Primary navigation

Viewing Occupied Paris through a Muslim prism, Ismaël Ferroukhi’s muted drama is a more contemplative sort of Resistance film, says Catherine Wheatley

From our June 2012 issue

“Freely inspired by actual events,” as its opening title announces, Free Men intermingles fact and fiction to tell the story of a Paris mosque that supplied North African Jews with forged Muslim identification, even as the Gestapo bore down on the place of worship.

Free Men reimagines history through the eyes of Algerian immigrant Younes (Tahar Rahim), who at the beginning of the film is making a living through a black-market trade in cigarettes and stockings. After being hauled in by the Vichy police for his illicit activities, Younes buys back his freedom by agreeing to spy on the local mosque and its resident rector, Si Kaddour Ben Ghabrit (Michel Lonsdale, in a neat reversal of his role as a French monk in 2010’s Of Gods and Men). It isn’t long before he finds his allegiances shifting under the influence of velvet-voiced singer Salim (Mahmoud Shalaby) and Leila, a beautiful Resistance fighter (an underused Lubna Azabal, last seen in Incendies).

At first glance, Free Men’s exposé of yet another little-known aspect of the Occupation might seem hopelessly familiar. The subject-matter and loosely generic format – blending thriller with film noir – call to mind Rachid Bouchareb’s Days of Glory (2006) and Outside the Law (2010), as well as such Resistance classics as Jean-Pierre Melville’s Army of Shadows (1969). Yet Free Men fails to match the tension of these antecedents, confining the action to one brief car chase/shootout.

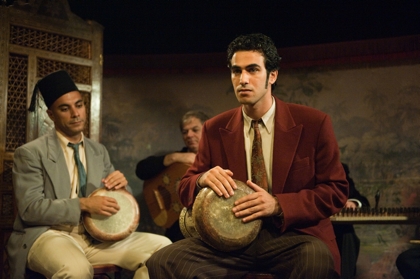

Nonetheless, director Ismaël Ferroukhi has some subtle twists up his sleeve, albeit ones that temper rather than heighten the film’s emotional pull; not least of these is the central place of music. While we follow the action almost exclusively from Younes’s point of view, the character himself is largely silent (Rahim, costume notwithstanding, seems to have strutted into 1940s Paris straight off the set of A Prophet, bringing to Younes the same combination of taciturn charisma and bewildered vulnerability that bore up Jacques Audiard’s 2009 prison drama). Time and again Younes meets the questions put to him with no more than a searching gaze. By contrast, the strains of strings, woodwind and drums seem to capture a powerful universal sentiment that exists beyond words.

The film’s standout sequence sees Younes listening to Salim’s band for the first time and transforming from motionless outsider to a bobbing, swaying participant in a communal movement. If it’s impossible to say at this point what Younes might be thinking, it’s worth noting that the instrument Salim is playing is the same darbuka that Younes traded for a packet of cigarettes in the film’s opening sequence: the move from object of commerce to symbol of comradeship is suggestive of an ideological shift.

Finishing on a solemn note of irresolution (which foreshadows, perhaps, the future fate of Younes and his fellow Algerians), Free Men fails then as a genre piece. But it succeeds as something more contemplative, raising questions about the relationship between race, nation, creed, religion and even sexuality without ever sliding into didacticism. It’s a thoughtful and thought-provoking piece of filmmaking, which repays repeat viewing.

Memento mori: Jonathan Romney on Of Gods and Men (January 2011)

Unknown soldiers: Ali Jafaar on Days of Glory (April 2007)

Sex, lies and videotape: Catherine Wheatley on Hidden (February 2006)

L’Arche du désert reviewed by John Mount (August 1999)