Festivals

Cannes Film Festival 2012:

The Sight & Sound blog

A history of violence: After Lucia

Demetrios Matheou on this year’s Un Certain Regard winner, a powerful study of grief and abuse

Web exclusive, 28 May 2012

Mexican film of the festival

Mexico’s Carlos Reygadas may have picked up this year’s Best Director prize for his – in my and many people’s view – mannered and exasperating head-scratcher Post Tenebras Lux, but it’s fair to say a younger compatriot has made a much more significant mark on the festival. Michel Franco’s Después de Lucia (After Lucia), which won top prize in the Un Certain Regard sidebar, has the forthright power that we used to associate with Reygadas.

A few months after the death of his wife, Roberto and his teenage daughter Alejandra relocate from Puerto Vallarta, on the Pacific coast, to Mexico City. He’s coping less well with his grief than the girl, who gives a masterclass in how to make friends and settle into her new school. But then quite unexpectedly a lapse in judgement turns her into its number-one pariah.

As a film about bullying this is almost impossible to watch – I was literally doubled up in distress, so increasingly extreme are the humiliations and abuses inflicted upon Alejandra. But rather than exploiting his scenario for cheap thrills, writer-director Franco has something serious to say about a phenomenon that’s been much in the news in his country; outside the school, Roberto himself proves to be an index of the pervasive casual violence and day-to-day lack of anger management that can only inform the behaviour of impressionable kids.

Most saddening is the lack of conversation between a father and a daughter who clearly love each other. The suggestion is that Alejandra is protecting her grief-stricken father from further distress, a selfless yet foolish gesture that ultimately benefits neither.

Franco has a rigour in the way he goes about his business, a way of developing tension and horror through seemingly banal situations that reminds me of Gerardo Naranjo’s work in Miss Bala. This film opens and closes with two sequences involving the bear-like Roberto: in the first he collects the newly-repaired car in which his wife died, driving it for what seems like an eternity while we wait, on edge, programmed for the worst; in the second he’s at the wheel of a motorboat at sea, riding towards the camera, threatening to express his parental passions in a way that is at once unthinkable and worryingly thrilling. Each is a piece de resistance from a director who really knows how to hold his nerve.

The Un Certain Regard jury was presided over by Tim Roth. It’s hardly surprising that the director of The War Zone, itself a harrowing depicting of child abuse (albeit from another quarter), would appreciate Franco’s film.

This is the Mexican’s second appearance in Cannes; his second film, the kidnap drama Daniel & Ana, screened in the Directors’ Fortnight strand in 2009. It’s only a matter of time before he’s in Competition. In the meantime, hopefully this prize will entice someone to distribute After Lucia in the UK.

Muddy waters run deep

Geoff Andrew sees Take Shelter director Jeff Nichols close out this year’s Competition with an impressive Southern river adventure that owes a debt to Mark Twain

Web exclusive, 26 May 2012

Film of the day

In what was seen by some as a slightly disappointing edition of Cannes, populated by plenty of decent and interesting films but boasting fewer than usual (if any) truly great ones, Jeff Nichols’ Mud, the final film in competition, came as a welcome last-minute surprise. Admittedly, its final 20 minutes fell into generic contrivance and cliché – however early you plant a poisonous snake in a movie, everyone knows that by its end someone, somehow, is going to get bitten – but for the most part Nichols’ follow-up to Take Shelter feels pleasingly fresh and for-real.

Set on and around the Mississippi in Arkansas, it centres on two 14-year-olds, Ellis and Neckbone, who take refuge from their dysfunctional home lives by messing about on the river where their families own houseboats. On a nearby deserted island they encounter Mud (Matthew McConaughey), an initially sinister but soon perfectly friendly type who they soon discover is wanted for killing a man; Ellis, however, himself half-besotted by a slightly older local girl, is more than happy to help Mud out when he’s reassured that the latter only committed the crime out of a desire to protect Juniper (Reese Witherspoon), the girl he’s loved since childhood. So the boys make it their business to reunite the fugitive with Juniper, notwithstanding the fact that he’s being sought not only by the cops but by a team of thugs hired by the dead man’s daddy (a welcome rare Joe Don Baker cameo).

What makes Nichols’ film so satisfying, at least until the melodrama of the final act, is the deftness of the characterisations and the constant sense that things are probably considerably more complex than they’re perceived by the impressively practical but still inexperienced boys. Though the movie feels authentic as a portrait of the contemporary South, it’s also reminiscent of the world of Mark Twain; indeed, Nichols apparently had Tye Sheridan and Jacob Lofland, the young actors who play Ellis and Neckbone, read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn during production.

And it’s those echoes that help to render convincing and even quite magical the potentially implausible story of the boys helping out their desperado friend, no matter the dangers involved. The performances, too, are strong – most of them by comparative unknowns, with Sam Shepard and (briefly) Michael Shannon the most familiar – as are Adam Stone’s ’Scope renditions of the wide river and flat landscapes. A shame, then, that the compulsion to go for a thriller climax and tidy up loose ends turns a good, intelligent drama into something more conventional and artificial; after all, ending a movie with a father and son reassuring one another of their mutual love went out of fashion years ago.

