Festivals

Cannes Film Festival 2011:

The Sight & Sound blog

Awards reaction

Nick James, 22 May

Wow again. What a relief. Robert De Niro’s jury do the right thing: the Palme d’Or goes to The Tree of Life. The Grand Prix is shared between Nuri Bilge Ceylan (Once Upon a Time in Anatolia) and Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne (The Kid on a Bike).

What this suggests once again is that it doesn’t pay to be too entertaining at Cannes. Michel Hazanavicius’s The Artist, Aki Kaurismäki’s Le Havre and Pedro Almodóvar’s The Skin That I Live In gave us the most fun, but didn’t get much of a look in when it came to prizes, the Best Actor award to Jean Dujardin from The Artist (pictured, with Bérénice Bejo) being the exception. However, Kirsten Dunst getting Best Actress is maybe the reason why Lars von Trier’s Melancholia itself didn’t get kicked out like its director.

Wish I’d been there to hear De Niro’s French. (You can hear it 6½ minutes in to the video on the festival’s homepage.)

Wow and what next?

Nick James, 22 May

As I write this, it’s early morning on Cannes prize day. For me the rapture has already happened – it was being at this festival in a glorious year. Now, as I’m back at home in London falling asleep, waking and falling asleep again, the one omnipresent thought I have is that it will be a huge injustice today if Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (pictured) doesn’t win the Palme d’Or. I say this not because I think it was the ‘best film’ – this hymn-like celebration of creation and destruction seems almost allergic to drama as you watch it – but because it was so overwhelmingly the event of the festival.

This remains true despite all of Lars von Trier’s sad efforts to make it not so. One can see von Trier as the rogue planet Melancholia and Malick as the spinning earth but collision was avoided because von Trier proved to be the fly-by rather than the end of days he’d like to be. I’ve written before in the magazine that the ‘best film’ accolade is no longer the point at Cannes – the ‘wow’ factor is the goal now, and Malick’s film wowed more than any other.

That said, there is a worry for cinephiles coming off the back of this festival – the lack of a next set of authoritative auteurs. For this really has been the Cannes of the usual suspects. Nanni Moretti was the only regular to turn in a weak film in Habemus Papam and even that had a wonderful last 20 minutes.

Of the newer talents only Michel Hazanavicius, director of The Artist, is remotely in the same league. There is so much to be said for experience in this field. The absolute verve and confidence with which the Dardenne brothers, Aki Kaurismäki, Pedro Almodóvar, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Terrence Malick, von Trier and Paolo Sorrentino make films has been hard won, but they need pressure from putative replacements.

I was most impressed by American indie films from Sean Durkin (Martha Mary May Marlene – in Un Certain Regard) and Jeff Nichols (Take Shelter – in the Critics week), Australian Justin Kurzel’s Snowtown was truly powerful and Na Hong Jin’s phenomenal Korean chase thriller The Yellow Sea (aka The Murderer – in Un Certain Regard). But these films lack the trademark distinctiveness of the veterans. It will come only if such new talents get plenty of opportunities to hone their ideas and craft.

My winner: The Tree of Life (Malick)

Likely winner: The Artist (Hazanavicius) or Le Havre (Kaurismäki) or (outside chance) The Skin That I Live In (Almodóvar)

‘Best film’: probably Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, but I’d like to see it again before making up my mind.

High score draw?

Geoff Andrew, 21 May

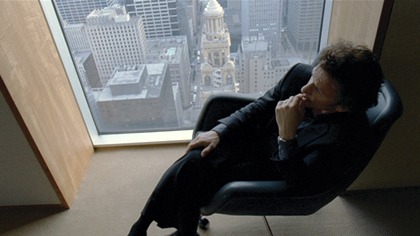

Sex ’n’ religion ’n’ politics… Well, the Cannes competition could have made space for drugs ’n’ rock ’n’ roll, and almost did so with Paolo Sorrentino’s This Must Be the Place (Italy/France/Ireland), except that Sean Penn’s ageing rock-star protagonist (pictured above), by the time of the movie’s beginning, has long ago given up his career and the habits that went with it for a life of quiet seclusion in Dublin.

So the climax to the contest – one can’t really count Radu Mihaileanu’s relatively minor The Source (La Source des femmes, France/Morocco/ Belgium/Italy) – came in the form of a search for the Truth: namely, a murder investigation, in Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Bir Zamanlar Anadolu’da, Turkey/Bosnia-Herzegovina). Of course, it being a film by Nuri Bilge Ceylan, the search ends on a note of skeptical uncertainly – wholly fitting for a competition that included an unusually large number of good or very good films, no outright turkeys, and few real surprises.

