Primary navigation

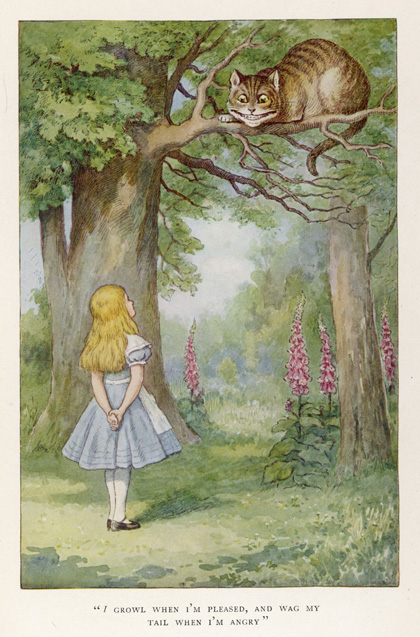

John Tenniel’s Alice. Courtesy Mary Evans Picture Library

Lewis Carroll’s heroine Alice and the Wonderland she visits have meant very different things to different artists. Mark Sinker surveys the key films –and illustrations – that brought her to life

“Well,” thought Alice to herself, “after such a fall as this, I shall think nothing of tumbling down stairs! How brave they’ll think me at home! Why, I wouldn’t say anything about it, even if I fell off the top of the house!” (Which was very likely true.)

— Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

In Terry Gilliam’s Tideland (2005), as Jeliza-Rose sits with her junkie dad on a night bus, fleeing the scene of her mother’s OD, she is reading by torchlight from her favourite book, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, when her dad says, “We’re not gonna be safe till we get to grandma’s house.” He is, of course, wrong about grandma’s house. In her unflappable, serious-minded, 11-year-old way, Jeliza-Rose will have to cope with more drugs, more death and the odd sex drives of some perilously feckless adults when she gets there.

She’s reading the opening chapter, ‘Down the Rabbit-Hole’. As she holds the book in her lap we see an old-style black-and-white picture: Alice falling past a cupboard, grabbing at a jar as she passes. “D’you think mom will keep falling, till she falls right through the earth?” Jeliza-Rose asks. But her dad is lost in his own upside-down world. She falls asleep, and the bus passes under a bridge into the bright new dream-space of the prairies.

The illustration is at once recognisable and strange. John Tenniel, a respected Victorian political cartoonist for Punch magazine, is by far the best-known Alice illustrator. He was brought in by Lewis Carroll when friends persuaded the author that his privately printed Alice’s Adventures under Ground (1864) was strong enough to publish, but perhaps without his own evocative but artless pictures. And it is recognisably Tenniel’s Alice that we glimpse in Tideland: her hair long, blonde and off her forehead; her clothes a frock and pinafore; white stockings and strapped Mary Janes on tiny feet; her age surely more than the seven years Wonderland'’s text demands. And, of course, there’s her frown – because while Carroll often has Alice laughing, Tenniel never does.

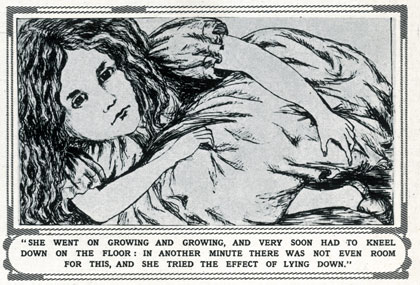

Lewis Carroll’s Alice. Courtesy Mary Evans Picture Library

Tenniel executed around 100 woodcuts for the various Victorian editions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its 1872 sequel Through the Looking Glass (including a handful of later colour plates, which is how we know her frock is light blue). Nearly a century and a half later, his is the instantly recognisable Alice we see in adverts, parodies and jokes: an icon fashioned for a lasting place in our shared cultural heritage. But the image seen in Tideland confirms the strength of Tenniel’s gravitational pull, in a curious way: because, utterly familiar as it seems, the image is not by Tenniel (or if it is, it’s not canonic). After Wonderland's court-scene frontispiece, Tenniel’s first narrative image is of the White Rabbit; in his second, Alice unveils the tiny door. Almost certainly, Tideland's falling Alice is a pastiche by a successor, careful to stay within the distinctive conception and brand.

