Primary navigation

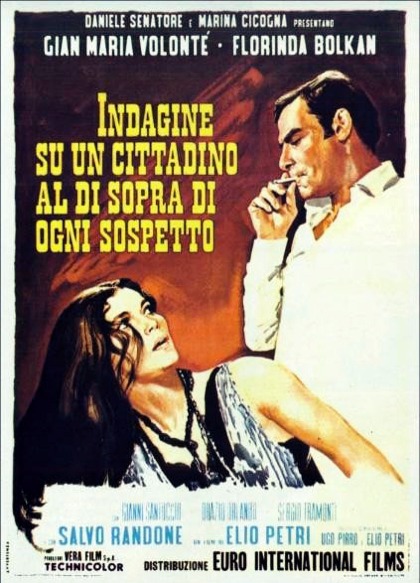

Mike Hodges investigates a dark tale of murder, corruption, kinky sex and game-playing in Elio Petri’s 1970 box of tricks

“How are you going to kill me this time?”

“Today I’m going to cut your throat.”

And he does just that. But not before he’s removed his immaculately tailored cream suit, carefully hanging the jacket on an antique clothes horse before ensuring the sharp creases in his trousers are preserved. Uniforms, including business suits, are important in Italy. Carabinieri, cardinals, Mafioso, priests, Il Papa, Mussolini, black shirts – the list of sartorial examples is endless. But the trouble with uniforms is that once they’re taken off, as they inevitably are, their power immediately evaporates and the naked occupant is left looking as vulnerable as a newborn baby. And so it is with the assassin before he slips under the black sheet with the woman; pulling it over them both like it’s a shroud. After some manoeuvring she suddenly rises up, groans as if sexually climaxing and slumps on top of him. Only when he slides from under her torso do we see any blood. Using the sheet to wipe it from his chest and neck, around which a gold cross and chain glint with each movement, he seems about to gag.

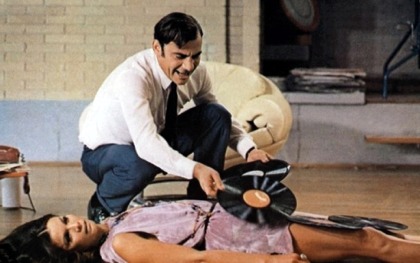

We are just four minutes into Elio Petri’s Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, and throughout this scene of cold-blooded murder we’ve been treated to a wonderfully jaunty score by Ennio Morricone. He seems to know something we don’t. We do know that the couple have been playing kinky sex games for some time, but now wonder if, with her throat cut, the game-playing is over. Or is it just beginning? Morricone lets us know it’s the latter as the film takes an even stranger turn. The killer starts both to eradicate evidence of his presence in the room and create it simultaneously. “Precision, precision,” he says later in the film.

Watching actors well versed in film craft working their movements and their use of props into an elegant and economical shape gives enormous pleasure. And Gian Maria Volonté is just brilliant when laying the trap in which he should rightly be caught. He leaves a strand of his sky-blue tie snagged in the victim’s fingernail; he steps in her blood and leaves a trail of footsteps; he empties her jewellery box but leaves wads of money in full view for the cops to see. Finally he takes two bottles of champagne and leaves. He arrives with them in his car at Rome’s police headquarters. The killer is also the homicide chief. What’s more, he’s just been promoted to lead the influential political squad. Hence the champagne. Morricone keeps underscoring the fact that the game is still in play – but now it’s a different game.

Petri’s film was made in 1970. It won the best foreign-language film award at the following year’s Oscars, but has slipped from view since. Unfortunately I can’t remember exactly when or where I saw it. All I remember is the indelible impression that one viewing made on me. Only when I finally traced and viewed it last week did it unlock a cascade of memories that may be pertinent to the different game Petri is examining after the murder.