Slow war cinema and Bollysploitation

Jonathan Romney hails the Tolstoy-esque simplicity of Sergei Loznitsa’s possibly bleak, certainly slow In the Fog – and the meta-Troma invention of Ashim Ahluwalia’s Miss Lovely

Web exclusive, 25 May 2012

Film of the day

Spoiler alert: this post gives away plot twists

One Tweeter in Cannes complained today about critics automatically using the words ‘slow’ and ‘bleak’ as terms of approval. So I might want to be careful what I say about In the Fog, by Belarusian-born director Sergei Loznitsa. This was the Competition film I was perhaps most keen to see, given that I loved Loznitsa’s underrated My Joy, which played here in 2010 (and strangely remains undistributed in the UK).

In the Fog is a simpler, substantially less strange film than My Joy, which wove together several seemingly unrelated anecdotes into a panorama of the chaos and violence that Loznitsa sees as the historical base note in Russian society. The new film is a war drama, based on a novel by Vasil Bykov, set on the western edges of the USSR in 1942, under German occupation.

The film begins with an extraordinary long-take tableau that culminates in the hangings of three men, and then follows three different men and shows how the causes and effects of those hangings in their lives. The three are partisans Burov (Vlad Abashin) and Voitik (Sergei Kolesov) and Sushenya, a disgraced railway worker (Vladimir Svirski), whom the partisans are going to kill on suspicion of having betrayed the dead men.

As the main drama develops, Loznitsa gives us extended flashback interludes, rather like self-contained short stories, one for each of the three characters. The bitter irony at the centre of the film is that it is Sushenya, who has taken part in an act of anti-German sabotage and then refused to betray his comrades, who is hanged. In an act of exquisite cruelty, German commandant Grossmeier (Vlad Ivanov, whom you may recognise as ‘Mr Bebe’ from Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days) sets him free, knowing he’ll become a pariah, as well as bait for the partisans he wants to capture.

Possibly the slowest and most contemplative war film ever made, In the Fog is a delicately complex work of shifting perspectives, and like My Joy, a contemplation on narrative and the act of storytelling. The wonderfully bitter payoff of the Sushenya flashback is that he has at last stated the case for his defence – even if it’s not one that can possibly save him – but it’s only at the end that he realises he’s told it to a dead man.

The film’s consideration on justice, moral integrity and martyrdom unfolds in a way that’s all the more telling because it’s so simple – and I’ve just had a conversation with someone who regarded the film as mundane. Yet to me, the theme’s development felt lucid in a particularly deep way – it’s the lucidity and depth of Tolstoy’s short stories.

The film is extraordinarily acted, largely in a sotto voce style that expresses the dogged determination and patience of these characters. Actors and landscapes alike could have come out of nineteenth-century Russian paintings; as Sushenya, Svirksi’s looks and stillness make him the embodiment of an age-old Russian archetype – the wise peasant who embraces his fate against all promptings of worldly logic.

Yes, the film is slow – shot by Oleg Mutu, it’s edited with only 72 cuts – and I suppose you might call it bleak, although it shows an enormous faith in human capacities. But I’m not automatically praising it because of those qualities. It’s just among the handful of truly eloquent and moving films here.

Indian independence

A brief word for Miss Lovely in Un Certain Regard. This started off as a shock to the system – an Indian film like I’d never seen, it follows the 1980s misadventures of an aspiring filmmaker struggling at the very arse-end of Bollywood, helping make sex-and-horror exploiters (think of Troma with matronly vamps doing soft porn).

The film is mesmerising for the first hour or so, during which, the echoes of Boogie Nights aside, I found myself thinking of Wong Kar-Wai, Scorsese, Matteo Garrone’s Gomorrah and even Irma Vep. Unfortunately the film then palls somewhat – director Ashim Ahluwalia can’t hold onto a story, or develop characters. But while it’s good it’s very good indeed, and had it been that touch better (and shorter) it could have been a game-changer for Indian cinema.

I’ll be eager to see Ahluwalia’s second film. I know in reality that often means I’d like to see him get a second chance to remake the same film as it should have been. But seriously, I would: he’s a very impressive talent, and given the oppressive conventions of the Indian film industry, he’s clearly an independent spirit and then some.

Cinema-chewing:

Leos Carax’s Holy Motors

Demetrios Matheou wonders at the French former wunderkind’s madly eclectic meta-movie – and, less happily, at a directorial feature debut from actress Sandrine Bonnaire

Web exclusive, 23 May 2012

Film of the day

It’s been 13 years since Leos Carax’s last feature-length film, Pola X. When you wait that long for a one-time enfant terrible to show his face, the anticipation is mixed with anxiety. What if the older man is now, simply, terrible?

Imagine the relief, then, when the gleaming Holy Motors was wheeled out of the garage in Cannes, an ambitious, brilliantly bonkers shot-in-the-arm to the Competition. Carax may now be in his fifties, but he’s still making films like a young man desperate to explore and have fun with the medium. Thank God for a Palme d’Or contender who dares to be different.

A prologue features Carax himself navigating a surrealist dreamscape, at the end of which he looks down upon an auditorium, in which an audience sits impassively as Etienne-Jules Marey’s chronophotographed athletes flicker across a screen. The nod to that early pioneer signals the fact that cinema itself is a subject of the film. At the same time these still figures remind one of Last Year in Marienbad; and like the characters in that film, the protagonist of Holy Motors will be on an endless round of role-playing, in search of an identity.

