Women on film competition

Entrants’ inspirations, part four:

Other collaborators, crew – and critics

The Third Man (1949), shot by Robert Krasker

All the competition entries fit to print!

Earlier this year we held a competition for amateur female film writers, inviting them to submit a thumbnail description of a person in the world of film who is or has been an inspiration to them.

We had a terrific response – 107 entries came in, of cheeringly high general calibre and broad range – and a shortlist is now being picked over by our judging panel.

In the meantime we’re now beginning to edit and publish the best of the postbag, split into subject categories: following this page of entries about actors, we’ll be uploading submissions about directors, other off-camera crafts people, film characters and films. Check back soon for those, or follow us on Twitter or Facebook to stay informed.

» See our other entrants’ inspirations:

Actors | Directors A-H | Directors K-W | Characters | Films

» See our critics’ inspirations

» See our competition introduction

Cathy Thomas, Guernsey

The first time I saw Odd Man Out (1947), I remember thinking: this is what a film should look like. Carol Reed’s Belfast thriller about a fugitive hiding from the city’s authorities is the clear forerunner to his film noir classic The Third Man (1949, pictured above) in both story and aesthetic, and it introduced me to the thought-provoking vision of the cinematographer Robert Krasker.

In his distinctive style, startling angles and sinister shadows are revealed in even the most mundane of scenes. Krasker’s work is a testament to the visual power of cinema, making you look twice at the geometry of the world and how people fit within it. Through his eyes, bombed-out buildings, tree-lined avenues and even sewers become as unforgettable as heroes and villains. Take Brief Encounter (1945), the story of an ordinary housewife tempted by the love of a married man. The settings – railway stations, drab restaurants and cinemas – are safe, humdrum territories, and yet Krasker imbues them with a sense of irresistible darkness and violence.

Australian-born Krasker moved to England in 1932, where he took up camerawork for producer Alexander Korda on films such as The Four Feathers (1939). With the advent of the Second World War and the accompanying cinematic shift in tone from opulence to realism, Krasker turned to wartime dramas such as One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942) and The Gentle Sex (1943), the propaganda film which would form his first proper experimentation with cinematography. These intense, small-scale dramas feel like the natural precursor to the pained intimacy of Odd Man Out and his post-war successes.

While Krasker’s work dwindled after the 1960s, his 30 years behind the camera left us with a legacy that will continue to haunt the memory and jolt our expectations for decades to come.

Tania Freimuth, Southgate, UK

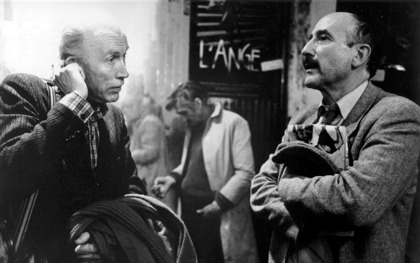

When I started reading A Man with a Camera I had no clue who the author was. But as I continued, the author’s identity became much less important than what he wrote. He believed that “the most beautiful light in the world is natural light”, and with those words I became a life-long disciple of Néstor Almendros (above right, with Eric Rohmer, left).

Though I was taught traditional methods of lighting and studio lighting, my gut instinct nagged me to use the exquisite silvery quality of natural light instead.

Twenty years later, Almendros’s devotion to and mastery of the use of natural light, wether diffused or bounced, remains the source of my inspiration.

He taught me that diagonal lines give the frame dynamics, showed me how to harness light, and his words gave me the strength to have courage in my convictions: “It is in style that we recognise the artist’s signature,” was his belief.

He created images intoned with the emotional rhythm of the script. From Kramer vs Kramer (1979), I recall the cold, flat, almost dead light in the empty home of Ted Kramer immersing me in melancholy. Almendros sought inspiration in nature using fires or kerosene lamps as sources and mirrors to bounce light into dark interiors. If he did not coin the phrase ‘magic hour’, the cinematic glory of Days of Heaven (1978) is proof that he surely knew when it was.

Even today, I believe his style would be considered unorthodox – perhaps even more so, with our heavy reliance on technology, a myriad of gadgets and post-production.

Angela Marie Trott, Dorset, UK

Never one to be seduced by the romanticism of the auteur theory, I have always been fascinated and inspired by those in the background of filmmaking, particularly the women who tirelessly and often thanklessly labour in the medium they love. In the case of Thelma Schoonmaker one may protest that three Academy Awards is surely recognition enough, and obviously a great deal more than your average female runner or script editor could ever hope for. Yet it has apparently been all too easy in the past for Schoonmaker to be casually referred to as Martin Scorsese’s editor or Michael Powell’s wife with an almost dismissive air, serving to limit her achievements outside of the context of the famous men in her life.

