Primary navigation

Robert Breer’s lifelong experiments with film intrigue Ian Francis

“Please be aware of your immediate surroundings at all times,” reads a laminated card at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art’s Robert Breer exhibition in Gateshead. It’s the work of a health-and-safety official made sleepless by Breer’s motion sculptures (or ‘floats’), an armada of blobs, pillars and walls that roam the gallery at less than snail’s pace, keeping invigilators and visitors on their toes. It’d serve just as well as a motto for Breer, an artist who hoovers up the minutiae of the world around him – and whose work makes us continually conscious of our own watching.

Born in Detroit into a family of engineers, Breer escaped to Paris and a foray into abstract expressionism in the late 1940s. Soon impatient with working on canvas, he looked for an open end beyond the ‘absolute statement’ of painting; thanks to a Bolex borrowed from his cine-enthusiast father, he found it in film. The early series of Form Phases (1952-54) marshals blocks and lines around the screen in a clunky dance that never fully resolves itself, always butting at the edges of the frame or creating new frames. Thus began Breer’s 50-year filmmaking journey, littered with innovations and gear changes, but always somehow retaining the self-taught simplicity of those early experiments.

The essential ingredient is an endless supply of 6”x4” index cards, the canvas for sequences of doodles and patterns that can be dashed off in the studio or out and about (Breer has been known to knock up a temporary lightbox in his hotel room using a drawer and a sheet of glass). During the editing process he makes sense – and nonsense – of these sequences, shuffling the cards and varying the pace to create a cascade of images that will occasionally promise to settle before flying off in another direction. There is a rare nod to plot in the title of A Man and His Dog out for Air (1957), but only towards the end do the eponymous characters materialise – and even then they are constantly in danger of turning into something else.

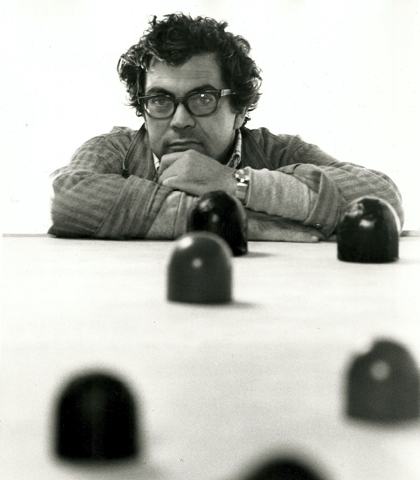

A Breer ‘float’ in the Baltic

This world of constant metamorphosis can be traced back to animation pioneers such as Winsor McCay, Max Fleischer and Emile Cohl, filmmakers high on the transformative power of the medium and unwilling to tether their characters to reality. (Breer is also a big fan of Jean Vigo, who shared his hungry eye and love of chaos.) Breer would claim that he ended up in a similar place simply by working out techniques from scratch; his main wellspring of inspiration has always been the optical trickery of pre-cinema, manifested at the Baltic by a series of flip-books and Mutoscopes that are just begging to be cranked into life. The pleasure lies not just in the tactile but in the foregrounding of cinema’s mechanics: “The hat should be transparent and show the rabbit.”

Breer’s challenge is to the continual forward locomotion of cinema (“It’s a delusion to think that we’re getting anywhere”), and to the visual homogeneity that story can create by picking out particular figures within the frame. To get anything from a single-frame barrage such as Recreation (1956) or Fist Fight (1964), we have to let go and just look. Stan Brakhage was a contemporary, and in some respects they aimed for the same ocular enrichment (or Eyewash, as one of Breer’s titles has it). The visual was paramount, and both were wary of diluting the image with sound. But while most of Brakhage’s films are made to be viewed in reverent silence, Breer worried that the total absence of sound would put the viewer on edge. If you stand in the middle of his exhibition you will hear a fluctuating aural stew of musique concrète, squawking chickens, Dadaist poetry and radio noise.

While tugging playfully against the images, these home-recorded soundtracks also tend to root the films in the world they emerge from. After periods of geometry, cartooning and collage, Breer developed a stronger autobiographical slant to his work during the 1970s. Always interested in jumping between two and three dimensions, he was able to blur the boundaries further after his discovery of rotoscoping, which allowed him to turn cine footage into impressionistic sketches.

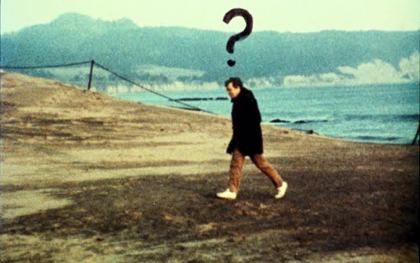

Bang!

Move up to the second floor of the gallery and you’re confronted by the floats, another of Breer’s strategies for keeping things fresh. Starting out with little styrofoam blocks that patrolled New York happenings in the mid-1960s, Breer ended up creating a fleet of huge fibreglass domes for the Pepsi Pavilion at Osaka’s World Exposition in 1970. For Breer they offered another level of open-endedness beyond painting and film – and a chance to exercise his engineering nous.

Around the edges of the exhibition you can see his later films, restless blazes of colour and ideas increasingly concerned with home, family and memory. Death pops up on a regular basis, in the form of a derailed train, a spinning gravestone, or – in Bang! (1986) – a very self-conscious fade to black. “WHAZZAT? FADE OUT?” comes the riposte. One thing is clear: Breer is still resisting the forward march towards oblivion.

The Robert Breer exhibition is at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, until 25 September. Eight of Breer’s films can be viewed online at Ubuweb.

Love Letters and Live Wires Highlights from the GPO Film Unit reviewed by Michael Brooke (November 2008)

Animation special: an animation timeline (August 2006)

The thin black line: Harvey Deneroff on the pioneering animation techniques of the Fleischer brothers (June 1999)

The innovators 1900-1910: Charles Musser on the editing achievements of Edwin S. Porter (March 1999)