When we first see him, Monsieur Oscar (Denis Lavant) is a well-to-do businessman, climbing into his stretch limousine and asking his driver (Edith Scob) about his appointments for the day. We imagine a dreary round of business meetings. But then he takes out a lady’s wig. And when the car parks, an old, decrepit woman climbs out and starts to beg on the streets.

Before we’ve had time to take this in, Oscar has changed costume again, into a motion-capture suit, in which he enters a studio and performs a series of energetic stunts, including a sensual clinch with a woman, their fully-clothed writhing transformed into the naked coupling of reptilian monsters.

Oscar is a role-player, then, a master of disguise, performing for invisible cameras and for audiences who we can only imagine are enjoying an exclusive sort of pay-per-view. His other ‘appointments’ include a green-suited, lurching Leprechaun (Lavant reprising the monster from Carax’s contribution to the three-hander Tokyo!) who kidnaps a model (a seductively aloof Eva Mendes) and takes her into his subterranean lair; a killer whose victim is his splitting image; an angry father berating his daughter; a dying old man; and a man who goes home to his family, which happens to be a pair of monkeys.

That simian domesticity evokes Oshima Nagisa’s Max Mon Amour (1986), one of a number of references that will make this a cinephile’s wet dream. But it’s far from a dry exercise – seconds after Scob has donned her mask from Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1960), a fleet of limos start speaking to each other, in a totally unexpected homage to Cars.

It’s a hoot, but also mysterious and moving. Oscar is becoming exhausted by his characters, losing sight of his own identity. “Is it you?” asks Eva (Kylie Minogue), a fellow performer when they meet in the street. “I think so,” is all he can answer. Oscar also reminisces about the days when he could see the camera in front of him, at that moment conveying Carax’s own view as to how technology is damaging his art form.

Minogue has an on-screen charisma singularly lacking in fellow singer Pete Doherty, who has appeared here in Confessions of a Child of the Century. As for Lavant, well, he’s so multi-skilled and chameleon-like that he hardly seems human. Carax says, mischievously, that if the actor had refused the film he would have offered the parts to Lon Chaney or Chaplin. It’s a fitting compliment.

The prodigal step-father

Sandrine Bonnaire’s Maddened by His Absence (J’enrage de son absence) is itself a tad maddening, an initially interesting and sober drama that slowly goes off the rails. William Hurt and Alexandra Lamy play a former couple who reunite eight years after the death of their young son, the pain of which led to their separation. She’s moved on, with a new partner and son; he has no one. But when he sees her boy, he becomes obsessed with the idea that they can have the father-son relationship he was denied before.

As a consideration of the variations of grief, this has some value; and Hurt conveys his character’s desolation with a rare intensity. But he can’t do anything about the preposterous plot development. Incidentally, Bonnaire shares a daughter with her leading man, and ex-lover; it’s grand to see them working together, but it’s not quite the reunion it should have been.

Still dreaming wild things:

Bernard Bertolucci goes underground

Geoff Andrew sees the veteran master make his long-awaited return with a modest, subterranean two-hander

Web exclusive, 23 May 2012

Film of the day

There was a gap of nine years between Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers and Me and You, due mainly to the fact that the back problems which have long plagued the director eventually meant that he became a wheelchair-user. Having come to accept his diminished mobility, he found a subject – in Niccolò Ammaniti’s novel Io e Te – that suited his purposes: the meeting of teenage boy, hiding out in the basement of the apartment block where he lives with his parents, with the 25-year-old half-sister he barely knew existed.

It’s more or less a two-hander, then, though Bertolucci opens the movie with Lorenzo (Malcolm McDowell-lookalike Jacopo Olmo) reluctantly undergoing a session with a psychiatrist (himself also, as it happens, in a wheelchair). Judging by the boy’s tantrum when he insists his mother let him out of the car at some distance from the bus where his schoolmates are gathered to go on a skiing trip, it’s clear that Lorenzo has his problems – though the real reason he wants to be dropped off away from the kids is that he’s no intention of joining them at all; he’d rather relax in secret in the cellar, alone with his books, music and ants for a week.

All that changes when Olivia – a junkie going into cold turkey – turns up out of the blue, looking for long-lost belongings. Inevitably, sharing both the cramped space and revelations about their father’s familial arrangements makes for conflict… but also, in time, for mutual support and even intimacy. As alert (and largely sympathetic) as ever to the confusions, curiosity, vitality and delusions of youth, Bertolucci makes the most of the pair’s few days together; since Lorenzo had already embarrassed his mother with some transparently Freudian questions, it’s hardly surprising that there’s a sexual element in the siblings’ responses to one another. (Fascinatingly, when we first glimpse Olivia, it’s a little difficult to tell if this hieratically handsome creature is a woman or a transvestite.)

Bertolucci explores the strange, subterranean realm of these enfants terribles with characteristic visual flair: décor, costumes, colour and camera movements combine to create a faintly feverish atmosphere. Interestingly, however, the mise en scène is not especially baroque; though expressive, it’s carefully controlled so that the style suits the parameters of the story.

A modest film, then, but enjoyably so: the two lead turns are spot-on, and the use of a reworded Italian version of ‘Space Oddity’ (but still sung by Bowie) deftly captures not only the dynamics of the pair’s brief encounter but the aching, fragile hopes of a boy in need of a friend.