There is a pace and an almost musical dexterity required in skilful editing, and Schoonmaker’s command of cinematic rhythm and technical prowess made her a pioneer in a man’s field. The simple fact is that despite her frequent modesty and protestations to the contrary when interviewed, Scorsese’s films would not be hailed as the masterpieces that they are had it not been for Schoonmaker’s adept and intelligent editing. Scorsese brought these films into being, Schoonmaker brought them to life.

Schoonmaker has managed to walk the line between acknowledgement and anonymity, revered and awarded by her industry peers yet seldom hailed as the genius she should rightfully be by the vast majority of cinemagoers. For me she embodies the complex role of women in the film industry today: undeniably talented, hardworking and intelligent, yet still too often seen as a supporter; a facilitator to the real star of the show, who in this case and many others just so happens to be male.

Shelley-Ann Turner, Cambridge, UK

Marideth Sisco

– poet, singer, prolific storyteller and self-confessed hillbilly – has successfully side-stepped the Botox-driven prerequisites for women in film. Recently she lent her evocative voice to Debra Granik’s 2010 adaptation of Daniel Woodrell’s novel Winter’s Bone. As an authority on all things backwater, this passionate intellectual – who has rejected make-up for the truth of her face – was enticed out of relative obscurity by Granik to act as music consultant and featured singer in this disturbing journey into the dysfunctional and brutal world of Missouri’s isolated Ozark Mountains.Her music defines the film. It is the sinew that holds Winter’s Bone together. It is a layer of flesh that cushions the jagged and malevolent atmosphere which permeates the narrative from beginning to end. From the lingering echo of the film’s opening lullaby ‘The Missouri Waltz’ through to her appearance as matriarchal vocalist in a familial picking session midway through the film, Sisco’s presence weaves soul into the heart of the story. Her music invites empathy for characters who would otherwise barely be tolerated as human or at best be dismissed as loathsome. I found it profoundly moving that her contralto laments, coupled with the unrefined twanging of a banjo, could immerse me so deeply in the mettle of the mountains that I longed for a place I have never visited. Her music made the Ozarks feel like home.

In an industry that propagates the myth of aesthetically flawless women gift-wrapped in taut skin and with limited cognitive function, Sisco is something of an anomaly. She makes no apologies for what she is and possesses that rare sense of uncompromising self-worth, combined with intellect, soul and empathic intelligence.

Sarah McKee, Cambridge, UK

Even if you have never heard of the late Howard Ashman, you will certainly have heard his work. ‘Under the Sea’ (for which he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song in 1990), ‘Part of Your World’, ‘Beauty and the Beast’ (Best Original Song, 1992) and, my personal favourite, ‘Be Our Guest’ – the familiarity of these lyrics and their irresistible melodies (penned by Alan Menken, who still writes extensively for Disney) makes them perfect for sing-along purposes.

Between 1988 and 1991 Ashman worked as Disney’s chief lyricist. But he has also been credited with the roles of writer and executive producer, and the artistic decisions and suggestions he made have helped shape some of the most influential films of the past two decades. Unfortunately, one side-effect of the sniffed-at ‘catchy’ quality of his lyrics is that the intelligence behind their composition is rarely acknowledged.

Consider ‘The Mob Song’, which introduces the climactic scenes of Beauty and the Beast (1991). It takes Gaston about a third of the song’s length (3:30) to convince a bunch of frightened villagers that they should unite to ‘kill the beast!’ – by the end of it, they have already broken into their target’s castle. The speed at which information is conveyed and plot driven forward here is characteristic of the Ashman lyric. It is also an indication of his influence on the studio’s understanding of the entire art of film animation.

Footage from a lecture Ashman delivered to a roomful of animators in 1987 on first joining Disney (in Don Hahn’s 2009 documentary Waking Sleeping Beauty) shows him talking with incisive critical knowledge and sensitive theoretical concern about the parallel histories of musical theatre (where his career had really kicked off with Little Shop of Horrors) and music in animated film. He suggests that animation music should aim to be specifically and substantially informational, rather than ‘purely as entertainment value’.

It’s clear that Ashman actively promoted the distinctive qualities of animated film, inspiring a whole generation of Disney’s studio artists to regard their art as something special, indeed magical. Once the benefits of his guidance had become apparent – through the success of first The Little Mermaid (1989) and subsequently Beauty and the Beast – Disney was compelled to reorient its focus around its previously scorned animation division.

