departure. A sweet femme fatale who saves Schaffner’s life by waking him in the presence of a deadly scorpion, she becomes both his physical nemesis and his human salvation. Related to the old man’s dog, Flick, in Umberto D. (1952), Dolores is also an heir to the friend of the hunted Jean Gabin in Quai des brumes (1938), where it is the master who lives and dies like a dog. Scarff must have had a vestige of good in him, which through Dolores is transferred to Schaffner – an optimistic variation on the Hitchcockian transference of guilt. Across the Bridge is a fully realised vision – a haunted, sorrowful pattern of a world gone to the bad.

So why did the film disappear? It was a commercial success for Rank at the time, and got excellent notices. Perhaps it was because Annakin was not seen as an auteur; perhaps because Steiger was an actor not a star; or perhaps it simply slipped through the revival net. Happily Across the Bridge is now available as a DVD on the ITV label, but it really deserves to be seen on the big screen.

A year earlier Annakin had directed Loser Takes All, scripted by Greene himself, and before that Elmes had co-written The Stranger’s Hand (Mario Soldati, 1954) from a Greene treatment – with Trevor Howard and Alida Valli, no less! All those bridges: magpie writers and directors like to call it borrowing, whereas they are really stealing from their other selves.

Paul Mayersberg’s screenplays include ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’ (1976), ‘Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence’ (1983), ‘Eureka’ (1983) and ‘Croupier’ (1997)

“Annakin’s direction has seldom been so competent, though the Clouzot-like relish he brings to the more unpleasant scenes is sometimes disturbing. He seems to have been able to do little to subdue Rod Steiger, whose performance is as studied, self-conscious and contrived as the script.”

— Derek Hill, Sight & Sound, Autumn 1957

“Some English critics regard [Across the Bridge] as their best thriller since The Third Man. If the film had sustained the tension of its opening scenes the comparison might be apt, but the middle of the picture… falls apart.”

— Pauline Kael, from 5001 Nights at the Movies