Last works and wakes:

Alain Resnais in the underworld

You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet

Amy Taubin hopes death succeeds patriarchy as the flavour of this year’s festival

Web exclusive, 22 May 2012

Death is inescapable at Cannes this year. In the best film so far, Michael Haneke’s Amour, two legendary French actors, Emmanuelle Riva and Jean-Louis Trintignant, play respectively a dying woman and the husband who is her caregiver 24/7. But no one watching this unsparing and compassionate film could doubt that the actors, with over 50 years of their careers behind them, were rehearsing, before our eyes, the way that death might come to them as well as to their characters.

Film of the day

The 90-year-old Alain Resnais does it differently, couching death as the essential element of a great romance as well as of an absurdist comedy. Resnais’ previous film, the surrealist manifesto Wild Grass, is one of his greatest; You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet is slighter by comparison, but still has many ravishing moments that are at once poignant and exhilarating. It was rumoured to be Resnais’ final film, but happily he is already embarked on another. Nevertheless, the governing concept of YASNY is that of the posthumous work, a concept that is then overturned, and perhaps overturned again.

A group of actors have been summoned to what they believe is the wake for the writer of Eurydice, a modern adaptation of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, in which they all performed. They are asked to view an experimental film version of the play, but, being actors, they are incapable of sitting still and watching a movie; instead they are irresistibly drawn into recreating the characters they played when they were much younger. Film space and theatrical space merge and separate and merge again until who knows which is which.

The version of Eurydice that Resnais employs is a condensed version of the 1942 play by Jean Anouilh. In the press booklet for the film, Resnais recounts seeing the original production and afterwards riding around Paris on his bicycle in an extremely emotional state.

What he doesn’t mention in his notes or dramatise in You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet is that the play has a subtext that is specific to the Nazi occupation of France. It’s a play which was virtually written in code. Anouilh’s Eurydice isn’t simply the damaged woman who would become the object of desire in the noir films that Resnais loves; the specific sin for which she can’t forgive herself is that of sleeping with the enemy, albeit she did what she did to save people she loved. And while the Occupation may be nearly as far in the past as ancient Greece, the play seems a bit lightweight without that frame of reference.

Nevertheless, the film is more than the play. Most of all, it gifts us with its actors, the most memorable of whom are Mathieu Amalric and Michel Piccoli.

Patriarchy from the east to the west

While not exactly a cause celebrate for international feminism, the absence of female directors from the Competition slate has been angrily noted on many blogs and in many press conferences. Of course, the problem doesn’t start with festival programmers, here in Cannes or elsewhere. It’s the refusal of most producers and moneybags to back female-directed projects that results in programmers having very few to choose from.

There are, nevertheless, a handful of movies directed by women in various sidebars. By the end of the festival we’ll know if Sandrine Bonnaire’s J’Enrage de Son Absence and Alice Winocour’s Augustine (both in Critics’ Week) or Noemie Lvovsky’s Camille Redouble, Yulene Olaoizola’s Fogo and Catherine Corsini’s Trois Mondes (all in Directors’ Fortnight) would have shown to better advantage in the main Competition.

On the other hand, we’ve already seen two Competition films directed by men that depict patriarchal institutions as the enemy of liberty, even after reactionary regimes have been overthrown. The underrated Egyptian film, Yousry Nasrallah’s After the Battle, makes it infuriating clear that even though they were on the front lines, women won next to nothing in the revolution at Tahir Square.

Nasrallah is not entirely successful in depicting a complex political landscape (his male characters tend toward caricature) but his female protagonist, an economically privileged young woman turned workers’-rights organiser and something of an animal activist, makes the film both satisfying – if the feminist struggle is something you care about – and uncommon. And the final sequence is heartbreaking.

Cristian Mungui, who won the Palme d’Or in 2007 for his unsparing 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days, aka ‘the Romanian abortion movie’, is back at Cannes with the harrowing, bleak-humoured Beyond the Hills. As in 4 Months, he places two young women at the centre of the narrative. Best friends and almost certainly lovers when they lived in an orphanage, they separated when they came of age, one going to Germany to look for work, the other winding up in a tiny snowbound Christian Orthodox community. This is all backstory, deftly communicated shortly after the film begins.

The young woman who went to Germany returns to Romania to find that her friend has drunk the religious Kool-Aid. When she attempts to rescue her, the priest and his corps of brainwashed novices deem her possessed by the devil. An exorcism ensues and ends badly. An atheist’s version of Dreyer’s Day of Wrath, Beyond the Hills is a film of great formal rigour and a furious indictment of religion as an instrument of patriarchal oppression.

Love by Michael Haneke

Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva in Amour

Nick James checks his notes: the festival’s most tender as well as telling film so far comes from the Austrian disciplinarian

Web exclusive, 21 May 2012

Film of the day

Michael Haneke’s Amour (Love) is the par excellence film so far at this festival, a chamber piece that’s as meticulously controlled in tone as you’d expect of the Austrian master. With the exception of one piano-performance scene at the beginning, the film never leaves the apartment of married couple Georges and Anne, elderly former music teachers. The only other people we meet are visitors, including their musician daughter Eva (Isabelle Huppert), her English husband Geoff (William Shimell) and the pianist Alexandre Tharaud (playing himself as someone they taught).

