Primary navigation

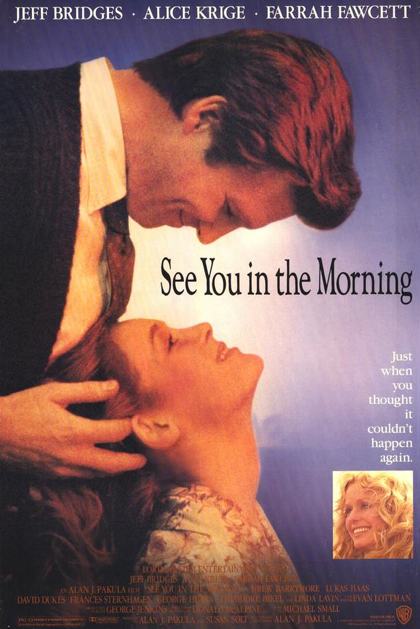

Alan J. Pakula is best known for 1970s paranoia, but See You in the Morning is a more personal later work, says Peter Tonguette

Perhaps because I first saw Alan J. Pakula’s See You in the Morning (1988) the year after my father died, I persist in thinking of it as a story of loss rather than one of divorce. Most critics tell me I’m mistaken. Time Out called it a “risible divorce drama”. The New York Times’s Vincent Canby felt the film was “about that upscale phenomenon the movie identifies as ‘musical families’.”

Actually there is reason to suppose Pakula thought of the film as I do, though he carefully conceals his intentions at first. Brief introductory sketches present two families who seem happy, until problems emerge. We meet psychiatrist Larry Livingstone (Jeff Bridges, never more appealing), who is spending a weekend at his mother-in-law’s with his wife Jo (Farrah Fawcett) and their two young children. At the end of the day, Jo soberly tells Larry that they “have to have a talk”. “What about?” he naively asks, holding her hand. “Us,” she answers. Uh-oh.

After a fade-out, the story shifts to the Goodwins, concert pianist Peter (David Dukes) and his wife Beth (Alice Krige). They also have two children, and the quartet is moving into an imposing Manhattan brownstone. Late that night, Peter sits at the piano and asks Beth, with a hint of despair, “What would you do if I could never give another concert?”

A title card appears: “Three Years Later”. The next thing we know, Larry and Beth are in bed together. A scene later, he is wishing her a happy wedding day. We assume that Beth, like Larry, has got a divorce – that her husband’s angst led to the disintegration of her marriage. But that is not the case. We next see Beth pausing to look at a group of framed photographs of Peter. The way she looks at them, and then turns away and stares off camera, is not the way a divorcee would look. What is she remembering? Not the details of a joint-custody agreement.

Through a series of intricate flashbacks, it’s revealed that Peter’s left hand became paralysed. Unable to face the prospect of career ruination, he took his own life. And so the film’s subject reveals itself. In the same series of flashbacks, Beth is seen talking to a friend in the hours after Peter’s death, when their children – Cathy (Drew Barrymore) and Petey (Lukas Haas) – bound in the door, unaware that they are suddenly fatherless. Just as Pakula only indicates Peter’s death, declining to show it, Beth hesitates in telling Petey and Cathy the news. She stands in the foyer, oblivious to the hustle and commotion of two children just home from school, as paralysed as Peter’s left hand. Cathy finally asks, “Mommy, what’s wrong?”

For Beth, Cathy and Petey, what’s wrong is much more than a mere divorce, though it was Pakula’s divorce from actress Hope Lange (and remarriage to biographer Hannah Boorstin) that inspired the movie. According to his biographer Jared Brown, See You in the Morning came about because Pakula was “determined to make a picture based on his own life” (and this is one of only a handful of films he scripted himself). He could have stopped there and made what Stanley Cavell would call a “comedy of remarriage”. Yet he went further, borrowing details from the life of Boorstin, who was a young widow when she met the director. It’s the most personal film of Pakula’s career, but its richness derives from the ways he made it not only about himself, but also about Hannah.

Though he’s most famous for his ‘paranoia trilogy’, as it’s termed – Klute (1971), The Parallax View (1974) and All the President’s Men (1976) – a Renoir-like humanist side to Pakula shines through in early films like Love and Pain and the Whole Damn Thing (1972), and is fully expressed in Sophie’s Choice (1982) and the neglected See You in the Morning, which Brown says had a “disastrous showing” at the box office.

Pakula outlines Larry and Beth’s relationship wittily. When they first meet at a party, the biggest thing they have in common is that they are both migraineurs; they walk home pale-faced and perspiring, shuffling in the dark city streets. Yet even after their marriage, the memory of Peter lingers, particularly for Peter’s children, who become latch-key kids. Cathy shoplifts from Bloomingdale’s. Petey makes a heartrending solitary trip to his father’s grave.

Larry does his best, but he is in an impossible position. As he says, “This is their father’s house… And I’m not their father.” Larry’s presence is only palatable to the extent that he can co-exist with the kids’ memory of their father, which is embodied in the brownstone they moved into before he died. When Petey learns that Larry wants to sell it, he goes from embracing his stepfather (who is nothing if not obsequious) to coldly shunning him.

As a producer, before he took up directing himself, Pakula’s most celebrated film was Robert Mulligan’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1962). Like Beth at the beginning of See You in the Morning, Mockingbird’s Atticus Finch (a widower) bears the burden of single parenthood. Remember what he tells his son Jem as he explains that he is too old to play football with him: “After all, I’m the only father you have.” When Beth brings Larry home for the first time, he overhears Petey and Cathy greeting her, and comments, “Those kids sure seem relieved to get you back home.” She replies, “When you lose one parent, you keep waiting for the other one to fall.” What painful truth is in that line, which echoes Atticus’s.

Has my sense of how accurately the film depicts the aftermath of losing a father prejudiced me in its favour? Perhaps, yet who can deny that it is among Pakula’s nimblest films, beautifully edited by his longtime colleague Evan Lottman. Cinematographer Donald McAlpine, meanwhile, proves a worthy successor to Gordon Willis, who shot Pakula’s great 1970s films.

Larry, Beth and the children do finally move house, but Pakula reminds us that the decision has a cost. Standing in the empty brownstone, Petey carves a tribute to his father (“In this house there once lived a great musician and a great man”) inside a cabinet door. We hear Larry calling for him to hurry up – the last thing he wants to do.

Early in their relationship, Beth tells Larry that he’s a funny man. Larry corrects her: “Funny weird.” See You in the Morning is funny sad. What could be sadder than a bereaved child clinging to his late father’s house?

“The screenplay is so scrupulous, so fair, so enlightened and so intelligent that real people have trouble shouldering it aside so that they can share messy human emotions. Nothing is ever quite this neat.”

— Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times, 21 April 1989

“This is so evidently ‘written’ a film… that it becomes a collection of opinions about relationships, rather than about the characters who are supposedly having them. One consequence of this over-elaborated writing is that whether the dramatic tone is benign, denunciatory or enraged, there’s a tone of blandly unvarying goodwill to the film.”

— Richard Combs, MFB, May 1990.

Death in Hebden Bridge: Jez Lewis talks to Kieron Corless about Shed Your Tears and Walk Away (June 2010)

Giant steps: David Thomson on 1970s Hollywood’s maverick talents (September 2006)

Our friends from Turin: David Forgacs on The Best of Youth (July 2004)

The Last Picture Show reviewed by Tom Milne (Monthly Film Bulletin, April 1972)