Primary navigation

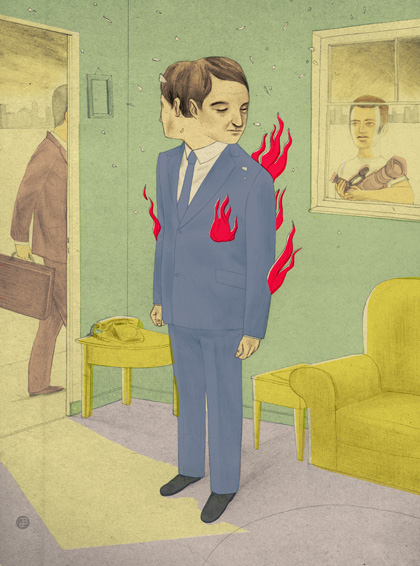

Illustration by Jonathan Burton for Sight & Sound

From ‘Cool Britannia’ to coalition cold comfort, Geoffrey Macnab unravels the circumstances surrounding the recently announced demise of the UK Film Council

On a Monday morning in late July, panicked emails started bouncing around the inboxes of film executives in Soho. A short piece on the caustic and gossipy film industry website Deadline Hollywood posted the news that the coalition government was to scrap the UK Film Council (UKFC), the public body set up by New Labour in 2000 under chief executive John Woodward.

The first reaction was one of disbelief. It was apparent that the most senior figures in the UK industry, including UKFC representatives themselves, had been caught on the hop. Producers on their summer holidays frantically called their offices to find out what had happened. Everyone knew that the Tories had long vowed to “light a bonfire of the quangos”, but for some reason no one had thought that the UKFC would be tossed into the flames.

Only a few days before the Department of Media, Culture and Sport announced the proposed abolition, UKFC representatives had happily been launching the first ‘Fully Digital Statistical Yearbook’, trumpeting the fact that UK box office had reached record levels in 2009, totalling £944 million. Ed Vaizey, minister for Culture, Communications and Creative Industries, was quoted on the UKFC’s press release applauding the UK’s thriving film industry. That was on Wednesday 21 July. The following Monday, his boss Jeremy Hunt, secretary of state for Culture, Olympics, Media and Sport, was telling the House of Commons that the government was going to axe the UKFC, citing its £3 million overheads as “money that could be better used to support film-makers”.

The following week’s debates had a surreal and contradictory feel. It wasn’t so much the announced abolition that caused consternation as the way a decision with such enormous consequences for the UK film industry had been taken without any consultation. There was an initial wave of support for the UKFC: a Facebook petition was launched to save the organisation; big-name producers spoke out on its behalf; Liam Neeson, in London for the premiere of The A-Team, described the abolition as “deplorable”; Mike Leigh called the decision “totally out of order”.

However, opinion was also swinging very sharply in the opposite direction. “Many producers and directors are delighted that it’s finally been axed,” wrote Taking Liberties producer/director Chris Atkins in the Times, claiming that the UKFC “represented the worst form of New Labour wastage”. Others couldn’t hide their Schadenfreude at the demise of an organisation that had played such a dominant role in UK film culture.

At the time of writing (early August), it is not yet clear who will take over the activities that the UKFC currently oversees, or what will happen to the money it invests (or indeed whether it may engineer an unlikely reprieve). However, the furore over the announcement underlines just how dependent on public funding the British film industry remains. It also reminds us how bitter the debates about public film policy have always been. It’s therefore timely to consider just how and why the UKFC came into existence and to assess the invariably vexed relationships between public film bodies and the industry they represent.

Contemplating the battles behind the scenes over the direction of British public film funding, it is easy to be reminded of Honoré de Balzac’s 1837 novel The Bureaucrats. Balzac’s hero Rabourdin, the head clerk in a government department, tries (and fails) to reform the administration. This über-bureaucrat’s great theory – rejected because it clashes with vested interests – is that 100 employees paid 12,000 francs would work quicker and better than 1,000 employees paid 1,200. When it comes to public funding and the British film industry, a Rabourdin-like debate has long been held about which model works best. Is it better to have one big organisation handing out the money, or to invest via a number of gatekeepers? How well should these gatekeepers be remunerated?