As the decisive, forthright Georges, Jean-Louis Trintignant has a role to match that in Kieslowski’s Three Colours Red, his calm, insistent voice still resonant with maximum authority. Emmanuelle Riva is Anne, all elegance and insight. One morning, not long after a Schubert concert by Alexandre that we’ve seen them attend, they are in the kitchen when Georges finds that Anne has ‘switched off’ – she’s sitting there but he can’t get a response. A few minutes later she’s herself again. With no maundering and the minimum of hand-wringing Georges sets about dealing with Anne’s failing struggle with her fading powers after a double stroke.

Scene after scene is an exquisite masterclass of astonishing acting from both – though Riva’s performance of her efforts to talk is beyond anything I’ve seen an actor do for a while – and telling detail from Haneke (though he spares the dignity of his leads). For once, the only cruelty present in a Haneke film is the ultimate cruelty of life’s end. I’ve spoken to several people here who’ve had to attend to the decline of their parents, and every one attests to the tender accuracy of this uncharacteristically emotional film.

The actors have it

The fact that the most impressive film here is such an actor-centric piece fits the programme so far. I’ve never seen a Competition so full of great performances, too often in films that themselves don’t quite make the mark. Marion Cotillard and Matthias Schoenaerts (Rust and Bone), Aniello Arena (Reality), Margarethe Tiesel (Paradise: Love) and Cosima Stratan (Beyond the Hills) have all amazed. The same is true for Mads Mikkelsen in Thomas Vinterberg’s The Hunt, a tremendously gripping melodrama about a man wrongly accused (as far as we can see in the film) of paedophilia.

It’s the mid-point, after a constant rain-stormy weekend. I’ve seen 23 films, which seems enough of a sample to draw some tendencies. If Cannes was at its end now I’d have to say for much of the time it was a pretty damp affair all round. But of course good weather and strong films may yet return. I’m all too aware that the complaining of veterans like myself is always at its height mid-festival.

But as a final note I’d like to mention only in passing that Kiarostami’s ambiguous Like Someone in Love – a brief encounter between a young girl who may be a prostitute, an old man who may be her client and the insanely jealous young man who may be her boyfriend – seemed rather slight on a single viewing for a viewer who was soaked to the skin.

Mortal mischief:

Raul Ruíz’s La Noche de Enfrente

Jonathan Romney on the late Chilean master’s fond farewell to a life of artistic delinquency

Web exclusive, 21 May 2012

Film of the day

As a follower of the wildly prolific Raúl Ruiz for some 30 years, it seems hard to believe that a time has come when I won’t be looking forward to his latest film of the year, month, even week (as it has sometimes felt). Still, he can’t have bowed out in more stylish fashion than with his Chilean-filmed swansong La Noche de Enfrente (loosely, The Night Before Us), given a special screening in Directors’ Fortnight. Many people regarded his Portuguese epic Mysteries of Lisbon as his valediction, given that it was preoccupied with the idea of wrapping up the narratives and legends of a person’s lifespan (but then, so were many of his films). Lisbon may have been his last major film, his Testament with a capital C, if you like, but La Noche de Enfrente is, as it were, a codicil to the will, and a fond farewell note.

A rather abstract quasi-narrative, in keeping with some of Ruiz’s French films of the 80s, the film is ostensibly about an elderly Chilean, Don Celso, who, on retiring from his office job (in which he seems to have found the secret “of working and relaxing at the same time”), awaits the arrival of the mysterious stranger who will before long kill him. In the meantime, he discusses words and poetry with his teacher Jean Giono (Christian Vadim), who may or may not be the novelist of the same name; and remembers his childhood, in which he philosophised with adults and conversed with his guiding spirits Beethoven and Long John Silver.

The film is very much the proverbial ‘poem in images’, and a truly free-associative one, in vintage Ruiz style. There are some marvellous verbal finds – I love the idea of the passing moments solidified as “marbles of time”, and there are some delightful running gags, like the waiter who keeps turning up to remove a bust of Beethoven as if it were an empty salt cellar. The digital photography is gorgeous, particularly in its use of rose pastels and the bronze look of its seascapes. There are winks at earlier Ruiz films – notably, his adaptations of Giono, Robert Louis Stevenson and Arthur Adamov – and while the musings on death may be in a black-comic mode, they’re remarkably jolly. I especially liked the scene in which the dead hold a séance to contact the living.

All in all, there can’t ever have been a case of a director making such a cheery, mischievous film to contemplate his own mortality (Ruiz, ill with cancer, had already risked death to complete the epic Mysteries). The Directors’ Fortnight send-off was suitably jolly too, with one associate remembering that Ruiz’s idea of teaching film students was to espouse “artistic delinquency”.

Producer François Margolin cheekily paid tribute by saying that he’d tried to contact Ruiz for the occasion, but without luck: “He still doesn’t have a mobile.” But he read out a note that he said the great man had dictated from the afterlife: the producers up there don’t understand digital, but not to worry, he has his Sony up there with him, is busy shooting, and expects to bring the results to Directors’ Fortnight next year. You know what? Don’t be surprised if he does.

