Primary navigation

David Thompson remembers his youthful discovery of Station Six Sahara and the unfulfilled promise of its director, Seth Holt

We probably all remember movies from our childhood that marked us in some way. One shot from one film has never left me: a near-naked Carroll Baker sitting in a chair in the middle of a desert, watched by a group of heavily perspiring men. The all-important detail was that her bra straps were hanging down her arms. I must have been about 11 or 12 when I saw it. Need I say more?

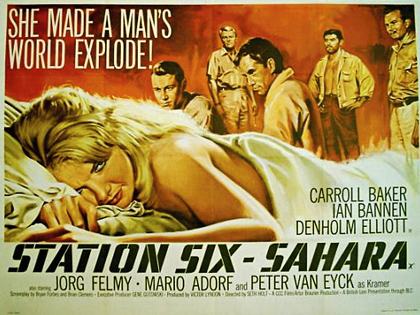

I’m certain I saw this particular film on television. Somehow I eventually discovered that it was none other than Station Six Sahara, a British-German co-production first released in 1963. I remembered little of the film except for this one provocative image (though that almost seemed enough). But when would I be able to see it again?

Cut to 1986, when I had the opportunity to programme my first season at the National Film Theatre, a complete Martin Scorsese retrospective. To spice it up, I added films that had influenced him, as well as throwing in a few titles he had included in that entertaining ‘Guilty Pleasures’ column in Film Comment magazine. Happily for me, among them was Station Six Sahara. As Scorsese wrote: “Here you get that palpable sense of being in a place – stuck in a place. And you learn what it’s like in a society of people who live on the outside. Way on the outside.”

The film all takes place on an oil station somewhere in the Sahara (it was actually shot close to Tripoli), where the pumps are manned by a motley crew. We’re introduced to them as a newcomer arrives – a taciturn, self-disciplined German (Hansjörg Felmy). Ominously, he’s driven to the station in a truck that also carries the coffin in which his predecessor will be taken away. Once there, he encounters a raucous, ribald Scot (Ian Bannen), an uptight, snobbish English former army major (Denholm Elliott) and a shy, uncommunicative Spaniard (Mario Adorf). All are under the thumb of their boss (Peter van Eyck), a proud, isolated figure who prefers to keep himself apart from the others in order to maintain his authority.

So far, so sweaty, with the Scot tormenting the major at every opportunity, and a tense night-time poker game threatening to usher in the film’s first real burst of violence. But just at that moment, a bizarre event disrupts this uneasy community. An open-top Cadillac bolts through the station and hits a wall. Its occupants are a man and his blonde female companion (in fact his ex-wife), who is miraculously unscathed by the crash. As he makes a slow recovery from his injuries, she – in the form of Carroll Baker, star of Kazan’s Baby Doll (1956) – stalks around the station with a catlike grace, while the resident toms become highly agitated by her presence. It’s then simply a matter of who among them will make the first advances, and who she will pick for her pleasure. I won’t reveal more except to say it all ends unhappily… sort of.

Station Six Sahara was based on a stage play, and scripted by Bryan Forbes and Brian Clemens. Among the credits are two names familiar from Roman Polanski’s British productions, producer Gene Gutowski and editor Alastair McIntyre, and in many ways it’s akin to the Polish master’s early tales of perversion and imposition. But the significant figure is the film’s director, Seth Holt. Look up Holt in any film dictionary and you will find the same story: one of great promise unfulfilled, and of a significant loss to the burgeoning British film industry of the 1960s.

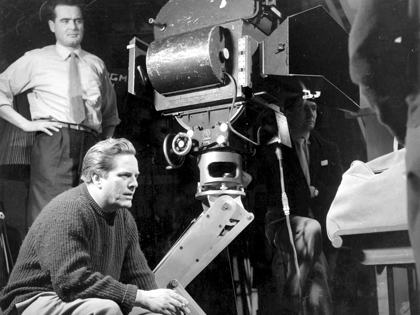

Seth Holt on the set of Nowhere to Go

Born in 1924, Holt began his adult life as an actor before being drawn into documentaries as an assistant editor. He was introduced to Ealing Studios by his brother-in-law Robert Hamer, graduating to editor on 1951’s The Lavender Hill Mob (among other titles) and producer on The Ladykillers (1955). He made the leap to director on one of Ealing’s last films, the prophetically titled Nowhere to Go (1958). Co-scripted by Kenneth Tynan, and featuring the film debut of Maggie Smith, it’s a cool, supremely visual thriller that in terms of its minimal dialogue and daring narrative playfulness is closer to the world of Jean-Pierre Melville than to any British precedents.

After serving a period as an editing doctor, in which capacity he was by some accounts responsible for saving Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) and The Entertainer (1960), Holt re-emerged as a director for Hammer with the excellent Les Diaboliques rip-off Taste of Fear (1961) and the creepy Bette Davis vehicle The Nanny (1965). But barren years were to follow, as Holt’s alcoholism resulted in his death in 1971 while shooting his final film: another Hammer production, Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb.

Was that sense of what might have been – and Movie magazine’s championing of Holt as one of the finest British talents around – justified? Certainly, most of his films were genre pieces, as opposed to self-generated works, and none could be regarded as a masterpiece. But as Station Six Sahara demonstrates, he had a remarkable gift for conjuring atmosphere, combined with an astute direction of actors (all are excellent) and a masterly use of montage. Sound alone is brilliantly used throughout, from the monotonous throb of the pumps to the whining crescendo of the Cadillac’s horn before the crash.

Contemporary reviewers acknowledged all of this: The Times commented that “for once in a British film some real erotic tension is palpable on the screen”, while Dilys Powell described the film as “true cinema”. However, all the critics were troubled by the total lack of explanation of the car’s sudden appearance in such a remote spot. Holt’s response: “I refuse to countenance any justification. It was a little coincidence. If people think of these things, then they don’t like the picture.”

As it happens, Holt’s favourite director was Buñuel, and personally I like to see this conceit as one of those surrealistic coups so beloved by the wily Spaniard. The coffin on the truck is another highly Buñuelian detail. Frustratingly, right now you’d be hard pressed to find a copy of Station Six Sahara to check whether or not you agree with me.

“Seth Holt… make[s] the most of a silly story, not by trying discreetly to muffle its clichés, but by playing up to them. No pretence of subtlety, no explanations… but at least this is filming with the courage of its own clichés.”

— MFB, October 1963

“With all due respect to the high-visibility charms of Carroll Baker, Station Six Sahara is better without her. The first half-hour or so has real possibilities as a cynical, corrosive close-up of desert boredom and unleashed, petty frictions. Enter Miss Baker in a random car crash, and… what started as murderous irony soon turns into a steamy farce that couldn't matter less.”

— Howard Thompson, The New York Times, November 1964

Vertigo inducing: Kim Newman on Terence Young’s debut Corridor of Mirrors (April 2011)

The Watcher in the Woods: Joseph Stannard remembers Disney’s cult 1980 fantasy (Lost and found, March 2011)

The Elia Kazan Collection reviewed by Graham Fuller (DVD, February 2011)

The Exterminating Angel and Simon of the Desert reviewed by Tim Lucas (DVD, April 2009)

The gun beneath the bubbles: John Exshaw on Eli Wallach (January 2006)

Moving at the speed of emotion: Martin Scorsese discusses Thorold Dickinson, one of his favourite British directors, with Philip Horne (November 2003)