In short, as I write, anything could win – and I’ve been to Cannes often enough not to venture overly bold predictions; one never knows what the jurors will like, still less how they’ll negotiate with one another (wouldn’t you love to be able to listen in on Robert De Niro and Mahamet-Saleh Haroun arguing the toss?).

But I can at least proffer my own best-of-the-fest list; they are more or less in order of preference, and the first is the one I’d most like to see win the Palme d’Or:

- Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Ceylan)

- Footnote (Joseph Cedar)

- The Kid with a Bike (Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne)

- Le Havre (Aki Kaurismäki)

- The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius)

- The Skin That I Live In (Pedro Almodóvar)

- This Must Be the Place (Sorrentino)

- The Tree of Life (Terrence Malick)

Round the slow campfire

Nick James, 21 May

The last Friday evening competition slot in Cannes is a difficult one for journalists, nearly all of whom are in a state of utter exhaustion. But it’s thought to be a canny slot from which to influence the jury, who (presumably) are much better rested and in a state of excitement and anticipation about the closing weekend.

Which is both good and bad news for Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s super-subtle, ultra-slow-burn of a crime film Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Bir Zamanlar Anadolu’da, Turkey/Bosnia-Herzegovina). This somewhat reticent tale requires one’s concentrative powers to be at their sharpest as we witness a three-vehicle police team being led through the night by the perpetrators of a murder to locate the corpse they buried somewhere out in the anonymous and hard-to-distinguish rural hills.

A change in style for Ceylan in its seeming reluctance to bait and hook its audience too soon, this is a rumination on investigative storytelling told as if round a campfire. The drama is relayed from character to character – explosive veteran cop to terrified killer, troubled investigator and haunted doctor.

Ceylan saves and delivers his jewel-like surprises with the precision of a Chekov. But whether audiences will stay with this extraordinary tour de force long enough or whether Robert De Niro’s jury has the patience to soak in its exquisite details remains to be seen.

More on Jafar Panahi’s This is Not a Film

Gabe Klinger, 20 May

The disingenuously titled This is Not a Film, Jafar Panahi’s surprise entry to the festival (co-directed with Mojtaba Mirtahmasb), is by its very nature one of the most vital films in Cannes. Simply made but far from simple, it’s a radical cri de coeur from a filmmaker whose itch to express himself remains intact despite efforts by Iranian authorities to silence him. As Panahi makes unambiguous in the film through candid mobile-phone conversations, he will likely go to jail. This devastating reality does not seem to interfere with his capacity to reflect lucidly on his filmmaking process in relation to Iranian censorship, and to speak playfully and generously with the (few) people around him (his wife and daughter are curiously absent from the film, though they were in attendance at the official screening here in Cannes).

The film reaches an unexpected crescendo in the final ten minutes or so, as Panahi follows his doorman on rubbish-collection routine. Unexpectedly cathartic, this sequence is a powerful testament to Panahi’s filmmaking dexterity, his capacity to find poetic substance in the most ordinary of situations. This is Not a Film is built from nothing, and yet every moment has a powerful urgency to it.

The way the film came to be in the festival is still unclear. At the screening, Thierry Fremaux mentioned that This is Not a Film was smuggled out of Iran using “high technology.”

The comment turns out to be facetious. Afterwards I ran into a festival staffer who said that, in fact, the digital file containing the film was put in a pen drive that made it out of Iran’s borders in a remarkably – almost unbelievably – simple vessel: a cake.

The moon in May

Agnieszka Gratza, 20 May

Heavenly bodies of one kind or another loomed large in this year’s main competition, most obviously in Lars von Trier’s Melancholia and Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life but also in Naomi Kawase’s Hanezu (Japan), which features several close-ups of a misty moon threatening in its sheer bulk. Whether or not the prevalence of this ponderous motif reflects the current economic doom and gloom is open to debate. On a brighter note, George Méliès’s delightful 16-minute-long Le Voyage sur la lune (A Trip to the Moon) of 1902, superbly restored, was among the highlights of the Cannes Classics strand.