Sex on tap:

Ulrich Seidl’s Paradise: Love

The Austrian director’s sex-tourism drama could be his richest film yet, says Pamela Jahn

Web exclusive, 20 May 2012

Film of the day

If a number of the Competition films so far seem to have divided critics down the middle – Matteo Garrone’s Gomorrah follow-up Reality and Jacques Audiard’s Rust and Bone come to mind – then another noteworthy Competition film, coming from ferocious Austrian provocateur Ulrich Seidl (Dog Days), was probably always destined to join them, no matter its low-key premiere on Friday afternoon. Yet if Seidl’s previous feature Import Export (2007) was a rigid, often almost unbearably brutal look at the exploitation of human labour on both sides of what used to be called the Iron Curtain, his new Paradise: Love (the first part of a ‘Paradise’ triptych spanning Faith and Hope) finds him moving into emotionally warmer territory.

A group of chubby, sexually undernourished middle-aged women have found their utopia in a luxury Kenyan hotel complex where they hook up with local beach boys eager to accommodate them for money. First-time visitor and single mother Teresa, who has parked her teenage daughter with her sister for the duration of her trip, initially feels uneasy about the prospect of finding sexual fulfilment with an underage boy, however – until she can no longer resist.

Boasting a pitch-perfect performance by Margarethe Tiesel as Teresa, Seidl’s film is full of mildly absurdist dialogue, contrasting the banal environment of the tourist facility with the brutal and cynical craving for sex on tap. Seidl enjoys pushing Teresa further and further up the emotional creek, but the film is attuned to the moral complexity of the situation, and also surprisingly tender.

Still, it’s fair to say no film here has really yet caught fire. Then again, we’re only a few days into the festival, and my hopes remain high for the second Austrian Competition entry, Michael Haneke’s Love, screening in bracing fashion at 8.30am Sunday morning.

Nuns on the verge of a nervous breakdown:

Cristian Muniu’s Beyond the Hills

Geoff Andrew on the Palme d’Or alumnus’s return to the Competition

Web exclusive, 20 May 2012

Film of the day

Since Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days was only his second feature, having been preceded by the promising but unremarkable Occident, it was hard to tell until now whether his Palme d’Or-winner might have been a flash in the pan. Happily, judging by his third feature, it seems it wasn’t. Though Beyond the Hills lacks the taut dramatic suspense that made its predecessor so riveting, it nevertheless stands as the most consistently satisfying film to have screened in Competition so far.

Inspired by a true story and based on a couple of ‘non-fiction novels’ dealing with the incident and its aftermath, Beyond the Hills chronicles the chain of events that occur when Voichita, now a young nun, receives a visit from Alina, who had been her closest friend in the orphanage they grew up in. Alina, returning from a lonely sojourn in Germany and emphatically not a believer, wants her friend (and, perhaps, former lover?) to give up the monastery and her devotion to God. But Voichita, like all her ‘sisters’, is happy to obey the instructions of the Orthodox (in all senses of the word) priest who tends to the spiritual well-being of the place. And that means putting her duty to God and the Church above all other considerations, including that of human love – and, perhaps, genuine compassion.

It’s Alina’s dependence on Voichita, and the nuns’ and priest’s response to her demands, that drive the eventful, pacy, faintly over-extended narrative of Mungiu’s quietly assured film. As disagreement and negotiation turn to conflict and, finally, an attempt at exorcism, there are perhaps a few too many repetitive instances of the ‘Help! Come see what she’s doing now!’ variety, but at the same time Mungiu exhibits an admirable patience and fair-mindedness in teasing out the situation’s ethical complexities. For all the priest’s talk of sinfulness, no one here is a heroine or a villain; indeed, Mungiu asks (in the press notes and, implicitly, in the film) whether one of the most dangerous manifestations of ‘Evil’ might not be the sin of indifference, and the film pleasingly reflects that non-judgmental refinement of thought.

While there’s an almost tragic inexorability to the events depicted, the film frequently surprises by providing small but telling details and ambiguities. In short, it has both substance and subtlety.

‘No’ for a lighter, nicer Chile

Demetrios Matheou sees Pablo Larraín close out his trilogy about Chile’s years of dictatorship with wit and verve

Web exclusive, 19 May 2012

Film of the day

You might think that a director is playing with fire by calling his film No, especially in Cannes where critics eagerly embrace any opportunity for a smarmy put-down. Pablo Larraín needn’t worry. Applause and cheers for the final instalment of his trilogy about the Chilean dictatorship lasted well after the lights had gone up here, leaving the filmmakers on stage with nothing to do but clap back.

It was well merited, and makes one wonder why this isn’t in Competition. Larraín has serious form, and his film is at once worthy, skilfully made and hugely entertaining – a rare combination that eludes many a po-faced festival entry.

With Tony Manero, Larraín presented a unique perspective of life in the midst of Pinochet’s dictatorship; in Post Mortem he cast back to the regime’s beginning, and the coup itself; now he looks to its unexpected demise. Coinciding with the obviously more upbeat message, he’s made his closest yet to a crowd-pleasing, mainstream movie.

In 1988, Pinochet was forced by the international community to make some show of democratic reform. His sly concession was to call a referendum on whether or not he should remain in power for a further eight years. For the first time, opposition parties were granted air-time to voice their views. But no-one believed it would make a difference. It was felt that Pinochet could win even without cheating, because of what one character in the film calls the “learnt hopelessness” of the people. They simply wouldn’t bother to vote.

