Women on film competition

Entrants’ inspirations, part one:

Actors

Margaret Sullavan in The Good Fairy (1935)

All the competition entries fit to print!

Earlier this year we held a competition for amateur female film writers, inviting them to submit a thumbnail description of a person in the world of film who is or has been an inspiration to them.

We had a terrific response – 107 entries came in, of cheeringly high general calibre and broad range – and a shortlist is now being picked over by our judging panel.

In the meantime we’re now beginning to edit and publish the best of the postbag, split into subject categories: following this page of entries about actors, we’ll be uploading submissions about directors, other off-camera crafts people, film characters and films. Check back soon for those, or follow us on Twitter or Facebook to stay informed.

» See our other entrants’ inspirations:

Directors A-H | Directors K-W | Other crew, collaborators, and critics | Characters | Films

» See our critics’ inspirations

» See our competition introduction

Thirza Wakefield, Nottingham, UK

Of actresses neglected in the age of digital video, there are none so inspirational as Margaret Sullavan (1909-1960, above). If lucky, most of us make her acquaintance – as the conceited shop-assistant, Klara Novak – in Ernst Lubitsch’s The Shop Around the Corner (1940), a film which showcases her tremendous gift for comedy but is by no means her best.

Sullavan made her first screen appearance just a decade after the popularisation of talking pictures – and how it shows. Seldom have actresses been granted so much screen time unscripted, but Sullavan warranted it: flat-featured, like a Pierrot under wet white makeup, with eyebrows now blown, now collapsible as parachutes – not the painted arabesques of her contemporaries.

As a brittle Broadway actress in The Shopworn Angel (1938), she cuts James Stewart’s Texan soldier to paper ribbons; and as the naive, newly-wed Lammchen (Little Man, What Now?, 1934) she makes hilarity out of piteousness when, side-saddle on a carousel pony and aloft of her husband, she confesses to having eaten his share of their dinner. (Only Sullavan, with her silent-era expressiveness, could justify a full five revolutions of the carousel.)

Sullavan made only 17 films – an uncommonly small estate for a leading, contracted actress in this era of Hollywood filmmaking. Taking exceptional interest in the quality and production of her work, she acquired a reputation for ‘strange behaviour’. It is apparent now that this notoriety – her so-called strangeness – had little to do with her appearing on the cover of Life in silk pyjamas and more to do with her female determination in a male-dominated industry.

It is significant – perhaps a genuine peculiarity – that Sullavan’s interventions were never intended for her own advancement. Her perseverance in the matter of hiring Dorothy Parker to rewrite the dialogue for The Moon is Our Home (1936), and in the casting of James Stewart in his first substantial role, seems to me expressive of an investment in the talents of others, a collaborative generosity, and as such is something to be commended. No, Sullavan mustn’t be forgotten, but remembered for what she most certainly was: one of the greatest and ungovernable talents of twentieth-century cinema.

Hannah Tough, Norwich, UK

Beyond the Forest (1949)

It was not until my late teens that Bette Davis’s infamous eyes met my own. So caught up in the fever of Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn, like so many of my class cohorts, walls adorned with picture postcards of the pair, I had significantly failed to notice this enigmatic wonder. Indeed, if not for my evolution into an ardent fan of the work of Pedro Almodóvar – my cinema obsessions maturing towards all things Spanish – and his tour de force All About My Mother (1999), she might have simply passed me by.

The first time I watched All About Eve (1950) in its entirety I was spellbound. Those impassioned rages, that strength of character; she was like no Hollywood actress I’d seen before. Fiction became fact, performance a reality. For me, unlike so many of her female counterparts of the Golden Age, Davis was the consummate performer.

She demanded your attention, always bewitching in challenging roles and films that were controversial for their time, but above all else she became the ultimate screen bitch. In a time when the majority of the Hollywood glitterati wanted to be painted in a positive light, forever meek and mild, Davis relished the opportunity to be a husband-stealing, money-grabbing, gun-toting, conniving, adulterous she-devil.

Her defiance of the system, with its constraining studio contracts, is demonstrative of her tenacious personality and came to define her 60-year-long career – bucking the fates of her Margo Channing and Sweet Baby Jane counterparts. The fact that she lost her battle against Warner Brothers is neither here nor there; the significance lies in her taking up the challenge. Paraphrasing Margo’s infamous speech in All About Eve, “one career all females have in common, whether we like it or not: [is] being a woman”. Davis taught us to struggle against this abiding tag.