This precise conception of Alice abides despite the fact that, since the close of the 19th century, more than 50 other artists have illustrated these stories, including Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst and Peter Blake, as well as such front-rank children’s illustrators as Arthur Rackham, Mervyn Peake and Tove Jansson – not to mention the modern-day political cartoonist Ralph Steadman. Furthermore, at least 20 film and television versions, including silents, animation and porn, have been made, with Tim Burton’s the latest to reach our screens.

Lewis Carroll – more properly Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, lecturer in mathematics and logic at Oxford, Anglican deacon but never priest, amateur photographer and conjuror – died in 1898. In the new century, Alice art emerged that tried – and largely failed – to break with the Tenniel template; the new medium of cinema, however, reaffirmed this template. Three known silent Alice films were made, in 1903, 1910 and 1915. (The damaged fragment that survives of Cecil Hepworth’s 1903 version has recently been restored by the BFI.)

The cinema was adept at phantasmagoria from the first – Georges Méliès made a dozen films in 1903 alone, featuring such Alice business as size-change and vanishings. But, perhaps awed by the book’s status as a ‘children’s classic’, the early Alice films approach their special effects shyly and stagily, with a literalist clumsiness that sits quite timidly in Tenniel’s shadow. Yet there is charm too: the poetry of abandoned technologies, as teasingly evocative of lost ideals as it is inadvertently sceptical of current identical illusions. Such poetic charm is what drew the surrealists to silent film when it ceased to be the industry norm – and, indeed, to the Victorian journalistic woodcut, and to Carroll himself. Louis Aragon and André Breton lauded Carroll, for whom nonsense, as Breton wrote in his 1939 Anthology of Black Humour, constituted “the vital solution to a profound contradiction between the acceptance of faith and the exercise of reason, on the one hand, and on the other between a keen poetic awareness and rigorous professional duties… No one can deny that in Alice’s eyes a world of oversight, inconsistency and, in a word, impropriety hovers vertiginously round the centre of truth.”

In old age, Max Ernst created a sequence of Alice-themed lithographs – half spindly scribble, half geometric diagram – for Lewis Carroll’s Wunderhorn, a 1970 German edition of texts by Dodgson, including excerpts from his 1887 textbook The Game of Logic. Ernst’s earlier Une Semaine de bonté, a 1934 “novel in collage” consisting of 184 images featuring animal-people in curious encounters and spaces, was fashioned from anonymous journeyman woodcuts of similar style, feel and date to Tenniel’s illustrations. The stolidity characteristic of such figures and settings is revealed to have sedimented within them all manner of unobserved vivid energies, unleashed by the passing of time, the turn of fashion and sly surrealist juxtaposition.

Norman Z. McLeod’s 1933 Alice in Wonderland

A year before Ernst’s collage-novel, Paramount released its all-star Alice in Wonderland, with a cast including Gary Cooper, Cary Grant, Edward Everett Horton and W. C. Fields – as the White Knight, the Mock Turtle, the Mad Hatter and Humpty-Dumpty respectively – and 19-year-old Charlotte Henry as Alice. This too was a collage, with characters from both books, and the grisly tale of ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ – and the little oysters they prey on – rendered as a cartoon sequence by the Fleischer Brothers.

As fidelity is set aside, Hollywood – by accident or design – begins to unveil what lies behind the apparent innocence of this children’s classic. Where the 1903 silent Alice features a Cheshire Cat that’s merely a plump, cross, ordinary Persian sat doing militant nothing as the grown-up playing Alice (dressed Tenniel-mode) overacts, Paramount’s Cheshire Cat, if anything, heightens the bizarre monstrosity of Tenniel’s original, its grin hideously distending its face. As this Cat vanishes, its outline becomes a bright, ghostly light in the sky, marking less a wayside character with odd properties and a snide attitude than some amusing yet sinister all-surveying deity – a deity who will eventually encourage Alice to challenge and overturn Wonderland’s ruling dynasty.