The lessons Ashman taught in his painfully brief, astoundingly productive period at Disney helped change the face of animation. And he did this in part through his witty and often erudite lyrics, which quietly cite Shakespeare and Cole Porter even as they make you smile and run, resolutely, through your head.

Zoe Kandyla, London, UK

With over 60 titles to her credit, Christine Vachon could be called a producing superhero. Who else’s C.V. includes “bail out actor from prison” (Kids, 1995), “find replacement financier in two days” (The Velvet Goldmine, 1998) and “battle MPAA over the certification of a rape scene” (Boys Don’t Cry, 1999)?

These are only a few examples of the challenges the founder and president of Killer Films has faced over two decades of producing often dark and controversial films on the fringe of the Hollywood system. Yet what she does is much more than the proverbial ‘dirty job’. What makes Vachon stand out is the way she invests herself in films – her audacity and faith in protecting the vision of the director no matter the risk.

Long before studios ran specialty divisions for niche films, Vachon did things differently; she undertook bold and unconventional projects based on the singularity of their voice, projects often dealing with the complexities of gender and sexuality. Todd Haynes’ Poison (1991), Tom Kalin’s Swoon (1992), Todd Solondz’s Happiness (1998) and the Oscar-nominated Boys Don’t Cry (1999) and Far From Heaven (2002) would probably never have been made without her fearless approach and bravado.

Often working with first time directors, she helped launch the careers of Mary Harron (I Shot Andy Warhol (1996), American Psycho (2002)) and John Cameron Mitchell (Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001), Rabbit Hole (2010)), and has been a driving force behind Todd Haynes’s filmmaking, in one of the strongest creative relationships in contemporary cinema.

Her work realising compelling projects and discovering new talent had an enormous impact on the American Independent and New Queer Cinema of the 90s. A leading female figure, she has changed the landscape of the film industry for women.

Today, while new platforms demand new ways of storytelling, the hunger for original filmmaking remains. Vachon – strong-minded, subversive, but first and foremost a visionary, is leading the way.

Sian Laing, Winchester, UK

“Life,” according to Joan Littlewood, my unsung hero and inspiration, “is a brief walk between two periods of darkness and anything that helps to cheer that up is valuable.”

In her heyday, the 1950s and 60s of British cinema, she galvanised British theatre. Her vision was radical and archaic. She sought to shake up the stultifying establishment by using working-class actors and her dream was to create high-class theatre for the community.

Her legacy resides in discovering new writers and encouraging idiosyncratic performers, not stars. I was fortunate enough to study at East 15 Acting School in the early 1990s, and her unorthodox training methods were still much in evidence. According to legend, the young Michael Caine was told to “Piss off to Shaftesbury Avenue. You will only ever be a star.”

Shelagh Delaney’s provocative film A Taste of Honey (1961) demonstrates Joan’s commitment to representing life’s many hues. She produced this innovative film and it captures social realism with humour. “I really do believe in the genius in every person” she once said. “And I’ve heard that greatness comes out of them, that great thing which is in people. And that’s not romanticism, d’you see?” She captures this sentiment in the film she directed, Sparrows Can’t Sing (1963), a charming and very funny comedy.

It has been said that there was a Chaplinesque solitude and jauntiness about her. There was definitely a boldness and sadness that her dream of a ‘Fun Palace’, designed to release the talent in each individual, was not realised. I applaud her feistiness and courage, and that she went to live in Paris in her later years where she was feted as a hero. And she never came back or looked back. What a pioneer!

Kerry Ryan, London, UK

As a teenager, I was given Dalí-esque nightmares by a late-night TV screening of Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945) – and the impetus to go to the local library and read up on the great director. Leafing through an old, obsequious biography, I happened on that iconic black-and-white photograph of the Master with his wife, Alma Reville. A youthful Hitchcock is pointing at someone or something out of shot, and behind him Reville leans forward, holding a script and wearing such an intense look of pure concentration that I was immediately intrigued. Who was this woman?

My search took me from silent cinema and the Hollywood studio system to five decades of feminist film theory, where I discovered that this ‘former script girl’ was actually a pioneer who, as an editor, assistant director and writer in her own right, occupied a unique position in cinema. Yet the lady’s achievements had all but vanished under a thick smog of auteur theory, despite the best efforts of daughter Patricia, a handful of critics and even Hitch himself to give Alma her due. Indeed on receipt of the American Film Institute’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 1979, the normally acknowledgement-shy Hitchcock stated that without his wife’s professional insight, he might well have ended up at the ceremony – but as one of the “slower waiters on the floor”.

