Primary navigation

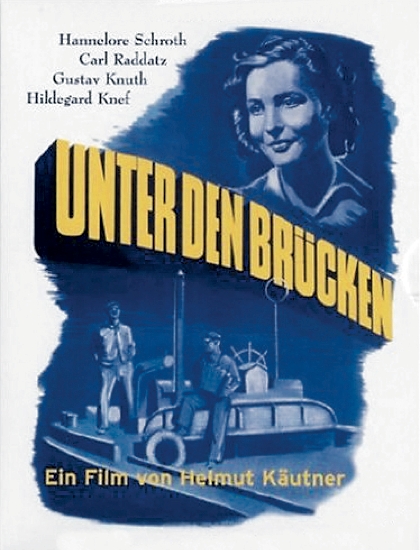

Though shot in Germany in 1944, Helmut Käutner’s Under the Bridges defiantly avoids any reference to Nazism. By Philip Kemp

from our June 2012 issue

It’s generally assumed that a filmmaker faced with a totalitarian regime like Nazi Germany has – if he plans to continue working – only two options: self-exile (Fritz Lang) or collaboration, however reluctant (G.W. Pabst). But there is a third option, one that might be called internal exile: to stay and carry on making films while avoiding any reference to the regime or its ideology – to act, in fact, as though it didn’t exist. Not an easy route, and one that requires some very fancy footwork. But it’s the one that was chosen – and followed with some success – by the director Helmut Käutner.

Born in Düsseldorf in 1908, Käutner started out in the theatre – first as an actor and then, with three friends, as a member of a cabaret group who called themselves Die Vier Nachrichter (The Four Reporters). Formed in 1930 in Munich, the group toured all over Germany; it was banned in 1935, not apparently on account of any satirical barbs, but because one of its members was Jewish and another had a Jewish wife. Käutner, who always described himself as apolitical (“Politics in every form I have encountered... has always inspired in me no other feeling than boredom, annoyance or nausea”), turned to writing screenplays, and in 1939 got the chance to direct one of them himself.

A fluffy romantic comedy set during a diplomatic conference in Lugano, Kitty and the World Conference (Kitty und die Weltkonferenz) was banned in Germany thanks to its favourable portrayal of the urbane British foreign minister – but it was shown in German-occupied Prague. Undeterred, Käutner went on to make eight more features under the Reich. Some of them ran into trouble. Romance in a Minor Key (Romanze in Moll, 1943), adapted from a story by Maupassant, offered a study of a doomed adulterous love-affair. Described by Georges Sadoul as “the only film of real quality... produced in Germany during the war”, its romantic melancholia owed a good deal to Ophuls and Carné, and nothing to the prevailing ideology. Goebbels denounced it as “defeatist”.

Port of Freedom (Die Grosse Freiheit Nr 7, 1944), Käutner’s first film in colour, was an official commission, intended to portray “the art of the German song”. What he came up with was a raunchy tale of nautical life in Hamburg, set largely around the city’s Reeperbahn red-light district. Admiral Doenitz got Goebbels to ban the film, furious that German sailors should be shown drunken and whoring – and that Käutner had avoided showing swastika-flagged warships by blanketing his harbour scenes in fog.

In the final months of the war Käutner made what’s often considered his finest film, Under the Bridges (Unter den Brücken, 1945). The presiding spirit this time was Jean Vigo, and echoes of L’Atalante abound: once again we’re on a barge with two men on board, their comfortable, borderline-homoerotic relationship disrupted by the arrival of a woman. Hendrik (Carl Raddatz) and Willi (Gustav Knuth) are the crew and co-owners of the barge Liselotte, being towed up the Havel towards Berlin. They enjoy fleeting liaisons with various women (we see Carl taking leave of one of them, played by Hildegard Knef in an early role), and debate buying a motor for the barge to free them from the dictates of the tow line. Apart from anything else, this would allow them to stop and chat up the girls who watch them from the bridges they pass under.

Moored near Potsdam one night, they see a woman on a bridge, apparently about to jump. When they accost her, Anna (Hannelore Schroth) denies any suicidal intent, but agrees to spend the night on their barge, since the last bus to Berlin has gone. Next day they offer her a lift to the city. Inevitably, both men fall in love with her; their rivalry threatens to break up their partnership.

It’s a simple, even archetypal story, and Käutner films it with a limpid charm that makes the most of his quiet waterscapes and skies. The title song, jaunty but with a touch of wistfulness, recalls the wartime hit ‘Lili Marleen’ (whose music was composed by Norbert Schultze, one of Käutner’s partners in Die Vier Nachrichter). Neither the humour nor the pathos is overdone, and the details of the bargees’ domestic life are filled in with affectionate care. True, Under the Bridges is no imaginative masterpiece on a par with L’Atalante, but it isn’t diminished by the comparison.

What’s most remarkable about the film, though, isn’t so much what’s in it as what isn’t. It was shot during the final year of the war in Europe, between May and October 1944, largely on the locations that it depicts, from Havelberg on the North Sea coast up the river and into Berlin itself. The Red Army was advancing through East Prussia, the Allied forces were approaching the Ruhr, and Germany was under almost nightly bombing raids. “Often we had to look for a new location because the old one had been bombed,” Käutner recalled. “We spent most of the nights clutching our precious equipment under bridges, not knowing that they had long since been mined.”

Yet there’s not a mention of the war in the film – not even indirectly. We see no swastikas, no bombed buildings, nobody in uniform. No one makes patriotic speeches or gives Hitler salutes. Berliners are shown sunbathing, or in rowing-boats on lakes. The film implicitly stakes a claim (as Erwin Leiser wrote about Käutner’s wartime films as a whole) “for the right to a free life as opposed to the requirements of discipline”.

Only once during the war years did Käutner succumb to official pressure. Till We Meet Again, Franziksa! (Auf Wiedersehen, Franziska!, 1941) is about a German war reporter travelling the globe for a news company. Finally he receives his call-up papers. The Propaganda Ministry insisted on a scene being included in which his wife urges him to go and fight for the Fatherland. Käutner shot the scene – but enclosed it within a pair of fades, like inverted commas, so that it could be removed without any damage to continuity or dramatic logic.

After the war Käutner, cleared of any taint of Nazism, continued making films for another 20 years before moving into theatre and television. He was one of the few worthwhile German directors in the decades prior to the New German Cinema. But he never quite regained the creative heights of Romance in a Minor Key or Under the Bridges – the films he made in internal exile.

“Under the Bridges is actually my favourite film. Anyone who sees it today would not be able to understand that at the time, when there was no future any more and Germany’s final collapse was a question of days, it was possible to film such a simple, almost idyllic story… When I really think about it, what we did arose from the filmmakers’ stubbornness to allow any of the horror which surrounded us to seep into our work.”

— Helmut Käutner, quoted in German Cinema: Texts in Context, edited by Marc Silberman (Wayne State University Press, 1995).

Group Portrait with Lady remembered by Vlastimir Sudar (May 2012)

Artist of the floating world: Graham Fuller advocates L’Atalante as one of the Greatest Films of All Time (February 2012)