Larraín and writer Pedro Peirano (who scripted the fantastic The Maid) tell the tale of how the No campaign defied those predictions. Their central character, played by Latin cinema’s go-to hero Gael García Bernal, is René Saavedra, an amalgam of two of the men most instrumental in the No campaign. He is a terrific creation, a skateboarding ad man who we first meet presenting his advertisement for a fizzy drink called, with brilliant irony, It’s Free. When he wants to get a kiss out of his ex-wife, a radical campaigner, he simply uses the word ‘Allende’.

The genius of René’s No campaign is to take the frivolous and superficial tropes of advertising and apply them to the referendum. Much to the horror of the opposition parties who have engaged him, he doesn’t want to preach about the disappeared, or the fact that millions live in poverty – the country’s misery, he says, “won’t sell”. He wants to talk about “happiness”.

The comedy in Larraín’s earlier films was pitch black. Now, befitting its more upbeat historical moment and the sheer jolliness of the No campaign, it is much broader. In fact, it’s as if the director is applying René’s maxim, “a little lighter, a little nicer”, to himself. Even Alfredo Castro, the sinister star of the previous films and firmly in the Yes camp, gets to let his hair down. At the same time, we’re left with no doubt what’s at stake. People are constantly speaking in whispers and in public spaces; René, his family and colleagues are stalked by men in unmarked cars. Much of the feel good vibe is due to our witnessing a country coming out of the shadows.

In a stylistic masterstroke, Larraín shot his film with a 1983 U-matic video camera, so that there’s virtually no difference between the copious archive footage and the new. It’s a seamless whole, and an enormously satisfying one.

The wrong earlobes: The Imposter

Tom Charity on a smart doc fresh from Toronto’s HotDocs and Sundance – and Bernard Rose revisit Tolstoy in Hollywood

Web exclusive, 19 May 2012

Film of the day

In belated recognition of the rising profile of documentary film on the exhibition circuit, the Cannes market has come up with a freshly-minted ‘Doc Corner’ this year. You could make the case that a fully-fledged official selection would be in order. In the meantime, though, the likes of IDFA and HotDocs fill that void, and The Imposter arrived in the Marché with a headwind of plaudits from the latter, and Sundance before it.

Produced by John Battsek and directed by Bart Layton, The Imposter adopts many of the strategies pioneered by Errol Morris and mainstreamed by James Marsh to relate the strange tale of Frederic Bourdin, a French runaway who came across a ‘missing persons’ leaflet in a shelter in Spain and claimed to be Nicholas Barclay, who had disappeared from San Antonio, Texas, at the age of 13, three years before.

To his dismay, Barclay’s sister, Carey, immediately flew to Spain to bring him home. Amazingly, she embraced him as her sibling, even though the dark-haired, brown-eyed French youth scarcely resembled the blond, blue-eyed Nicholas pictured on the poster. (Frederic dyed his hair, duplicated Nicholas’s tattoos, and hid behind a baseball cap, shades and a scarf.) She also produced family snapshots and helpfully identified the relatives he had forgotten during his traumatic abduction. Within days he was on a plane to Texas with a US passport in his pocket.

Layton has interviewed all the key players here, juxtaposing Bourdin’s perspective with those from Nicholas’s family, his sister, mother and uncles, as well as government officials and a private eye – Charlie Parker – who started digging into the affair in earnest after getting a good look at Frederic’s earlobes. The talking heads are interspersed with dramatic reconstructions and evocative photography of the Texan hinterlands, backed up with choice musical cues (Johnny Cash, David Bowie, Cat Stevens) and even some scratchy home video shot by the Barclays on ‘Nicholas’s’ return.

More than anything it’s Layton’s storytelling acumen that impresses – the movie unfolds like a psychological thriller, and in the second half effects a chilling twist on its own inherent implausibility, as Frederic begins to wonder if he has fooled these people at all. The mystery deepens in a maze of lies, denials, and unproven speculation, and we are left pondering how much of our identity is up for grabs, constructed through the filter of other people’s perceptions, needs and desires.

Before the revolution

A companion piece to his ivansxtc, Bernard Rose’s Two Jacks is a minor but piquant addition to the tradition of Hollywood eulogising its monsters sacres. Rose again turns to Tolstoy for inspiration, this time his story Two Hussars. Los Angeles in the pre-social media days of the early 90s proves an amusing analogue to pre-Revolutionary Russia.

Danny Huston plays Jack Hussar, last of the old-school movie directors, a cigar-chomping legend among those who still care about good movies, even if none of them made a dime. Newly returned from Africa, where his latest project has run out of funds, Jack graciously permits fan/acolyte/would be producer Brad to drive him around LA, clear his debts, and introduce him to his beautiful sister Diana (Sienna Miller). Huston is ideally cast of course, and nails exactly that air of detached, but faintly debauched, authority that artists assume and probably require. His only loyalty is to the money he needs to fulfil his vision – and to whatever beautiful woman crosses his path.

In the neatly turned second half, Danny’s son Jack plays Jack’s son Jack Hussar Jnr, who again crosses path with Brad and Diana just as he embarks on his own Hollywood odyssey. Like ivansxtc Rose shot this digitally (he’s his own cameraman) on the kind of budget Hussar senior would eat for breakfast. It looks pretty crappy, truth to tell, but the writing is crisp and ascorbic, and veteran Richard Portnow is nothing short of satanic as Lorenzo, a studio powerbroker who likes to stake final cut on a hand of Texas Hold ’Em.