What is clear is that the UKFC is an invention of the National Lottery era. We are so accustomed now to lottery investment that it’s easy to forget the transformative effect it initially had. In spring 1995, Arts Council England (ACE) announced that it was going to be investing in British film-making through its newly formed National Lottery Film Department. Between April 1995 and May 1999, when ACE was responsible for the allocation of lottery funds to British films, it pumped £67 million into 79 features and £1.4 million into 49 short films. It also invested £95 million in the three UK production franchises awarded to DNA, Pathé and the Film Consortium in May 1997. At the time Carolyn Lambert, director of lottery film, insisted that ACE wasn’t trying to usurp the role played by other public film funders such as British Screen Finance, the BFI Production Board and the European Co-Production Fund. But ACE inevitably had a destabilising impact on film funding and those bodies all disappeared within five years.

Hilary and Jackie

The lottery bonanza didn’t have quite the anticipated effect, however. It quickly became apparent that ACE itself had reservations about many of the films it was backing. “Some films that we have put money into are pretty weak,” Lambert commented in 1998. “British scripts go into production too soon. The typical four drafts – if you’re very lucky – are simply not enough for a polished product.” Complaining about the high proportion of adaptations of classic novels submitted for funding, she was quoted as saying that in future the emphasis would be on original scripts: “A new Full Monty rather than another Jane Austen.”

By the time the UKFC came into existence – intially just as the Film Council – in 2000, there was widespread outcry (orchestrated by critics such as the Daily Mail’s Christopher Tookey and the Evening Standard’s Alexander Walker) about the investment of any public money in the film industry. The three lottery franchises were failing to live up to expectations. ACE’s Lottery Film Board was thought by many to have lost the plot. It had been hamstrung throughout its short-lived career by the curse of ‘additionality’, the clause that restricted it to backing only projects that couldn’t find their funding on the open market.

Though there were well-received ACE-backed films, such as Phil Agland’s Thomas Hardy adaptation The Woodlanders (1997) and Anand Tucker’s Hilary and Jackie (1998), it was nevertheless open season on lottery films in much of the UK press. Walker took to listing the precise amounts of public money invested in British films, noting, for example, that Julien Temple’s Pandaemonium (2000) – a film he described as “among the most vulgar travesties of English literature that I’ve seen in years” – received £656,094 of lottery money. Walker also complained about the way huge amounts of public money were spent without anyone seemingly being accountable for the losses incurred. As he put it: “Lottery money is transparent when grants are announced, opaque when invested in films and invisible once the dismal box-office results come in.”

In the face of such opposition, ACE seemed surprisingly eager to throw in the towel. As one well-placed observer noted, its ready acceptance of the tabloids’ criticism did the film-makers it supported no favours: “The Arts Council’s spinelessness contributed to the sense among many serious film-makers, who knew their work was regarded with contempt by the [Alan] Parker-Woodward persuasion, that they were about to be seriously disenfranchised.” As tabloid attacks on lottery-funded films continued, projects backed by British Screen Finance and by the BFI were caught in the crossfire. British Screen under Simon Perry had supported such films as The Crying Game, Orlando, Naked, Land and Freedom, Sliding Doors and Hilary and Jackie. It also administered the European Co-Production Fund – a UK-based initiative that had received a grant of £5 million (spread over 1991 to 1994) from the Conservative government to “promote collaboration between British film producers and other film producers in the European Union”. The BFI’s production arm, meanwhile, had backed innovative and experimental film-makers such as Peter Greenaway, Derek Jarman, Bill Douglas, Patrick Keiller and Terence Davies. Both bodies would disappear as we entered the brave new world of the UKFC.

Ironically, where in the dark days of the 1980s and early 1990s British producers had struggled to raise any financing for their films, by the end of the 1990s the charge was that it was too easy. At the same time as lottery money was pouring into British film production with such mixed results, new incentives were being introduced for British producers. On its election in 1997, New Labour introduced tax breaks to film-makers. Section 48 tax relief allowed producers to write off 100 per cent of first-year production costs on movies budgeted at under £15 million. Section 42 allowed investment in bigger-budget movies to be written off over three years. The new tax breaks had one much-desired effect: they brought into the industry the financiers who had for so long shunned British movies as potential investments. City money was now readily available for qualifying films; the downside was that the market suddenly became flooded with lowish-budget British movies that no one wanted to see.