Victoria Hayford, Luton, UK

For me, it’s not about Bette Davis’ eyes, but a memory she evoked.

It’s the mid 1970s and I am a newly arrived nine-year-old immigrant to the UK, where films appear to be on tap – or to be precise, on television. As I drink my fill of cinema, I find myself gazing upon the image of Bette Davis, whose particular performance and affectations bring to mind a dear friend I had left back in Ghana. Hereon I was hooked.

Davis’ remarkable ability simultaneously to inhabit the persona of an innocent child as well as that of an adult not only made me a little homesick, but also led me to seek out performance above all else in cinema, especially if the performance was hers. Whether in All About Eve (1950) or Jezebel (1938), Bette Davis managed to engender sympathy in me for the unsympathetic characters she often portrayed.

Therein lay Davis’ gift: there was a kind of duality to her. She embodied light and dark, the contradictions with which she breathed life into her characters, which persisted long after the end of the reel. We have all seen the parodies.

She drew from a well deep within her, the existence of which only she understood. Whatever it was, in Davis’s hands, uncompromising characters had an underlying innocence so that there was good reason to root for them. And I’m still rooting.

Gabriella Apicella, London, UK

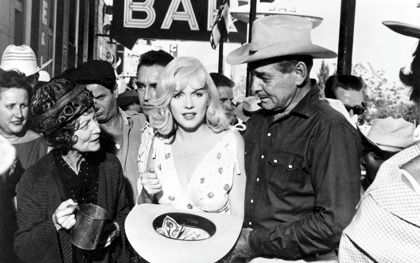

The Misfits (1961)

While channel-hopping as an eight-year-old, I suddenly became transfixed by Marilyn Monroe. She strutted into my life, sheathed in pink satin, glittering with diamonds, and I remember asking, “Why is that lady dressed like Madonna, Mummy?” And so an obsession was borne that has informed my appreciation of film ever since. I discarded my Madonna vinyl, and with the single-minded attention only a small child is capable of, set about watching all of Monroe’s films – and the films of those she worked with. Cary Grant, Lauren Bacall, John Huston and Billy Wilder were initially distinguished in my mind merely as colleagues of Monroe, and as I avidly absorbed Hollywood classics, her shadow was ever-present.

In my bleached blonde teens, I yearned to really ‘know’ Marilyn. I studied what she studied: plays, actors and techniques. They led me to Tennessee Williams, Marlon Brando and Lee Strasberg. This multi-faceted woman was leading me towards more complex films, and a deeper understanding of the power of cinema.

Although her image is no longer as prevalent on my walls, her tenacity continues to inspire me. Realising she might never escape the sexist roles 20th Century Fox required her to play, Marilyn walked out on her contract, and set up her own production company. A decade before feminism became fashionable, she asserted: “Women that seek to be equal with men lack ambition.”

Theorists attempt to categorise her: she is Laura Mulvey’s objectified ‘spectacle’, as well as Mary Ann Doane’s excessively feminine ‘masquerade’, yet neither encapsulate the ‘real’ Marilyn that many books claim to reveal. Almost 50 years after her death (14 years longer than she lived, and 40 more than she was a star) Marilyn Monroe is still the embodiment of what is fascinating about film: enigmatic, extreme, compelling and surprising.

Kezia Tooby, Penzance, UK

On one level Arnold Schwarzenegger is the epitome of an inspirational figure, a rags-to-riches story of a poor immigrant becoming the Governor of California. On a deeper level, however, I believe he represents what cinema is and should be all about: pure escapism.

I grew up watching Schwarzenegger films, so by the time I was 10 I had seen most of his best works and he became almost a father figure to me. I loved his awkwardness in Kindergarten Cop (1990) and his machismo in Commando (1985), but also the harrowing and distressing films such as Total Recall (1990) and Predator (1987, pictured). There was no censorship in my house! For me a world with Arnie in it seemed a better place.

Arnie drove women mad with his sheer physicality – a caricature of the human frame – and his strange accent, and whatever he was in became the new ‘Arnie film’. A star was born. The passion and obsession that people felt towards him was fascinating – a level of fandom that demonstrates another escape from reality.

Fast-forward 16 years, and I was completing my PGCE to teach Film Studies when my mentor revealed her own passion for Arnie. She even has an Arnie doll in her resources cupboard! In one way or another Schwarzenegger has been there at some of the most pivotal moments in my life; he has inspired me to live and breathe film.