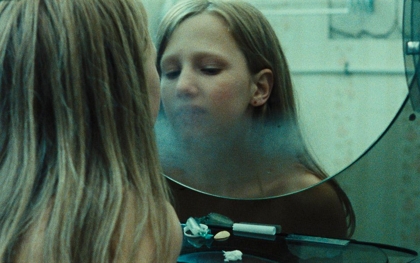

Resolutely down-to-earth despite its ethereal title, Alice Rohrwacher’s feature debut Corpo celeste (Heavenly Body, Italy/Swiss/France, pictured above), premiered at the Directors’ Fornight and awarded Cannes’ Città di Roma prize for emerging cinema from Latin countries, offers yet another slant on this notion, this time metaphorical. A coming-of-age story doubling as a spiritual quest, the film is set in Calabria, like last year’s festival hit Le quattro volte. Rohrwacher’s sensitive portrayal of local realities steers clear of stereotypes and captures something of the region’s gritty appeal through the eyes of a 13-year-old girl, Marta.

Rohrwacher elicits yet another captivating performance by a young actor (a signature note of this year’s festival) from Yile Vianello, whose blond hair and otherworldly beauty set her apart from her peers. Rohrwacher apparently eventually found the actress she had been looking for in a sealed-off, Shangri-La-like community in central Italy. The title alludes at once to Marta’s pale body, on the cusp of womanhood, the body of Christ, and earth itself, viewed from outer space as a heavenly body among many.

Also included in the Fortnight, Chatrak (Mushrooms, India/France) by Vimukthi Jayasundara – the Sri Lankan director whose first feature, The Forsaken Land, won the Caméra d’Or in 2005 – makes for demanding viewing. It takes a while to work out how the different story strands hang together as the film flits back and forth between urban and rural scenes, focusing in turn on the trials of an architect who returns to Calcutta after a prolonged absence and of his wayward brother, turned enfant sauvage after years of living in the forest. Disconcerting though the plot may at least initially be, the film has its wild as well as some comic moments that soon win the viewer over.

Political animals

Geoff Andrew, 19 May

There’s been sex, there’s been religion, so perhaps it was inevitable that there’d eventually be politics in Cannes. Of course, one can argue that every film is political, but politics as thematic content had kept a low profile at the start of the festival.

But in the last few days things have picked up on that front, at least in terms of homegrown French cinema: Xavier Durringer’s La Conquête (The Conquest) is a film about the rise of Sarkozy, while Alain Cavalier’s Pater (Father) has the diarist-director and French star Vincent Lindon indulging in some informal improvisations with the former in the role of the French president and the latter as a politician he’s considering taking on as his new prime minister. And then there’s Pierre Schoeller’s L’Exercice de l’état (The Minister, pictured above), a tale of idealism and compromise in which the great Olivier Gourmet plays a French Minister of Transport fighting a plan to privatise the rail stations.

Of course, all these films were somewhat overshadowed by a certain Danish auteur’s characteristically provocative comments about Hitler and Nazism which, notwithstanding a prompt apology, resulted in the Festival’s board declaring him persona non grata.

Unfortunately such controversy also distracted attention away from one of the most unexpected films to make it to the Croisette: This Is Not a Film (In Film Nist), co-directed by Mojtaba Mirtahmasb and Jafar Panahi (pictured, above right), who has famously been sentenced by the Iranian judiciary to six years imprisonment and a 20-year ban on making movies. Essentially, it depicts a day in Panahi’s life at home; but the closing credits are testament to the very real courage involved in making the film and in having it screened at the world’s foremost international festival. Described as “An effort by” its two creators, it is dedicated to Iranian filmmakers and offers thanks to a number of people who supported and helped in the making of the film, all of whom are represented by “…… ……”

Now that’s what I call a provocation…

The Tree of Life: three anecdotes

Gabe Klinger, 19 May

Is it already passé to talk about Terrence Malick? While Cannes is understandably obsessed with Lars von Trier at the moment, I thought I’d return to the true auteur star of the festival…

1.

At the official screening of The Tree of Life on Monday, cameras turned to Sean Penn, Jessica Chastain and Brad Pitt while their director was nowhere to be seen. The three actors – stoic, upright, barely cracking a smile (consistent with the expectation that we were about to see a serious work of art) – waved for a bit and took their seats; a plain-clothed Mick Jagger strolled by, hardly noticed; and the show was ready to start. At the end the same ritual was repeated, except this time Thierry Fremaux appeared in the centre aisle to introduce a certain someone…

It took a few beats for the audience to realise who he was, but when they did the applause intensified a few notches. Pitt and Chastain were visibly moved to see the greyed, portly Malick in attendance, and were flabbergasted as he darted out of the room as quickly as he’d come. The cameramen in the auditorium had been instructed to put their equipment down as the filmmaker entered, so if the video is ever released, the Lumière theatre’s rug will briefly appear as the star of the evening.

2.

