Editorial

UKFC R.I.P.

27 July 2010

Nick James reacts to news of the abolition of the UK Film Council. Below, we run his editorial from the September issue of Sight & Sound, warning against taking the the axe to our already struggling art-film sector

I am writing this note from the Sarajevo Film Festival where the handful of Brits here have reacted with incredulity at the news that the DCMS is to abolish the UK Film Council.

I am writing this note from the Sarajevo Film Festival where the handful of Brits here have reacted with incredulity at the news that the DCMS is to abolish the UK Film Council.

The September issue of Sight & Sound, due in the shops next week, contains an editorial on the subject of government cuts which is now, in the light of this news, out of date, so we have decided to publish it online with this introduction.

As you will read, my main concern was that cuts in government support would endanger the continued existence of film as an art form in the UK. While the UKFC in its original form did little for that cause, in more recent times it has realised the cultural value of such a cinema. Until we know what kind of funding arrangement will replace it, we can only hope that cultural value will be the priority.

A full history of the UKFC will appear in Sight & Sound’s October cover date.

Rough cuts

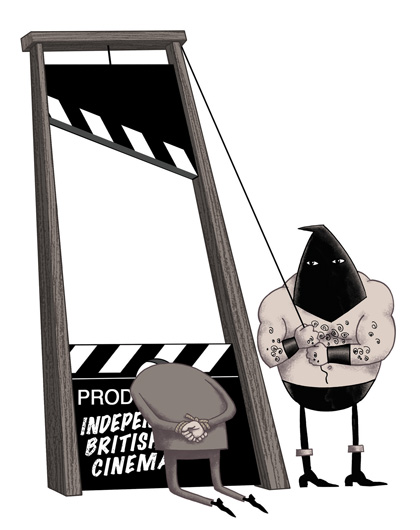

Illustration by Simon Cooper for Sight & Sound

Recently I contributed to an item on BBC2’s The Review Show about whether or not the arts flourish during times of economic recession. As is the way with TV, what I said was edited down from an equivocal position to a definite statement, but I’m not complaining. Right now, the less said incautiously about arts funding, the better. Since the UK government’s cabinet ministers are competing to demonstrate how deeply they can cut budgets to meet the nation’s substantial deficit, the arts – though their drain on the public purse is just 0.07 per cent – have become the softest of soft targets.

As if to demonstrate that we’re in for dire punishment, culture secretary Jeremy Hunt is cutting his own DCMS staff by up to 50 per cent. Meanwhile the BBC is gearing up for its inevitable war over its licence fee. Having already seen the £45 million promised towards a National Film Centre withdrawn, the BFI (which owns this magazine) is preparing its own response to the cut in its grant-in-aid likely later this year. Since no one yet knows the details, and the government has promised a review of its involvement in the film sector, it’s difficult to speculate as to the damage extensive cuts will inflict.

But damage will be done, and what’s most at risk is the continued existence of film in the UK, not as an entertainment medium but as a practised artform. Specifically, the prospects for British film-makers with ambitions to create truly great cinema seem very bleak indeed.

Before I get to that, however, let’s backtrack to the matter of how the arts respond to hard times. It’s no accident that renaissance painting, German classical music and the English novel all coincided with periods of economic expansion. Cinema also tends to thrive culturally as well as commercially when times are good, but the strange anomaly is that, separately, cinema box office seems impervious to economic conditions – much of Hollywood’s Golden Age, for instance, coincided with the Great Depression. That recent recessions also have not affected box-office trends is demonstrated in the latest edition of the UK Film Council’s Statistical Yearbook. What cinema provides during such tough times is escapism, the chance to forget our troubles (such as the fact that, compared to cuts in social services, what happens to cinema must perforce seem trivial).

Government ministers of all stripes tend to think that escapism is what the cinema is for. As long as big studio films continue to be made at UK facilities and the cinemas themselves are full, what can possibly be wrong? But one long-term problem will have an impact over time on Britain’s position in international cinema: how can young British film-makers get to be good at what they do? One of the reasons why Ingmar Bergman, for instance, made half a dozen classics of art cinema is that he made more than 60 films. As Nick Roddick shows in our September issue, no one today gets such a chance, which is perhaps why so many British directorial debuts offer nothing more than neat, anodyne, self-censored packages of cute entertainment. Many low-budget British films I saw at Edinburgh this year, for instance, strove mainly to show off the talents of those involved. The films as works were secondary to this shop-window attitude.

And what the statistical yearbook tells us is that the independent film sector in the UK – the proving ground for all young film-makers – is under increasing pressure. Where there were 74 independent features made in 2003, in 2009 there were just 40. You might say that’s natural during a recession, but then the industry is wrongly seen as recession-proof – and the R&D side of it is most emphatically not. Given the apparent success of our industrial activity, it is remarkable how very few new directorial talents have been nurtured here in the past decade. Where are the new Shane Meadowses and Lynne Ramsays, let alone the new Ridley Scotts? The answer is, of course, that they’re out there, but they haven’t had the chances to develop that their forebears enjoyed.

The hope expressed by some is that hard times will fuel a reactive cultural renaissance. After all, austerity inspired a tremendous outpouring of political drama in the 1980s in response to Thatcherism. But the institutions that supported that work – primarily the BBC and Channel 4 – take fewer cultural risks than they used to, and it will take time for an appetite for such work to show itself, just as it will take time for film-makers to pick up the threads of a mothballed radical tradition.

The art film in Britain already subsists on slender means. Given that the coming cuts are liable to affect each and every one of its support structures – the television channels, the film cultural bodies – we can only assume that the consequences will at best be felt for decades, and at worst prove fatal. The amount the UK government invests in film as an artform is truly tiny. The future rewards for continued support, both culturally and financially, are great. But in the season of the cleaver, who will dare to stay their arm?

See also

In bed with the Film Council: Nick James on the new screen agency’s clean-slate intentions (January 2001)

Digital deluge: what are the consequences for British cultural films if DV is the only option, asks Nick James? (October 2001)

Eat my shorts: James Bell looks at the consequences of DV on short film-makers (May 2004)

Beyond the horizon: Mark Cousins on Peter Sellers’ New Crowned Hope commissions (rejected by the UK Film Council, Channel 4 and the BBC) (July 2007)

Sight & Sound coverage of Film Council productions:

Nowhere Boy reviewed by Trevor Johnston (January 2010)

Romantic setting: Jane Campion talks to Nick James about Bright Star (December 2009)

Better Things reviewed by Jonathan Romney (February 2009)

Man on Wire reviewed by Catherine Wheatley (August 2008)

A royal rumpus: Nick James sees Steve McQueen’s Hunger at the Cannes Film Festival (July 2008)

London to Brighton reviewed by Michael Brooke (December 2006)

Red Road previewed by Hannah McGill (November 2006)

The Wind That Shakes the Barley reviewed by Edward Lawrenson (July 2006)

Ballad of the wild boys: The Proposition’s John Hillcoat and Nick Cave talk to Nick Roddick (March 2006)

Vera Drake reviewed by Ryan Gilbey (January 2005)

The Girl with a Pearl Earring reviewed by David Jays (February 2004)

Touching the Void reviewed by Richard Falcon (January 2004)

Young Adam reviewed by Philip Kemp (October 2003)