Around the early 1970s, and for a decade or more afterwards, I had strong work connections with Italians, including Fellini in 1983. It started in 1971 when I was writing Pulp, my second feature film, which was to be shot in Italy. We abandoned the idea – much to the dismay of our Italian production manager – because the use of each location necessitated negotiating with the Mafia. Gitt Magrini, the film’s costume designer (The Red Desert, 1964; The Wild Child, 1969; The Conformist, 1970) and I became great friends. Passing through Rome some years later she invited me to a party. It turned out to be at the most elegant luxury residence I’d ever experienced. Celebrities wall to wall. There had recently been local elections resulting in a big swing to the Communist Party. Being at a loss for conversational topics I took it upon myself to ask everybody I met how they had voted. All had voted communist. When pursued as to why, being so rich, they had voted so far to the left, they replied in astonishment: “In Italy communism is very different.” But then everything is different in Italy. It really isn’t surprising they invented opera.

In 1980 I was asked by Dino De Laurentiis, the Italian film mogul, to direct Flash Gordon; an unlikely choice. Once, during the madness of shooting, I asked him why he’d chosen me, expecting him to express some recognition of my talent. Instead he replied: “Because I liked your face.” And he meant it. I was directing a multi-million-dollar film because he liked my face. But then Dino actually believed Flash would save the world and couldn’t understand why the crew laughed uproariously at the daily rushes. I had to ask them to stop. And then there was the wondrous production designer Dino had brought on board. Although I adored Danilo Donati (Fellini’s Satyricon, 1969; and Casanova, 1976), I swear he never read the script throughout the production, and he certainly built the huge sets purely for his own self-gratification. In one, Arboria, the trees were so huge I literally couldn’t get the camera in. When I demurred, Dino asked: “Michael, how many movies you make?” “Three.” “I make three hundred.” And with that he smacked his hands like a pasta maker.

While Petri’s film is undoubtedly about the corrosive power of power, a well-trodden path, maybe it’s also about another game? Late in the film we discover that at their previous tryst Augusta Terzi (the exotic Florinda Bolkan) had called her lover “a baby”. Worse, she had gone further, taunting him that he also made love like a baby. That jibe cost Augusta her life. Yet every action we witness of the police inspector supports her assertion; metaphorically he’s never left his mother’s tit and when he he balls and screams, terrorises and bullies. What’s more, all the men surrounding him seem to be in the same retarded state. So maybe Petri is also saying that life itself is just a childish game, a one-off performance in which nobody grows up. Possibly. After all, Petri, with his wonderful sense of irony, must recognise that filmmaking itself is a childish occupation; all make-believe and let’s pretend.

Mike Hodges is best known as a filmmaker but has also written and directed for theatre and radio. He’s also directed opera and recently completed a satirical novel, Watching the Wheels Come Off, which is available on Amazon

“It is easy to understand why this film caused such a furore in Italy, for its loathsome central character expresses aspects of Fascist ideology which look back to Mussolini as well as having relevance for our own time. Petri obviously wanted to make a polemical film, but the sheer weight and relentlessness of his attack often mitigates against him. Although Gian Maria Volonté plays with his usual depth and intelligence, Petri often pushes him into ranting caricature, employing an excessive number of close-ups which tend to inflate the character rather than bring him into sharper focus.”

— John Gillett, Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1971

Maestros and mobsters: Nick Hasted on a new generation of Italian filmmakers emerging from the shadows of political corruption and cinematic nostalgia (May 2010)

Prince of darkness: Paolo Sorrentino talks to Guido Bonsaver about his portrait of former Italian leader Giulio Andreotti, Il Divo (April 2009)

The killer inside: David Thomson on Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (March 2008)

Geometry of feelings: Guido Bonsaver on the high-modernist cinema of Michelangelo Antonioni (July 2005)

A clown with wrinkles: Guido Bonsaver admires Fellini’s less-loved later works (August 2004)

I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead reviewed by Ryan Gilbey (May 2004)