Primary navigation

Banderas’s doctor in The Skin I Live In is only the latest in the movies’ proud heritage of gothic medics. By Kim Newman

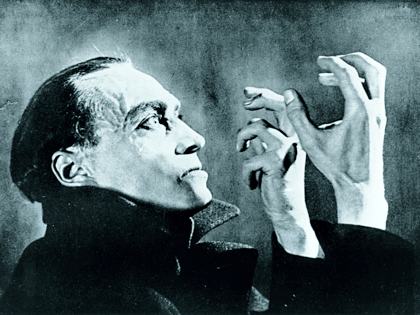

In 1924 Robert Wiene filmed Maurice Renard’s novel The Hands of Orlac, casting Conrad Veidt (above) as the concert pianist who’s worried that the new hands grafted on to his stumps after a railway accident are those of a guillotined murderer – and that the alien fingers’ impulse to strangle will override his wish to perform sonatas. When Karl Freund remade the film in Hollywood as Mad Love (1935), the emphasis changed, with the angst-ridden patient (Colin Clive) now upstaged by the flamboyant surgeon Dr Gogol (Peter Lorre) who performs the operation.

The progress of medical science has always inspired the gothic imagination. Renard’s story has been remade several times, and inspired dozens of spin-offs about transplanted body parts which perhaps retain the souls of their original owners: the penis of Percy (1971), the body parts of Body Parts (1991), the heart of Heart (1997), the eyes of The Eye (2002). Dr Gogol, meanwhile, is in a line of descent that includes Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (another role for Colin Clive in James Whale’s 1931 film) and H.G. Wells’s Dr Moreau (most memorably incarnated on screen by Charles Laughton as a whip-wielding sadist in 1932’s Island of Lost Souls).

The Hands of Orlac, and a whole genre of surgical horrors that followed, draws on such tabloid-friendly crazes as the procurement of anatomical specimens through body-snatching (Burke and Hare and their descdendants recur in the cinema), the especially-hateful-to-British-sensibilities practice of vivisection of animals to advance the cause of knowledge (Moreau’s cruel treatment of dumb beasts is his prime sin) and the turn-of-the-century quackery of rejuvenation through the implanting of monkey glands (as in the Sherlock Holmes story ‘The Adventure of the Creeping Man’, and a clutch of comic monkey-gland caper films in the teens).

Mad Love

In films, Frankenstein and Moreau are condemned for ‘trespassing in God’s domain’ – which the staunchly atheist Shelley and Wells would have regarded as a gross misreading of their respective works – and their projects do ultimately seem to serve little purpose beyond illustrating human inadequacies. In the wake of World War One, however, attitudes even to mad science changed and the lab-coated lunatics of the 1930s at least pay lip service to helping humanity by reviving the dead (see The Walking Dead, 1936; The Man They Could Not Hang, 1939; Man Made Monster, 1941) or enabling crippled, mutilated or disfigured patients – scarcely in short supply during and after the war – to ‘live normal lives’. Somehow, this means that schemes intended to help cute little paraplegic girls walk again entail Boris Karloff dressing up as a gorilla to murder folk for their cerebrospinal fluid in The Ape (1940), which is actually one of the more grounded, reasonable mad-doctor quickies of its era. The tinkerer-with-flesh recently featured in The Human Centipede (2009), who sews three people together mouth-to-anus, would scarcely be out of place set beside the characters played by Karloff, Bela Lugosi, George Zucco, Lionel Atwill or John Carradine in the heyday of Hollywood horror.

Lugosi’s Dr Vollin in The Raven (1935) is an even more demented genius than Lorre’s Dr Gogol, but he is also one of several movie plastic surgeons (see also Let ’Em Have It, 1935; Dark Passage, 1947; Jailbait, 1954) who operate unethically to alter the recognisable faces of wanted criminals. “Maybe if a man is ugly, he does ugly things,” muses Vollin’s latest on-the-run customer (Boris Karloff), inspiring the doctor to deliberately disfigure the man (though he is still recognisably Karloff) so he can have a ruthless minion on hand. A modest reverse of this process is tried in Walter Hill’s Johnny Handsome (1989), in which a freakish crook (Mickey Rourke) turns his life around when surgery performed in prison makes him look normal, whereupon he sets out for revenge on those who have mistreated him. These days, however, cosmetic surgery has become such a mainstay of the Hollywood lifestyle that American films tend to touch on it only in throwaway jokes about hideous beautiful people (see Just Go with It, 2011), or to show the temptation a doctor who might be useful and poor in the sticks faces as a moneyed Beverly Hills face-fixer (Doc Hollywood, 1991).

Face/Off

Even if George Cukor’s A Woman’s Face (1941) suggests that losing a facial scar can also enable a female crook (Joan Crawford) to escape evil influences, there’s a queasy suggestion that the result is still some sort of monster. This notion is elaborated in many crossbreeds of horror and melodrama, including the films that most obviously shape Almodóvar’s approach to the subject in The Skin I Live In: Terence Fisher’s Stolen Face (1952), in which Paul Henreid reconfigures a Blitz-scarred petty crook as the image of the girl he can’t get (Lizabeth Scott); Sidney Hayers’s remarkably lurid Circus of Horrors (1960), with Anton Diffring reshaping scarred criminals as beautiful performers, before mutilating them all over again; and of course Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1960), with Edith Scob in a distinctive white mask, endlessly recreated by her surgeon father.

Face swapping eventually reached the big-budget Hollywood mainstream with Face/Off (1997). But it was Jesús Franco’s Franju rip-off The Awful Dr Orlof (1962) that brought the subject to Spain. Franco (who returned to the theme in 1987’s Faceless) may be Spain’s most maudit auteur, but Almodóvar – for all his arthouse cachet – is clearly conversant with his work: in Matador he even uses clips from Franco’s 1981 film Bloody Moon.

Restoration heaven: Jonathan Rosenbaum on the Il Cinema Ritrovato archive-film fesitval (July 2011)

The Atrocity Exhibition reviewed by Tim Lucas (August 2006)

Border control: Edward Buscombe on Once Upon a Time in Mexico (October 2003)

An eye for an eye: Nick James on Minority Report (August 2002)

The cage of reason: Kim Newman on Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow (January 2000)

Jock of gold: Shawn Levy on producer Don Simpson’s invention of the modern blockbuster (December 1999)

Silicone And Sentiment: Paul Julian Smith on All About My Mother (September 1999)

The Mummy reviewed by Kim Newman (July 1999)

Gods and Monsters reviewed by Kevin Jackson (April 1999)