Outside the Palais Stephanie on Wednesday, I ran into a member of the Official Competition jury. The person – who, bien sûr, will remain anonymous – asked me how I was. “Still shivering from the Malick,” I replied; “Me too!” responded the juror enthusiastically (before adding the obligatory “Oops! I should keep my mouth shut” expression). Plugging away, I asked Mr/Mrs Juror what the chances are of The Tree of Life winning something. The answer was not promising: “It’s going to be difficult.”

3.

Some Malick crew members have been hanging out on the Croisette. According to one, who flashed me a few snaps of the mysterious filmmaker from his iPhone, The Tree of Life was shot four years ago and cost more than $150 million. I’m not sure if this is consistent with other reports that are out, but it’s fascinating anyway.

Lately I’m of the opinion that the less we know about Malick’s productions, the better. It was more than ten years after The Thin Red Line that the film’s editors, for example, gave some insight into their experience of its making on the recent Criterion Collection release. My favourite story related in those DVD bonuses is about Malick spending most of the time while he was still engaged in the editing of the film listening to Green Day albums on a Sony Walkman… Hardly the Malick that we imagine when we see something as lyrical and delicate as The Tree of Life.

Prediction time

The usual suspect? Illustration by Simon Cooper for Sight & Sound

Nick James, 19 May

Here’s a sure bet for Cannes: though it’s not yet been kicked out, Melancholia will not win the Palme d’Or. Lars von Trier may say (as reported in a Danish newspaper) that he is proud to have been declared “persona non grata” by the festival’s board after his foolish remarks about Nazis and Hitler, but it’s clear that his inveterate provocations have this time gone too far. (Indeed one might infer from the severity of the response that the festival may have long grown tired of his antics.) It seems likely that von Trier, realising Melancholia had shocked no-one, was determined to be provocative at his press conference and just let his mouth run. He’s right to claim, in the same newspaper, that the Vichy years have made France super-sensitive to the issue, but that’s hardly an excuse. If not his own knowledge of history, then the John Galliano case alone should have made him pause before pushing the ‘joke’ anti-semite button.

So, to switch to more trivial matters, the ground is slightly clearer as far as the Cannes competition is concerned. At this time, given the wave of interest it’s caused around the world, you’d think Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life was a shoe-in, but it’s a very divisive piece and I’m not sure there’s enough acting in it for Robert De Niro’s actor-heavy jury.

I’d also say, regretfully, that there’s little chance of Lynne Ramsay’s vivid We Need to Talk About Kevin winning it – it’s the usual fate of the first films out of the traps to be ignored (it seems like we saw it years ago) – though I could be wrong. Ken Loach’s The Wind That Shakes the Barley won from the front, so to speak, a few years ago.

Pedro Almodóvar has never won the Palme and his thrilling The Skin That I Live In, which we saw this morning, is more than up to his usual high standard, though I have a feeling it’s too knowing a melodramatic black comedy to seal the prize. The gobsmacking fact of Aki Kaurismäki having made a rollicking romantic comedy in Le Havre that might even cross over to a popular audience makes it a front runner. And the Dardennes’s The Kid with a Bike is just as impeccable a job as either of the two films that have won the Palme for them before.

It is rumoured by some that the prize is almost certainly heading not for the usual suspects – Almodóvar, Kaurismäki, the Dardennes, Nanni Moretti, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Paolo Sorrentino etc – picked out in my magazine editorial last month (a line-up from which von Trier may have to be dropped in future), but to the relative newcomer Michel Hazanavicius for the brilliant silent-era recreation romantic comedy The Artist. Harvey Weinstein is thought to sniff Oscar potential here, and he and De Niro are old friends… But there we enter the realms of unwarranted speculation, and I’m sure that propriety and taste will rule in this matter. As it happens I think The Artist would be as worthy a winner as many another. For me it’s been a competition mostly about the old stagers showing their chops are still in fine working order, but Hazanavicius is a valuable addition to the line-up.

And besides we still have some treats to come. Nicholas Winding Refn’s The Road screens tonight, Sorrentino’s This Must Be the Place and Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia tomorrow, and there’s more to follow that sadly I will miss since I return to London Saturday morning. Bon chance to all.

Cannes auteurs AOC?

Kirsten Dunst in Lars von Trier’s Melancholia

Jonathan Romney, 18 May

There’s one topic that’s on everyone’s lips in Cannes this year, but it isn’t a film. It’s the fact that for the first time, people entering screenings in the Palais are having all food and drink removed from their bags, even bottles of water. The idea of getting through a whole competition without a quart of Evian at your side is cruel and unusual indeed, and although this year’s programme doesn’t feature much, if anything, over the two-hour mark, I can remember some years when the running times were so exhausting that if the festival organisers had tried to pull this stunt, either there would have been riots or they would have needed ambulances stationed on the Croisette.