And yet this classic book is routinely treated as a quaint, almost chintzy relic of cosiness – a story that is, when you think of it, that of a very small girl alone in a world of extreme flux and chaos. In Wonderland, size, time and status are all nagging open questions. Behind the Looking Glass, Alice, the girl-pawn armed with nothing but what she can recall of her common sense, is left unprotected on a massive darkling battlefield. Social hierarchies, in the pomp of their self-confidence, are laughed away; small and large are concepts as fluid as the roles of monarch and infant. Death jokes and poems abound – the chirpy little oysters are not the only ones that end up eaten.

Suspended animation

Walt Disney’s 1951 Alice in Wonderland

Subsequent film versions have revealed other dimensions to Carroll’s tale. In the book, it’s the arrival of the White Rabbit that signals to sleepy Alice – bored as she is by dull prose in a summery meadow – that something is up. What Disney’s animated Alice in Wonderland (1951) straightaway adds is that Tenniel no longer holds sway. In place of the illustrator’s austere Rabbit (and indeed Carroll’s flustered and fussily bullying one) is a dumpy, goofy, bouncy, cutesy ninny – part Thumper-ish energy, part Geppetto-ish querulousness, and clearly modelled, voice-wise, on Tex Avery’s (and MGM’s) cartoon character Droopy.

Being a Disney film, this Alice doesn’t entirely dodge saccharine moralism. Dreaming of a world that’s all nonsense all the time, Alice is given what she wants, and thus learns to appreciate – in the exhausting pell-mell of a universe in thrall to meaninglessness – the order of governess-ruled reality. But the film’s paws are planted in the playful rigour of Disney’s own ‘Silly Symphonies’ and Warners’ ‘Merrie Melodies’, the anarchic semi-abstract shorts that made up toon-world in the 1930s and 40s. The quasi-highbrow Disney feature Fantasia (1940) was similarly episodic: as a madcap recap of this hit, Alice is also the closest Disney ever came to the frenetic screwball aesthetic of rival toon-makers MGM and Warners, and such directors as Avery and Chuck Jones.

Though it opens in an exaggeratedly tranquil Hollywood Oxford, the paint-by-numbers realism speedily explodes into knockabout impossibility. The strongest characters have control, Chuck Jones-style, over their own mise en scène (the Caterpillar, for instance, is an orientalist sultan whose hookah realises words as interrogatory letters, text-speak style: “Who RU?” “Y?”) or even over their own bodily integrity (the Cat lithely links and unlinks his own purple stripe-hoops and is, of everyone Alice encounters, the most at home in the visual and verbal anarchy). After the slow glide down past the fairground-mirror distorted shelves of the rabbit hole, and the first spasm of size-play, the ‘Pool of Tears’/‘Caucus-Race’ scene combines with the ‘Lobster Quadrille’ in a choreography of sea beasts and nautical memes. Just before the final chase scene, a kaleidoscopic Busby Berkeley troupe of playing cards swirls, fans and shuffles into modernist anti-figurative patterns within the palace garden maze. At the end, as Alice flees the Wonderland hordes, they seem to be coming for her out of the same vortex that constitutes the ‘Looney Tunes’ iris-out tunnel. Except this time there’s no baby-faced Porky Pig to declare “Th-th-that’s all folks!”

Jonathan Miller’s 1966 Alice in Wonderland

A cartoon, of course, can achieve a profusion of irreality beyond the black-and-white means of British television in the mid-1960s. Jonathan Miller’s response, in his 1966 BBC version, is to make an inspired virtue of such limitations. Over the drifting fly-buzz of Ravi Shankar’s sitar, which suffuses a very English landscape with the flavour of the lost Raj, Miller takes the eventless dullness of Alice’s waking world and imports it into her dream, amplifying everything strange about the mundane real. Except for the Cat (very vocal, rarely visible), the animal characters in this version are played as and by humans, a cross-section of British serio-comic character acting at its mid-60s zenith: a rabbity Wilfrid Brambell, a mousy Alan Bennett, Michael Redgrave as the Caterpillar, Peter Cook as the Hatter. Size-shifts are simple jump cuts; the pool of tears is a slow-motion cutaway in variant granularity. The irreal is unimportant to Miller, whose interest is social psychology.