His films are pure entertainment and spectacle, like early silent film. He has an innocence and honesty about him which contrasts with his massive body, qualities that reassure you that what you see is what you get. When hearing Arnie talk about anything he is always so passionate, and perhaps that is what I admire the most: I hope I can instil as much passion in my students as Arnold Schwarzenegger has himself.

Pauline Asper, Sedlescombe, UK

Ever since my mother took me to see Pollyanna (1960) when I was about eight, I’ve been secretly in love with Hayley Mills. The fact that a few friends said she reminded them of me – which probably had more to do with tree climbing than anything else – made me feel we had a special bond.

After that I used to eagerly await the next Hayley Mills film. We don’t do that anymore; we’re more likely to look out for the next Chris Nolan or Iñárritu movie.

Directors are now the stars and the actors their beautiful puppets. But Hayley rose at the end of the studio-contract era, and at Disney she was the engine that pulled their money train. The blurb for her 1962 film In Search of the Castaways says it all: “A Thousand Thrills – And Hayley Mills.”

What did I love about her (and I’m really talking about the way Disney depicted her; I wasn’t then into Whistle Down the Wind (1961) or The Family Way (1966))? She wasn’t really a Gidget: she didn’t have the sticky sweetness of Shirley Temple or the doe-eyed sensitivity of her contemporary Mandy Miller. She was cute rather than beautiful, but that made her seem more approachable.

And she had gumption. In The Parent Trap (1961) she played herself twice to get her estranged parents back together, and in The Moon-Spinners (1964) she suddenly acquired a cleavage and a boyfriend, and perfected her scream as she vanquished several Cretan baddies.

Then, in her last movie for Disney, That Darn Cat (1965), she and her sister are alone in the house for the summer – how grown-up! – and can even invite over members of the opposite sex. And with the help of her Siamese cat, she rescues a kidnapped bank teller. Oh joy!

That was me up there on the screen, and I’m still hoping one of my cats will come home wearing a wristwatch.

Lila Silva Foster, São Paulo, Brazil

When I first saw Rogério Sganzerla’s The Woman of Everyone (A Mulher de Todos, 1969, pictured) I was sure I would never again fall in love with a character the way I did with Angela, Flesh and Bones. She was the true essence of what I considered my feminist dilemma: she was aggressive, she kicked and slapped men, but still she was fragile; love and desire drove her crazy. Her image was gigantic, not only for the close ups the camera dedicated to her, but also for what she meant.

The greatest credit for this force on the screen definitely goes to actress Helena Ignez. Married to Glauber Rocha, but having spent most of her life with Rogério Sganzerla, she is considered a connection between cinema novo and cinema marginal, but she is surely much more than the women behind these two men.

Starting her career as an actress in Rocha’s formalist short film Patio (1959), she acted in more conventional films in the early 1960s and, in 1966, played the virginal and beautiful girl in Joaquim Pedro’s breathtaking but very controlled The Priest and The Girl (1966). Her step into cinema marginal was given with Bressane’s Cara a Cara (1967), only to explode as Janete Jane in Sganzerla’s The Red Light Bandit (1968).

Ignez was cinema marginal’s muse, but not a static one stuck on a pedestal. Not only did she act in numerous films; I’d risk saying cinema marginal wouldn’t have been possible without her. She was courageous in the way she exposed her body, the way she addressed the camera, and she had an amazing skill for improvising, making acting a fundamental creative component of the mise en scène. The aesthetic freedom for which some directors fought would not have been possible without a woman who could move so freely on the streets of Rio de Janeiro, reacting to the people walking around her and letting herself be so beautifully followed by the camera, as in Copacabana, Mon Amour (1970) as Sonia Silk.

I’ve always nurtured a special passion for Ignez’s characters, and when I think about her I always picture this interesting woman, living Brazilian Cinema with all its intensity but also sharing a very manly world, which requires a lot of strength.

I’ve seen her acting in plays, reinventing herself as a film director and striving to preserve Sganzerla’s films which, in a way, are also hers.

Lynn Stewart, Ayr, UK

Even through the barrier of a screen I know what she means. She hasn’t said anything, but I know. That look is for every woman out there who doesn’t know how to express everything that’s locked inside, struggling for release – all those words that can’t be said.

Then she speaks. The words I’ve been thinking and feeling for years. The devastating honesty, seeping out of her every pore, that sees me cross-legged on the floor, living, breathing every word with her. No longer in control of my eyes or tears, I feel years of protected emotions escape. I’ve felt these words; I’ve lived these words.