Fortunately this year’s competition has been fairly light and pretty refreshing in itself. Not that there was much to refresh cinema itself. What you really hope to find in Cannes competition is something that will rewrite the rules of cinema, or at least show you a few shapes that you’ve never seen before. This year there was very little of that. At the time of writing the only films that have offered genuine innovation, however contentious, were Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life and Lars von Trier’s Melancholia (Denmark/Sweden/France/Germany), and not everyone was enthused by the cosmological pretensions of either.

The von Trier is certainly intensely strange, though – a story about the end of the world that begins with a ‘prelude’ comprising the director’s most dream-like images to date (a dying horse, Kirsten Dunst as Ophelia, a Brueghel painting in flames), then offers a Festen-like comedy of manners set at a wedding party, before concluding with a final-shot apocalypse that was disconcertingly MTV in style, yet eerily touching too.

But at the end of a week, it’s very striking how many of the best films have come from directors doing what they do best – and altogether what you expect them to do best – for the umpteenth time. In competition, there were superb films by the Dardennes (The Kid with a Bike) and Aki Kaurismäki (Le Havre), and in Un Certain Regard a typically rigorous Bruno Dumont (Hors Satan) and an at least partial return to form by Robert Guédiguian (The Snows of Kilimanjaro, France). Each of these films could be justly be described as a quintessential work of their respective directors. Now there’s much to be said for filmmakers staying true to form – and all these films were intensely satisfying. But a great part of the pleasure they offered was quite simply the recognition factor, which allows you to say either, “they haven’t lost it,” or “they’ve got it back”.

Samuel Beckett and Eric Rohmer, in their respective fields, are perennial examples of names invoked in defence of artists who stay true to form. But a prevalence of such filmmakers can weigh Cannes down with the reassuring pleasure of the familiar – and offer a warm hug to critics, especially France’s hardcore auteurists, who love to see the masters doing what they do. Curiously, in Woody Allen’s opening film Midnight in Paris, one of the artists held up as an icon of 1920s white-heat creativity was Luis Buñuel, who rarely did the same thing more than twice, and for whom shape-shifting was as much part of the pleasure of creation as it clearly is for the erratic but always provocative von Trier. Another name from 1920s Paris that Woody Allen could have had his hero meet was Stravinsky, another great shape-shifter. We don’t expect a Rite of Spring in Cannes every year, but von Trier is the only Igor in this year’s competition so far.

Bemusement

Nick James, 18 May

It happens every year: at least one film from France is in competition that the domestic audience seems to adore but which leaves us foreign journalists, almost without exception, utterly nonplussed as to why it was selected.

This year’s puzzle is Pater (France), the latest relaxed, personal, made-at-home film from the usually estimable Alain Cavalier. The director is best known for movingly personal lo-fi work of immense intelligence – for instance Irene, his tribute to his late wife, a moving poetic search for fragments of memory typical of his inventiveness which screened here in Un Certain Regard two years ago.

But what are we to make of Pater? It’s made up from a series of conversations between Cavalier and actor Vincent Lindon in which the director proposes that he is the President of France standing for re-election and that Lindon is the Prime Minister who wants his job. Lindon grabs the attention at first by insisting that the first thing he will do is slash the pay of top bosses.

Laudable stuff, you might think, but in its ‘let’s pretend’ self-reflexive mode the film soon degenerates into mid-scene giggling, and a lot of preening about appearance that’s probably aimed at Sarkozy but isn’t funny (and the cosmetic-surgical removal of Cavalier’s dewlap seems real). Pater is no doubt littered with French political in-jokes, but there could hardly be a more parochial exercise in insider filmmaking. So why put it in the Competition?

Nappy days are here again

Nick Roddick, 18 May

Like Resnais’s Smoking/No Smoking, there are, if not infinite, then certainly a very large number of possibilities at Cannes, depending on which path you take. We all start off at the same point – the opening film (Woody Allen this year as in so many others) – then spiral off into serendipity before returning, exhausted, to our point of departure, aka L’Aéroport de Nice. Which is a roundabout way of saying that there is no such thing as the typical Cannes experience: we all see different films, spot different themes.

At times you can feel fate ganging up on you: on three consecutive days I’ve watched movies featuring incontinence and men (only one of them elderly) having their nappies changed, not to mention two characters taking on-screen craps.