Alice is a 14-year-old non-actress, Anne-Marie Mallick, in her only screen role, and she emanates an imperious, baffled, resentful boredom at the stupidity of the grown-up world she’s enduring: Wonderland here is less an escape from lingering Empire memories than a distillation of them. Not the military or economic engine room of colonialism, but its backstage spaces: its corridors, kitchens, libraries, potting sheds, its tea parties and croquet meets. Food is piled high; time stands still. Here are large, elegant gardens that can hardly cultivate themselves, spacious houses full of decorative bric-a-brac, Victoriana as the already dusty museum of itself – a realm of effortless material accumulation, the means of its acquisition and maintenance rendered as invisible as the Cat.

The portal this time is not visual but aural: Shankar’s sitar, Cook’s strangled, self-abnegating obsessive-compulsive terror as the Hatter, and above all – in the most heartbreaking sequence in Miller’s film – John Gielgud as the Mock Turtle. In languid melancholy and unworded lament, Gielgud’s Turtle speaks and sings to that dimension of Empire which is not unalloyed robbery with menaces, but at the same time a vast project of busy practical idealism, a rebuilding of all the fallen world in the muscular, problem-solving self-image of the British of a certain era – their confidence, their anxiety, their awareness and denial of failure and contradiction.

This mock beast named for a fake food – paired with a Gryphon played by that puckish moral humbug, Malcolm Muggeridge – invokes his beloved teacher, a turtle they called Tortoise, and all that institutional web of high-ranking schools and great teachers that held together the grand global scatter of red-stained conquests. And then these two already elderly-seeming British gentleman, Gielgud and Muggeridge, dance, stepping out a child’s idea of a formal dance – the ‘Lobster Quadrille’ – while silhouetted on the beach against the whitening sky, the haughty girl walking in their midst. “Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, will you join the dance?” An invitation to established society’s ball, accepted or declined – and it’s impossible to know which the more desolate choice will be.

Oxford days

Gavin Millar’s 1985 Dreamchild

The Alice tales began at a boating picnic on 4 July 1862, as improvised by Dodgson to entertain the three daughters of his colleague Henry Liddell, dean of Christ Church. Dreamchild (1985) is set both in that Oxford summer and in New York, 1932, where Alice Hargreaves (née Liddell), now an ailing widow of 80, is accepting an honorary degree from Columbia University on Dodgson’s behalf, to mark the centenary of his birth. Scripted by Dennis Potter and directed by Gavin Millar, this sweetly made film is a fictionalised elaboration of a historical event. Made in a decade when adult predation on the young was exploding as a topic of public fright, it’s an anti-romantic romance that challenges cynical expectation, burrowing down into the sugar of emotional truth that wised-up modern truism can miss.

Mrs Hargreaves’ teenage maid Lucy falls for Jack Dolan, a semi-scrupulous New York journalist who romances her to get access to this elderly muse of Carroll’s legendary books. A “most fraudulent young man”, the amused widow calls the plausible Dolan, and there’s a very Potterish pleasure in discerning, behind frailty and bewilderment, the common-sense spark of the girl who beguiled Dodgson 70 years before. “It’s not cheap music that’s disturbing you, it’s your youth,” she tells her maid. (The power of cheap crooner tea-jazz is Potter’s signature, of course.)

Against the disenchanted present-day conception of Lewis Carroll – as shy, virgin bachelor with a creepy thing for small girls – Potter sets the proposal that adults, however hag-ridden, can be both wiser and nicer than children; he also reveals a scepticism towards sex as the trumping value, and a renewed quasi-Victorian trust in the generous kindness of agenda-less friendship. We’re suspicious of this last because, as self-proclaimed masters of all fleshly wisdom, it is something we envy enormously.