At one stage in the late 1990s, according to Screen Finance, close to 60 per cent of the British films going into production didn’t have distribution attached. For many investors this was a matter of indifference: they received their tax write-off whatever the film made – or didn’t make – at the box office. There were claims that films were being green-lit prematurely to meet end-of-tax-year deadlines. It was also alleged that the tax breaks introduced to stimulate UK film-making were being used for everything from TV soap operas to weather broadcasts and kids’ shows. Financiers were factoring in cast and crew deferrals worth much more than their films’ cash budgets and then claiming tax relief on the total amount.

Four Weddings and a Funeral

In the summer of 1998, the Labour government’s then culture secretary, Chris Smith, called for film to be centralised in one institution. “There were about four or five different agencies all dealing with some aspect of the film industry and film-making, as well as some residual work being done through the Arts Council,” Lord Smith recalls. “I felt there was a need for two things. One was much greater coherence – hence the idea of bringing everything under one roof. Second, I wanted to make sure that we brought what one might call the artistic side of British film-making together with the more commercial side so that each could usefully feed off the other.” Smith wanted a “body with real clout” that could fund film-making and film initiatives while also pressing the government on the issues that mattered most for the film industry.

‘The Bigger Picture’, a report by the government’s Film Policy Review Group published in 1998, was strongly influenced by the example of PolyGram Filmed Entertainment, by some stretch the most successful British film company of the 1990s (albeit a Dutch-owned one). The UK industry, the report suggested, was production-led and fragmented. Britain had an undercapitalised cottage industry in which producers had no meaningful relationship with distributors. Unable to finance slates of films, production companies lurched from one half-baked project to the next. “In many cases, they [producers] have no option but to proceed to principal photography in order to unlock a portion of their fees,” the report suggested. “This contrasts markedly with Hollywood, where the majors have the resources to go through many more drafts of scripts, or to write off projects which, despite investment in development, do not come up to scratch.”

The combination of tax funding and the ACE’s ‘lotto lolly’ had made it relatively easy for producers to get their movies into production, but too many were operating in a vacuum, without any prospect of getting their films into cinemas – or indeed profit. ‘The Bigger Picture’ advocated creating “distribution-led, integrated structures” – in other words, forming more companies like PolyGram. It also came up with various initiatives to boost training and development. Many of these ideas were later embraced by the UKFC.

Depending on who you talk to, PolyGram was either the boldest, most imaginative British company since the days of Alexander Korda or an overreaching organisation that was bound to fail. It was one of many attempts to create a pan-European company with the marketing and distribution muscle of the Hollywood majors. In 1994 the company backed Mike Newell’s runaway box-office success Four Weddings and a Funeral, which made an international star of Hugh Grant. Unusually for a British film, Four Weddings opened first in the US in the spring. By the time it was released in Britain that summer it already had the validation of American approval, a success attributed to PolyGram’s strength in the US market. (Working Title, the production company behind Four Weddings, was then owned by PolyGram.)

Trainspotting

In February 1996, Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting, another PolyGram film, was released in the UK. PolyGram signed up Britpop bands for its soundtrack and promoted the film as if it were a pop album. The company already had experience of distributing US indie pics-with-attitude such as Reservoir Dogs and The Usual Suspects, and brought the same chutzpah and energy to the British film. The contrast with lottery-backed heritage movies was glaring. This was the age of ‘Cool Briannia’, and Trainspotting and Four Weddings were the two films most closely identified with it. When the first Blair Labour government was elected it flagged up the ‘creative industries’ as a major driver of the UK economy.

It was against this background that the UKFC was set up in 2000, under chief executive John Woodward and chairman Alan Parker (who had both filled the same roles at the BFI). “The Film Council will help to finance popular films that the British public will go and see in the multiplexes on Friday night. Films that entertain people and make them feel good,” John Woodward, UKFC chief executive, told the Guardian in 2000.