In Alejandro Landes’s Colombian fact-based drama Porfirio (Colombia/ Spain/Uruguay/Argentina/France, pictured at top), about a man paralysed after being shot by a policeman and waiting in vain for his compensation money, the central character’s bathing and diapering are treated with some delicacy, forming part of a daily routine against which he finally rebels.

In Andreas Dresen’s Halt auf freier Strecke (Stopped on Track, Germany), the central character slowly succumbs to a brain tumour and Alzheimer’s. Dresen’s background in documentary, coupled with a brilliant central performance by Milan Peschel, make the film a small masterpiece of humanism – but one for which, as with the director’s previous Wolke 9, it will be very hard to find an audience.

As for the third diaper scene (I’m told I missed a fourth in the Icelandic film Volcano), it comes in Urszula Antoniak’s bleakly minimalist story of a self-harming night nurse, Code Blue (Netherlands/Denmark). And that’s quite enough about that one.

Such details apart, the most striking thing about Cannes this year is the discrepancy in scale. At one end the are movies writ large, not to say overblown: Pirates of the Caribbean IV, for sure, but also Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, so determined to capture the essence of an American childhood and to be the Great American Movie (not to mention a complete History of the Planet) that it eventually sinks beneath its own weight.

Then, at the other end of the scale, there have been, mainly in the Director’s Fortnight, a series of films – the most egregious of which is the Irish/Dutch co-production The Other Side of Sleep, directed by Rebecca Daly – where the image (or perhaps more properly the frame) is the prime signifier. Not character, not plot, not theme, but a series of beautifully composed pictures in which (sometimes) something happens or across which someone passes. Most bear the print of the Cinéfondation, in which Cannes recreates itself in its own image. From the nappy, in other words, to the navel.

Early morning medicine

Nick James, 17 May

Cannes is a bubble which tries to exclude the outside world or indeed one’s personal life, but sometimes reality breaks in. In the last 24 hours I’ve learned of sad family news that I won’t burden you with and I have been with a friend experiencing symptoms of anaphylactic shock. The French ambulance came quickly and my friend is okay. So relax. I mention these things here only to get you to imagine how real events may impact on you if, as has been the case at many a Cannes, you’re watching a lot of grim surveys of human dysfunction.

Happily this year hasn’t been like that. Exceptionally, for instance, there have been two 8.30am Competition screenings that have had the critics applauding with joy and a sense of relief and, amazing to relate, both films are comedies.

On Sunday morning we thrilled to the glorious pastiche of silent-era Hollywood that is The Artist (France, pictured above), written and directed by OSS 117‘s Michel Hazanavicius. The film is A Star is Born meets a sound-free Singin’ in the Rain: a fan’s chance meeting with a Douglas Fairbanks-type hambone swashbuckler with a winsome pet dog sees her become an early talkie star and him a washed-up relic.

This morning that little ray of sunshine known as Aki Kaurismäki denied his long heritage of describing his own films as catastrophes to give us Le Havre (Finland/France/Germany), a sweet romantic comedy about veteran bohemian types giving aid and succour to an African boy trying to make his way to London. There’s nothing like a few good one-liners to lift the mood of everyone at the tired mid-stage of this festival (I loved it when a doctor tells Matti Outinen, playing the cancer-besieged wife of the shoeshining hero, “Miracles do happen” and she replies, “Not in my neighbourhood”) – especially when reality threatens to bite.

Hallelujah, I’m a cineaste

Geoff Andrew, 17 May

Nick James and I have both already commented on the privileged place afforded to sex and sexuality at this year’s festival; Nick on women filmmakers having their say, myself on intergenerational intercourse within the family. (Today’s contribution on that score is the South African film Beauty, in which a macho married timber merchant, who now and then indulges in secret all-male orgies, faces a dilemma when he gets the hots for his young nephew.) So it’s perhaps only fitting that another increasingly visible concern is religion. First up was Nanni Moretti’s account of doubt at the very top of the Vatican, Habemos Papam; next Joseph Cedar’s Footnote (Hearat Shulayim, Israel), a Talmudic tale of temptation and sacrifice. But the actual religious content in these films was fairly minor compared to the double-whammy that hit us on Monday morning.

Terrence Malick – he of the Heidegger tendencies – has always displayed an interest in “all things shining” – to quote the last line of The Thin Red Line – not to mention a fascination with the workings of the universe (hence all those ‘hows’ and ‘whys’ that litter his voiceovers). But his eagerly awaited The Tree of Life (pictured above) left many wondering whether the famously reclusive auteur has ‘found God’. It could simply be a matter of his film reflecting rather than endorsing the beliefs of the 50s Texan family at its centre; still, with its awestruck evocation of the history of the cosmos accompanied by Christian masses and oratorios, and a coda that’s nothing less than a cinematic prayer, the tone undoubtedly feels more religious than philosophical.