As the ceremony nears, Mrs Hargreaves is troubled by phantasms from her past: her family broke off relations with Dodgson, but she can’t recall why. Is there something terrible that she knows but cannot face? In the form of Jim Henson’s puppets, Carroll’s characters – Caterpillar, Gryphon, Mock Turtle, the Mad Tea Party threesome – rise into her waking dreams not as cheeky little Muppets but as demons, hairy, hulking, ugly and threatening. At the tea party in particular, Hare and Hatter – feral and corpse-like – torture the Dormouse with boiling tea and bully Alice about who she is and should be. This nightmare colours the remembrance of another picnic long ago: the follow-up boat trip when young Alice transferred her affections from Dodgson (Ian Holm) on to her future husband, Hargreaves. As Dodgson reads ‘The Lobster Quadrille’, Alice, embarrassed in the presence of her spotty young suitor, expresses boredom, and the two snigger at Dodgson’s speech defect. Little Alice, we realise, was spiteful and self-involved, manipulative and shallow. The crimes the old woman fears facing were not Dodgson’s odd desires, but her own thoughtless cruelties.

As the moment of her acceptance speech arrives, there’s one last flashback. First, as a mortified Dodgson falls silent, Alice’s older sister takes the book and finishes the poem. Then Alice comes over to hug the writer. It’s left ambiguous if this resolution is genuine memory or consoling fiction. Merited or not, ancient Alice is forgiving herself.

Going underground

Jan Svankmajer’s 1988 Alice

When Disney reinterprets Carroll’s bestiary of fabulous portmanteau mini-monsters, it’s a Tex Avery-style parade of diverting, cute, instantly forgotten cartoon gags. In Jan Svankmajer’s stop-motion Alice (Neko z Alenky, 1988), his first full-length feature, you’re aware from the start that some Wonderlanders go without. This dank and meagre place – a labyrinth of shabby and claustrophobic Prague tenements, cellars and tunnels – speaks of hardship as well as decay. The stuff of life has its own nasty half-life: eggs break open to let loose scurrying chicken skulls; loaves sprout nails; raw meat slithers lubriciously. The crook-toothed White Rabbit hauls himself from a taxidermist’s vitrine and tugs his watch out of a sawdust-leaking chest cavity; the animals that come to his aid are mismatched bone beasts, all snapping jaws and bug eyes, dragging themselves clumsily in crowds after Alice.

Svankmajer economises with the characters. Hatter, Hare and Caterpillar are here only in very reduced circumstances: the first two in a corridor, in an endless clockwork cycle of tea and card-play, the last as a parasitic sock-worm with dentures, boring holes in his own flooring. The court is articulated pasteboard of a dour, home-painted kind, seeming to merge into the toy-theatre stage flats. Tellingly, Carroll’s two most bolshy characters, Gryphon and Cat, are absent.

Kristyna Kohoutová’s Alice is plainly, for once, a child not a teenager – and just as evidently an outsider. Her reaction shots are often close-ups on her frightened, fascinated eyes. She voices all the dialogue and narration, and frequently calls “Plee-ease! Si-ir!” after the Rabbit as he hurries away – a vain, petty, panicky semi-domesticated functionary in a fatuous, hysterical regime. As in Disney, it’s her own trial she arrives at, rather than that of the Knave of Hearts: a travesty of a procedure that includes a pre-scripted confession.

Made the year before the Berlin Wall came down, Svankmajer’s Alice is easy to read in straightforwardly refusenik terms: an absurdist regime about to be overthrown by the disenchanted young. Though of course there’s also a solidly semi-detached Czech continuum of sensibility here, harking back not just to Kafka, but to the dawn of Czech film surrealism, with Ladislaw Starewicz’s stop-motion folk tales from the 1910s, all animal skeletons and dead insects.