Ironically, at the very time PolyGram-influenced thinking was driving government film policy, PolyGram itself had been falling apart – in 1999 its owners Philips sold it to Seagram, owners of Universal. Nevertheless, its profound effect on the UKFC’s early philosophy was reflected in a speech by chairman Alan Parker in November 2002 that was notable for its deference towards the US studio system: “Film is the key driver of the creative industries,” Parker declared, “the same creative industries that in the US are already worth half a trillion dollars annually.” He went on to advocate that the UK strengthen its traditional links with the US industry at every level. It was time for the Brits “to raise the bar of our ambitions,” Parker said. Public subsidy for production wouldn’t be enough to form the basis of a successful film industry; nor could tax breaks be relied upon. What was needed was access to international distribution.

“We need to abandon forever the ‘little England’ vision of a UK industry comprised of small British film companies delivering parochial British films,” Parker declared, using deliberately provocative rhetoric. “That, I suspect, is what many people think of when they talk of a ‘sustainable’ British film industry. Well, it’s time for a reality check. That ‘British’ film industry never existed, and in the brutal age of global capitalism, it never will.

“We’ve had seven years of lottery subsidy, and five years of a production-focused tax break,” Parker continued. “Neither has delivered the structural changes that we need in order to deliver the consistent performance and growth to prevent a crisis every five years.” Distribution pull, not production push was his solution for achieving the long-dreamed-of goal of a sustainable UK industry. He called for a revision of the way in which British films were defined to “reflect the fact that actual production increasingly will take place in countries with a lower cost base than ours”.

Sex Lives of the Potato Men

It was probably not Parker’s fault that his speech proved wildly off-beam. Over the following years, the UKFC’s self-set goal of “building a sustainable industry” was quietly downplayed. In the 2009 consultation document ‘UK Film: Digital innovation and creative excellence’, the UKFC set its strategic objective for the next three years as being “to help ensure a successful transition into the digital age for UK film”. This was rather more modest than its original goals. In the foreword to the report, the chief executive officer (still John Woodward) referred to “the fragmented UK film sector, comprised mainly of small companies”. So after ten years, that early aim of creating big, vertically integrated companies with access to international distribution clearly hadn’t been achieved.

Alongside its successes, the UKFC endured its share of mishaps and embarrassments. It was supposed to overhaul the investment of lottery funds in production and thereby protect film-makers from the tabloid attack dogs. However, after the UKFC invested close to £1 million in the comedy Sex Lives of the Potato Men, “one of the two most nauseous films ever made” in the opinion of the Times, the chorus of derision was louder than ever. Early that same year, meanwhile, producers were upset by the UKFC’s failure to prepare them for sudden tax-law changes that led to several films’ financing collapsing overnight, prompting questions about the organisation’s fundamental purpose. Former PolyGram boss Michael Kuhn called the UKFC a “Janus-like” body, “representing the industry to the government but not representing us” [producers] and “representing government to the industry but helpless in light of, and blindsided by, recent tax changes”.

“We sit between government and industry, but we are not an industry body,” Woodward told a producers’ conference in London in 2005. “We are a government body. We’re owned by the government. Our salaries are paid by the government… Our job is not to listen to the film industry and say, ‘Is that what you want? OK, we’re going to now go to the government and say this is what the film industry wants you to do.’ If anybody thinks that, they are totally and utterly wrong. Our job is to give the government impartial advice about what is sensible… and to try and mediate between the aspirations and ambitions of a rapacious film industry and what is achievable and realistic.”

The UKFC, he pointed out, also looks after lottery money and makes investment strategy. At the time of its launch, the UKFC set a target that 20 per cent of each of its funds would be used for European co-productions. This was not a target it paid much attention to. Thanks to Section 48 and Section 42, the UK was highly desirable as a co-production partner and so it hardly seemed necessary to spend lottery money on minority co-productions. When the new UK tax credit was introduced in 2006 and Section 42 and Section 48 were scrapped, UK co-production figures plummeted. The British had withdrawn from Eurimages, the Council of Europe fund for co-production, in 1996. A decade later, British producers had next to nothing to offer European partners financially.

Vera Drake

Contemplating a decade of UKFC investment in film production, it is easy to pinpoint the successful films that have been backed: award winners such as The Wind That Shakes the Barley, Vera Drake and The Magdalene Sisters; critical and popular successes such as Gosford Park and Touching the Void. It’s an impressive enough record – but, it could be argued, so were those of British Screen and the BFI Production Board.