What might Alma have become without Hitch? She wanted to direct until her pregnancy and her husband’s move to America changed her plans, and it’s tantalising to imagine the films that might have been had she managed to sit in the director’s chair. Certainly it’s doubtful that had she lived free of the showman’s shadow she would have spent her days as a waitress, slow or otherwise, for Hollywood’s great and louche. And who knows? We might not have had to wait 81 years for a woman to win the Oscar for Best Director.

Lee Seabourne, The Hague, The Netherlands

Photo © Ronald Grant Archive

Who is Rachael Low? She’s my inspiration.

Rachael wrote about the lives of others: pioneers of British cinema who now have their place in history. First published in 1948 and completed in 1985, her seven-volume The History of the British Film 1896-1939 is an outstanding contribution to British cinema’s narrative. She’s always there in the bibliographies – a result of her meticulous research – but Low and her seminal text seem to be overlooked in the halls of fame and her achievement little appears known outside academia.

It was serendipitous that last month I opened a link to the annual Rachael Low Lecture at the British Silent Film Festival just as I’d been reading a reference to her in Matthew Sweet’s Shepperton Babylon. He was delivering the 2011 lecture the very next day in London, but I couldn’t get there. Fate seemed to be drawing me to this woman, but bad timing was getting in the way.

This didn’t seem to be an issue for Low. While a librarian at the British Film Academy in 1948, with the support of Roger Manvell and the newly formed History Research Committee, she began her life’s work. She interviewed many of those present at the inception of the British film industry and recognised the talents of other women such as Elsie Cohen, film journalist and founder of the first arthouse cinema in Britain. She discovered and analysed primary sources and watched old films to create “a work of reference which all students of film will find indispensable”.

Yet what do we know of Low herself? Who and what inspired her and, with the exception of the annual lecture named in her honour, where is she recognised in the history of women in film? I’m inspired to find out.

Stephanie Van Schilt, Carlton North, Australia

It’s not easy to pick out one inspiration in the film world when there are so many. Anna Karina’s face at the beginning of Vivre Sa Vie (1962)? Ferris Bueller’s adolescent affirmations and MTV-bravado? Roy Andersson’s surreal flights of fancy? Henri Langlois’ lifelong dedication to the preservation of cinema history? One figure who particularly stands out, however, is Australian scholar Lesley Stern.

Reading Stern’s mind-blowing intertextual labyrinth The Scorsese Connection, I knew exactly where I wanted to be and what I wanted to be doing. The book may not be a best-selling text nor Stern a household name, but her writing is anecdotally and theoretically luminescent. The only time I put the book down was to pick up a pen, or watch a film.

Published in 1996, The Scorsese Connection is a phenomenal collection of writings that, as the title indicates, focus on Martin Scorsese’s modern genius. Stern demonstrates how meaning is created through constant connections: attuned to the personal nature of film spectatorship and criticism, she lets her memories collide with cinematic moments and philosophical ruminations as she deftly discusses Scorsese’s films. For me, the power of her writing stems from its free-associative and highly subjective quality: it moves as freely and as fluidly as the images she discusses, with her love of cinema at its core.

Stern celebrates the importance of inspiration itself, how cinematic meaning comes from specific memories and moments that grasp at, or grapple with, the heart and mind. To me, this is the biggest inspiration of all: how different moments from our lives and aspects of films can be conjoined to kindle finely formed, deeply insightful pieces of writing.

Thanks also to Nicola Balkind (who hailed the exemplary film journalism of our contributor Hannah McGill), Clara Irvine (June Mathis, a screenwriter and studio executive ahead of her time), Siobhan Burke (the oft-overlooked figure of the film composer), Emma Farley (filmdirecting4women founder Ruth Torjussen and Cornwall Film Festival director and assistant Donna Anton and Tiffany Holmes) and Christine Morrow (Dublin-based film producer Edwina Forkin).

See also

The power and the glory: Philip Kemp on Carol Reed’s underrated The Fallen Idol (August 2006)

Bayonets in paradise: Colin MacCabe on the Almendros-shot The Thin Red Line (February 1999)

Fly guy: Ian Christie on Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator (January 2005)

O Brother, Where Art Thou? reviewed by Kevin Jackson (October 2000)

Boys Don’t Cry reviewed by Xan Brooks (April 2000)

Electric ‘Underground’: Jay Weissberg on Anthony Asquith’s restored, revelatory 1928 silent (November 2009)

The best film books, by 51 critics (including mention of Rachael Low’s The History of the British Film 1896-1939) (June 2010)

Critics on critics (October 2008)