Atheists may find this development problematic, but at least Malick is coherent, whereas Bruno Dumont, whose Hors Satan (Outside Satan) is somewhat akin to his earlier L’Humanité, seems to be arguing that the devil himself is stalking the pastures, marshes and dunes of Pas de Calais – though so given to obscure allegory is this curdled reworking of Bressonian aesthetics that it’s impossible to fathom who’s the saint, who Satan’s agent. Hokum it may be, but at least it’s diabolical hokum.

Will this spiritual strain endure into the second half of the festival? Who knows?… as a Malick character might whisper. But even Aki Kaurismäki – famous for dealing with serious issues on a modest, determinedly human scale – includes a single seconds-long scene of prayer in his lovely Le Havre – though whether a subsequent miracle is actually the result of that act is wisely left by the Finn gloriously up in the air.

Happiness is a cinéma verité classic

Agnieszka Gratza, 17 May

A few days into the Cannes Film Festival, it dawns on me that if I see yet another feature delving into the lives of prostitutes, paedophiles, and (mass) murderers I’ll lose the will to live. No matter how new the take on each of these tried and tested themes – and films such as Julia Leigh’s Sleeping Beauty, Hagar Ben Asher’s The Slut and Rebecca Daly’s The Other Side of Sleep, for all their shortcomings, certainly have arresting premises – I cannot help but feel growing crime-and-misdemeanour fatigue.

Argos Films’ digital restoration of Chronique d’un été (Chronicle of a Summer), a landmark in documentary filmmaking shown as part of Cannes Classics, proves the perfect antidote. In a series of interviews filmed during the summer of 1960, at the height of the Algerian War, anthropologist Jean Rouch and sociologist Edgar Morin asked for the most part ordinary, working-class people whether they considered themselves happy. (“Almost”, a woman replies in one of many disarming and increasingly revealing answers to this question.) Agnès Varda, whose presence at the screening was acknowledged by a round of applause, turned to the same subject in her stunning colour-drenched 1965 feature Le Bonheur.

What made Chronique d’un été groundbreaking for generations of filmmakers, starting with the French New Wave, is not so much the enduring relevance of the subject as its experimental approach to documentary-making, from the then-revolutionary use of hand-held cameras and portable sound-sync equipment to the consciously self-reflexive structure that sees the directors film participants’ responses to the screening of the rest of the documentary. Rouche and Morin coined the term cinéma verité to describe their working method, aimed at eliciting truthful responses from their subjects. If documentary features such as this one still strike a chord with viewers today, 50 years on, it’s surely a sign that a film’s ability to provoke rests on more than its shock-value.

Sexual relations: Oedipus and Elektra cruise the Croisette

Geoff Andrew, 16 May

Spoiler alert: this blog entry hints at an important plot twist

Halfway through a festival that’s so far notable more for a generally impressive overall consistency rather than for any major highlights, it’s still difficult to discern any particularly prevalent thematic content. That, of course, is as much to do with the selectors’ interests as with the filmmaking community; still, it’s fair to say the economic crisis, the widespread shift to the Right, war and global warming aren’t leaving much of a mark, at least as far as the official selection is concerned. There seems, however, to be an underlying anxiety lurking beneath the surface of many of the movies on view.

Let’s start, a little obviously, with a film that screened in the first couple of days: Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin (pictured). Discussion of this movie has rightly tended to focus either on the question of the depth of maternal feeling in the character played by Tilda Swinton, or on the Damien-like horror attributes of her malicious offspring. But let’s not forget their problem may be Oedipal; though the son seems to get on far better with dad than with mum, it’s clear there’s something sexual going on towards the latter, and after all, dad does end up in less than the best of health.

But concern about intergenerational sexual activity in the family has also been turning up all in the most unlikely movies. You’d expect to find it in Polisse, a film about the Parisian police’s Child Protection Unit investigating countless cases of abuse, and it’s probably not so surprising that it’d at least be something to bear in mind while watching Michael, the Austrian (but of course!) study of a single man keeping a young boy imprisoned in his cellar. But hints of desire, hatred and jealousy towards real or surrogate parents can be found all over the place – quite literally – from down under (Australia’s Sleeping Beauty) to Scandinavia (Denmark’s Out of Bounds, aka Labrador), while Belgium gets in on the act with the Dardennes’ The Kid with a Bike.