“The real endemic problems of the British film industry are never going to be solved by chucking £50 million at it,” John Woodward commented in 2000, just as the UKFC was coming into existence. That has proved true. Nine years on, he was still striking a bullish note about the agency’s achievements: “No doubt about it – since our creation, the landscape for film in the UK has changed for the better,” he wrote in his foreword to ‘UK Film: Digital innovation and creative excellence’. That is arguably true too.

We’re now at the end of a cycle. The UKFC is faced with abolition and the public film-funding model will almost certainly have to be redesigned. It was telling that in April 2010 the UKFC announced that its current chairman Tim Bevan would chair a think tank to identify ways of “growing UK companies of scale”. This, of course, was exactly the goal back in 1997, when the government awarded the three lottery-backed franchises worth more than £90 million over six years. The truth is that in 2010, over half of independent production companies are loss-making.

“The Film Council has done a fantastic job in many ways, building audiences, getting new talent, funding film,” John McVay, head of producers’ trade body Pact, told Screen International this spring. “What has not happened in the last ten years is that we haven’t seen the emergence of commercially sustainable UK film production companies.” Pact estimates that £100 million is currently invested by public sources in UK film production each year, yet “producers of even the most successful films remain reliant on public funding and typically struggle to share in revenues from even hit films.” What is painfully apparent is that, even with the bonanza of lottery cash, the UKFC hasn’t been able to change the dire financial plight of producers.

Maybe the Brits simply haven’t appreciated how well the Labour government treated the film industry. “I think [former Conservative Prime Minister] John Major did a very important thing in allowing film to become one of the claimants of lottery money,” observes Lord Puttnam CBE. “That was a huge step in the right direction.” Puttnam adds that after Major lost power, the Labour government proved a “fantastic friend to the film industry”. The question now is whether the new Cameron administration will continue in the same way. At least in the short term, lottery money is being diverted to the Olympics, but ministers in the new government have insisted they’re committed to supporting film.

In his capacity as president of the Film Distributors’ Association, Puttnam made a statement about the proposed abolition of the UKFC, describing the organisation as “a layer of strategic glue that’s helped bind the many parts of our disparate industry together”. It’s an apt metaphor. What is also clear is that there is no magic solution for binding the UK film industry together. Whatever happens now, whoever is put in charge of the purse strings, the debate about public film funding is likely to remain as vexed and fractious as ever.

Producer Keith Griffith and archivist Dylan Cave respond to the abolition of the UK Film Council in the October 2010 issue of Sight & Sound

The end of prestige?: Nick James reads the entrails of 'quality' cinema in the wake of the UK Film Council and Miramax Films (online, August 2010)

Rough cuts: Nick James warns against axing our already struggling art-film sector (editorial, July 2010)

In bed with the Film Council: Nick James on the new screen agency’s clean-slate intentions (January 2001)

Digital deluge: what are the consequences for British cultural films if DV is the only option, asks Nick James? (October 2001)

Beyond the horizon: Mark Cousins on Peter Sellers’ New Crowned Hope commissions (rejected by the UK Film Council, Channel 4 and the BBC) (July 2007)

Nowhere Boy reviewed by Trevor Johnston (January 2010)

Romantic setting: Jane Campion talks to Nick James about Bright Star (December 2009)

Better Things reviewed by Jonathan Romney (February 2009)

Man on Wire reviewed by Catherine Wheatley (August 2008)

A royal rumpus: Nick James sees Steve McQueen’s Hunger at the Cannes Film Festival (July 2008)

London to Brighton reviewed by Michael Brooke (December 2006)

Red Road previewed by Hannah McGill (November 2006)

The Wind That Shakes the Barley reviewed by Edward Lawrenson (July 2006)

Ballad of the wild boys: The Proposition’s John Hillcoat and Nick Cave talk to Nick Roddick (March 2006)

Vera Drake reviewed by Ryan Gilbey (January 2005)

The Girl with a Pearl Earring reviewed by David Jays (February 2004)

Touching the Void reviewed by Richard Falcon (January 2004)

Young Adam reviewed by Philip Kemp (October 2003)