Louis Aragon declared that – in the imperial age of the Irish Famine, exploitative industrialisation and so-called free trade – human freedom itself “rested entirely in the frail hands of Alice”. But Breton, quoting this in his Anthology, bridled a little: to read Carroll as political satire, he insisted, was to misread him. “It is pure and simple deceit,” he wrote, “to suggest that the substitution of one regime for another could put an end to this kind of need.” The child will always be in revolt, he argued, against the governess.

As Svankmajer’s Alice herself puts it, before the opening credits: “A film for children. PERHAPS!”

Back to reality

Terry Gilliam’s 2005 Tideland

Let’s go back for a moment to that Tideland image – and two more ways in which it is Tenniel’s, even if it isn’t. There’s the matted darkness of the cross-hatching, a favoured technique that gives broodingly gothic body to the woodcut’s meticulous realism; and – not unrelated, and perhaps Tenniel’s most criticised quality – there’s the sense that the picture is a static tableau. Here’s a child hurtling down towards she knows not what – yet the image has a sense of floating, almost stately grace; her crossness is puzzlement rather than fear.

In many of Tenniel’s canonic Alice images, the main actors look as if they have been invited back to re-enact a frantic moment as a posed still – which is very effective for the allegorical political satire he was concerned with at Punch, but oddly mannerist and stylised for work directed at children. Tenniel can be charming, comical, stately, even nightmarish (Carroll nixed his Jabberwocky picture as a frontispiece for just this reason), but he really only achieves a sense of chaotic flux at the close of Through the Looking Glass, as Alice seizes the tablecloth and whirls everything to ruin, candles explode into shooting stars, cutlery coalesces into attack birds, and the feast itself rises up like a liberated, maddened zoo.

Though author and illustrator worked hard to marry images with text, Carroll was finicky and demanding, and never entirely reconciled to Tenniel’s approach. These were two shy, strong-willed artists, and Tenniel very nearly didn’t do Looking Glass – there was hesitation on both sides. Perhaps here lies the secret of the original work’s strength: there’s something about the unease of their collaboration, their silently truculent combination, that helps embed the conflict that’s so often implied, so rarely overtly manifested. Without the conservative, stately gravitas of Tenniel’s images, Carroll’s imagined spaces would present a terrifying instability: spaces where all relationships – in time, space, logic, nature and society – are undermined. But together, look and story made a book that could unite surrealists and Disney alike in admiration and imitation. It’s as if Tenniel’s images – the formally posed surfaces of his tableaux – mask what’s so unsettling in Carroll’s unhurried, gentle, clear, permanently amused prose, while simultaneously preserving it.

If the stillness of a Victorian woodcut merely postpones the moment at which the awful truth of falling bursts back out of an idea, what is it that films – which can easily depict shocking change and chaotic motion – bring to Alice? Disney revels in the playful exuberance of market culture in a golden age, turning the story into a dance – a masque, even – of people and animals as semi-abstract objects. Jonathan Miller explores how boredom and joy, triumph and melancholy, power and emptiness, lock into one another. It’s the tangle of projection, monstrous memory and impertinent desire in these most innocent relationships which fascinates Gavin Millar and Dennis Potter. And Svankmajer digs down – by means of Carroll’s own linguistic pranks and logical conundrums – beneath the foundations of his immediate social context to undermine everyone’s foundations, even yours. (“Why?” said the Caterpillar.)

In the awful moment in Wonderland when the Queen of Hearts discovers Alice in the garden and screams, “Off with her head!”, Alice replies: “Nonsense!” It’s a naming: reason’s stance against barbarism, calling out the system in its horrid absurdity. But it’s also a spell: all it takes is a little girl’s words, “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”, and reality transforms utterly, restoring order, justice, even size – and one small child as ruler of all. “The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master – that’s all.” There’s plenty left in this strange tale.

Go ask Alice: Kim Newman compares the worlds of Tim Burton and Lewis Carroll in the April 2010 issue of Sight & Sound

Alice in Wonderland (2010) reviewed by Lisa Mullen (May 2010)

Tideland reviewed by Mark Sinker (September 2006)