These erotic urges reach across not only geographies but also religions. In Nanni Moretti’s Habemus Papam, Michel Piccoli’s Holy Father seems somewhat devoted to the memory of his mother (or so his shrink suggests), while Joseph Cedar’s Footnote focuses on the hardcore rivalry between a father and son who are both professors of Talmudic literature.

Most recently, there’s been Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, much of which deals with the near-murderous hatred felt for his father by a Texan teenager of the 50s; and even though the film displays an unprecedented Christian bent, Malick still finds space for scenes of the boy chasing his young mother with a lizard and watching her adoringly as she gets soaked by a lawn sprinkler. That said, this prayer of a film goes only so far: there’s one Father whom Malick doesn’t seem remotely interested in killing off…

Terrence Malick: to bury or praise?

Nick James, 16 May

It’s always clear at Cannes which is the most important screening. Feeling the mass anticipation of a chock-full Grand Palais at 8.30am this morning it was obvious that Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life was the one. You knew too that some people had already decided they would completely hate it and some completely love it before they even saw it. For them Malick can either do no wrong or do no right.

Cannes’ atmosphere and the need for immediate reporting have distorted many a film’s reception, but the pro- and anti-Malick camps seem particularly clear in their opposition. You can get caught up in all that excitement despite yourself. I thought I smelled a turkey myself before I came here.

I was happily wrong but I’m not going to go into my full view of the film here because a) I went almost immediately into another theatre to see Bruno Dumont’s Outside Satan – another gobsmacker in its way, b) I’m at neither extreme and c) I’m not quite sure what I think yet. Let others have the first bites, I’d rather let it sink in first. But I am certain that those immediate opinions you read today will reveal as much about the prejudices as well as the advocacies of some reviewers as about the film itself.

Flatliners: affectless sex

Nick James, 15 May

Women filmmakers set the tone for the opening days this year on the Croisette and their main concerns have been sex and/or the absence of ‘affect’. It is, of course, coincidence as well as concerted programming that brings Julia Leigh’s Sleeping Beauty (Australia, pictured above), Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin (UK), Maïwenn’s Polisse (France) and Hagar Ben Asher’s The Slut (Hanotenet, Israel/Germany) together in the same place and time, but the connections between them are multiple.

I’m part of a jury considering The Slut, so I can only describe it: actress Ben Asher plays a woman raising two girl children in a rural community who has sexual relationships with many locals, but when a handsome former neighbour returns to his mother’s house her lifestyle comes under pressure.

Sleeping Beauty (pictured) tracks an even more casually promiscuous, mostly emotionless girl who starts working for a high-class brothel where she’s put to sleep so elderly gentlemen may do with her what they will bar penetrate her.

Maiwenn’s Polisse lets a bunch of high-quality French actors overplay Child Protection Unit cops who advertise how immune they are to the consequences of paedophilia, even though they witness them every day; really, of course, they’re chewed up by it.

Ramsay’s powerful vision is slightly to one side in that it’s not directly about sex (though its use of archery is Freudian in the extreme), but rather about the power play between a monstrously brilliant son and his mortified mother. Kevin’s lack of affect matches Lucy’s in Sleeping Beauty, that of the paedos in Polisse, and the rather pragmatic attitude to sex evinced in The Slut. I’m told one can add the lead character in the Irish film The Other Side of Sleep by Rebecca Daly to the list though I haven’t seen it. The Slut also has its unforeseen paedophile angle.

So why are women insistently describing worlds in which men are often potential paedophiles and sex is just a matter of barter? Obvious answers present themselves, but this Cannes feels like it’s full of films preparing us for a more brutally determinist future and women in particular, it would seem, are preparing for the worst – unless, of course, you think it was ever thus.

See also

Everywhere girls?: Sophie Mayer sizes up the female perspectives in the 2009 London Film Festival (October 2009)

The Woodsman reviewed by Philip Kemp (February 2005)

Sadean women: Geoffrey Macnab on Catherine Breillat’s Anatomy of Hell (December 2004)

Innocence reviewed by Jonathan Romney (November 2004)

Sisters, sex and sitcom: Ginette Vincendeau on Catherine Breillat’s À ma soeur! (December 2001)

Ratcatcher reviewed by Charlotte O’Sullivan (November 1999)

The edge of the razor: Leslie Felperin and Linda Ruth Williams on Catherine Breillat’s Romance (October 1999)

Soul survivor: Kate Pullinger on Jane Campion’s Holy Smoke (October 1999)