I could be talking about any of the characters she has portrayed, as she has the unfaltering ability to speak the truth, to show everything she’s trying to hide with just a look – but it’s as Kate Walker in Last Chance Harvey (2008, pictured) that I’m watching her now. She’s the epitome of crippling fear disguised by flippant cynicism.

The power of Emma Thompson’s performances, for me, don’t come from her portrayal of outwardly strong women. It’s the women who don’t know (or believe) how strong they are who resonate. She identifies with and gives meaning and a voice to those who spend their lives unheard because they just can’t find the words.

The word ‘truth’ can be overused in film, but Mamet’s insightful description of truth being “emotion withheld” relates unambiguously to Thompson’s capability to expose my deepest fears and vulnerabilities with one look – a look that speaks a thousand words.

Ellie Coggan, Warwick, UK

My first encounter with Ginger Rogers (1911–1995) was as an eager Film Studies undergraduate. I’d heard her name, of course, but could have told you nothing other than that she was the dancing partner of the legendary Fred Astaire.

Watching Swing Time (1936, above) for the first time, I marvelled not just at the breathtakingly beautiful choreography and costuming, but also at Rogers herself, effortlessly captivating and charming the audience. Her pretty, open face was able to convey the subtlest of emotions with ease, moving from deadpan indignation to suppressed longing with the mere raising of an eyebrow. She’s the only actress who can make me laugh and cry within the space of five minutes, with nothing more than the look on her face.

Unafraid to fight – whether it be for equal pay to her male counterparts, or to be seen as more than the ‘dancing girl’ – Rogers’ strength and passion is evident in her many roles, and was recognised when she won the Academy Award for Best Actress in 1940 for Kitty Foyle: The Natural History of a Woman (1940).

She battled never to be seen as just another faceless girl in sequins and feathers (ever so present in Busby Berkeley musicals of the time), and her long and varied career is undoubtedly a result of her humour, vulnerability, potency and beauty.

Bob Thaves’ famous comment on Fred Astaire – “Sure he was great, but don’t forget Ginger Rogers did everything he did… backwards, and in high heels!” – not only extols Rogers’ talent, but serves as a fitting analogy for the challenges still faced by women in the film industry.

Alison Wilde, York, UK

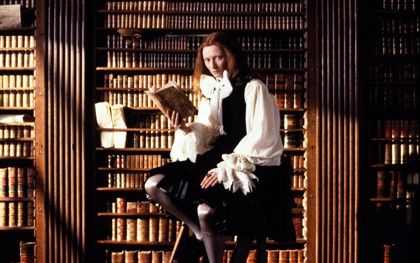

Cinema is a medium which has moved me more than any other, introducing me to people, cultures and ideas I would never have seen. Of all those who have inspired me it is Tilda Swinton who played the most significant role in helping me understand the power and potential of film.

I first saw Swinton cast as Lena, part of a love triangle in Derek Jarman’s Caravaggio (1986), a film which initiated in me an unquenchable thirst for a cinema of art and lived experience. This was the first time I yearned to be inside the film. Experienced at the time as a beautiful if messy oil painting come to life, the film introduced me to the work of Caravaggio, Swinton and Derek Jarman.

Later, after bracing myself for the adaptation of Orlando (1992, pictured) at the cinema, I found it to be the perfect vehicle for Tilda Swinton’s astonishing and androgynous beauty. The film exemplified the power that women (and feminism) can bring to cinema – and Swinton’s characterisation of Orlando and Sally Potter’s writing and direction brought Virginia Woolf’s work to a much wider film audience, adding but staying faithful to the book’s trans-gender and trans-genre origins.

Swinton has chosen roles which communicate women’s experiences in multi-dimensional ways, beyond the ‘male gaze’, in both independent and studio films. Crucially, she signposts the way for others as she proceeds, working to inspire an appreciation of art films in new audiences; she co-produced the small-scale Ballerina Ballroom Cinema of Dreams Festival in Nairn in 2008 and, as co-creator and co-manager of the 8½ Foundation, is introducing world cinema to children.

Gliding between arthouse cinema, mainstream action, thriller, comedy and children’s films, cultural politics, writing and more, Swinton has spurned convention, expanding the portrayal of women in cinema and demonstrating an unsurpassable commitment and enthusiasm for art film and audiences.

Stacey Lees, Wolverhampton, UK

Many women in film have inspired me. Perhaps the most influential is Kathryn Bigelow, the first woman to win the Academy Award for Best Director. Sofia Coppola’s intuitive screenwriting abilities have compelled me to put pen to paper. Ultimately, though, I feel respect must go to Grace Kelly for fulfilling one of my most cherished adolescent dreams: becoming a real-life princess!

In all seriousness, no screenwriter, director or actor has inspired me more than Spanish actress Penélope Cruz. Often featured in the films of my favourite director, Pedro Almodóvar (for instance All About My Mother, pictured), Cruz is an actress I both admire and envy. Effortlessly beautiful and true to her beliefs and principles, she has climbed the ladder from acting in local European hits such as Jamón, jamón (1992) to occupying a leading role in blockbusters such as the upcoming Pirates of the Caribbean 4: On Stranger Tides (2011).

First seeing her in Alejandro Amenábar’s Abre los ojos (Open Your Eyes, 1997), I found her an elegant, charming, credible actress whose performance echoed those of Golden Age legends such as Katharine Hepburn and Marilyn Monroe.

Over the past 20 years she has rarely put a foot wrong. I admire her professionalism: Cruz has mostly stayed out of Hollywood gossip tabloids, only gracing covers and conducting interviews when film marketing or charity work deemed it necessary. And she has donated not only her time but also her wealth to humanitarian work, for example helping to set up the Sabera Foundation in Calcutta for disadvantaged girls.

I was delighted that Penélope received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in April 2011. After almost two decades of unforgettable performances, it was deserved recognition.

Emma Tungatt, Christchurch, UK

Much has been published of late about Elizabeth Taylor, for the most part lavish with praise and admiration. Anecdotes about diamonds and husbands will always make for compelling reading, but there was more to her than wealth and romance: there was her everlasting impression on the screen.

She were one of the last great stars, belonging to an era of Hollywood which treated those like her with a respect and adoration befitting royalty. Indeed it was her titular performance in Cleopatra (1963) that set a new standard for stardom and influence. Her record-breaking fee set a new expectation for star salaries, whilst the glorious images of those violet eyes adorned with kohl and shadow inspired a multitude of women to emulate her idolised appearance.

Beneath the beauty, however, there was a passionate talent, and when critical voices doubted her, she gleefully silenced them with a mesmerising and visceral portrayal of Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966). Critics claimed that her youth and beauty would preclude her convincingly playing a hard-drinking and profanity-wielding fiftysomething, but the weight-gain and dowdy costumes permitted her faculties as an actress to radiate and take centre stage.

Her cinematic legacy comprised a body of over 50 films spanning more than half a century. An impressive statistic, yet the majority of those films were mere supporting characters to your greatest performance as a fabulously iconic figure of film stardom.

As a film student, I am indebted to her for providing cinema with a dedicated work-ethic and a true meaning to the word ‘stardom’. As a young woman, I cannot help but admire her for being true to herself, for holding her own in Hollywood and for displaying such generosity and humility away from the camera’s gaze. Stardom personified, she will always be a shining example of remarkable inspiration.

Thanks also to Adalgisa Serio (who hailed the worldly, womanly Anna Magnani), Emma Wang (the fearlessness of Marilyn Monroe), Gwyn Davie (Alan Rickman’s social and ethical storyteller’s conscience), Tara Gilmore (the exemplary and unmanufactured Carey Mulligan), Agne Drumelyte (Marlene Dietrich’s magnetism and charisma), Lucy Leanne Wilson (the phenomenal Angelina Jolie) and Nadege Sundi (the dexterous Whoopi Goldberg).

See also

Women on film: Critics’ inspirations: Our female writers offer thumbnail descriptions of their own film-world inspirations (March-May 2011)

Women on film online: Sophie Mayer follows the trail of female film critics into the digital realm, finding both community and quandries (April 2011)

Women on film: the ladies vanished: Hannah McGill wonders where all the women critics went – and why? (March 2011)

The Anniversary reviewed by Tim Lucas (January 2007)

The blonde: icon, stereotype, concept: Lucy Bolton wonders just what fascinates filmmakers about the blonde (February 2010)

End of Days reviewed by Mark Kermode (February 2000)

Antônio das Mortes reviewed by Michael Chanan (August 2010)

Tug of love: Nick James helps Tilda Swinton and Mark Cousins drag a cinema across the Highlands (August 2009)

Women, windmills and wedge heels: Paul Julian Smith on Pedro Almodóvar’s Volver (June 2006)