Crime and punishment in Kazakhstan

With the festival’s slow start continuing, Geoff Andrew singles out a quietly resonant new riff on Dostoevsky in the festival’s Un Certain Regard sidebar

Web exclusive, 18 May 2012

Film of the day

After A Prophet, you might justifiably have expected Jacques Audiard’s Rust and Bone to have been the most impressive film of the second day of Cannes press screenings. But that particular redemption drama screened to a very mixed reception, and while I was certainly to be found at neither end of the critical spectrum, for me today’s most satisfying movie was undoubtedly Student, by Darezhan Omirbayev.

It’s more than a decade since the Kazakhstani director’s The Road (also in the Un Certain Regard strand) met with a warm reception from the Cannes critics, but the new film shows he hasn’t lost his capacity to combine simplicity of method with subtlety of resonance. Inspired by Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, it’s just as much concerned with redemption as the Audiard movie, but in its own quiet way is rather more persuasive. About an impoverished, lonely and almost catatonically shy philosophy student who commits a fatal robbery and only gradually comes to see the full error of his ways, the film is often reminiscent (in its lighting, colour schemes, low-key acting style and pacing) of Aki Kaurismäki’s version of the same novel, though for the most part without the Finn’s trademark deadpan humour.

Indeed, with its pared-back, taciturn, almost Bressonian directness, Student might even seem like a rather naïve take on the Dostoyevsky theme, were it not for Omirbayev using a couple of scenes of philosophy lectures and some judiciously chosen clips playing on the student’s landlady’s television to add depth to the theme of responsibility and ethics; how are we to regard the student’s actions given the nature/nurture debate and the changes that have overtaken Kazakhstan in recent times? Such considerations are mercifully never hammered home but simply included as part of the film’s overall fabric, as material for us to think about should we wish.

While it would undoubtedly be wrong to make great claims for Omirbayev’s film, it certainly doesn’t outlast its welcome and fulfils its admittedly modest ambitions. That’s surely quite enough to be going on with, and more than could be said for Lou Ye’s Mystery, the somewhat murky tale of marital infidelity and suspicious death that served as the opening film for the Un Certain Regard strand.

Simple versus simple: After the Battle

Yousry Nasrallah’s instantly derided melodrama of Egypt’s 25 January Revolution may simplify, says Nick Roddck – but at least it does so differently…

Web exclusive, 18 May 2012

Film of the day

Given the apparently universal dismissal of Yousry Nasrallah’s After the Battle by my UK colleagues, I take a certain perverse pleasure in making it my film of the day. Not that there’s much competition, since only three films were shown in Cannes on Wednesday (plus a couple more that were semi-secret).

Nasrallah’s film is joyously direct, sometimes to the point of crudeness, but does an interesting job in fusing Egyptian melodrama with a kind of Loachian education-through-conflict approach to the events in Tahrir Square. The story of an improbable love affair between a radical young professional woman and an illiterate horseman conned into taking part in the infamous assault on demonstrators by camel- and horse-mounted thugs, it gains its strength from its determination to undermine the simplistic scenario we have been fed from Cairo. Instead we get an uncomfortable, if unsophisticated, examination of the class implications of the situation in contemporary Egypt, where the paralysis of the tourist economy has left the inhabitants of Nazlet, who relied on taking tourists round the pyramids, destitute and confused.

I don’t usually allow a heart being in the right place to excuse over-simplified characters and contrived confrontations. But After the Battle is such a useful corrective to the romanticisation of the Egyptian revolution that forgiveness is easy. It deserves to be seen more widely.

Fleeting pleasures: Moonrise Kingdom

Day one, and Nick James is in two minds about Wes Anderson’s scout-island fantasia

Web exclusive, 17 May 2012

Film of the day

No contest that the first-day highlight was the gentle massaging Cannes opener, Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom, but then all it had to compete with were two director-profile docs – Robert Weide’s Woody Allen: A Documentary and Laurent Bouzereau’s Roman Polanski: A Film Memoir – and a rather crude and hectoring Egyptian political film in competition, Yousry Nasrallah’s After the Battle.

Cannes does like to ease us all in gently with a crowd-pleaser – typically something like Pixar’s Up – and Moonrise Kingdom makes a winning appeal to the precious joys of the pre-teen imagination circa 1965. This time Anderson’s special discrete world is that of a sparsely inhabited island off the coast of New England, and his eccentrically dysfunctional family is a pair of lawyers played by Bill Murray and Frances McDormand. Among their brood of three sons they also count Kara, a puberty-cusping daughter addicted to her binoculars, who has so much self-awareness that among her more imaginative reading of adventure stories is a book on how to raise a disturbed child. She absconds into the island’s hinterland with Sam, a semi-delinquent orphan boy who’s run away from a scout troop.

I don’t want to pre-empt here the extraordinary layers of excellent detail that makes Anderson’s mise en scène so droll and delicious, nor the excellent use of music by Benjamin Britten, Hank Williams and others – nor indeed the social-problem love story itself – since much of all that is explained in Nick Pinkerton’s interview with Anderson in our current (June) issue of S&S, on sale now. Suffice to say that this is the director’s lightest film yet – lighter even than Fantastic Mr. Fox – and I can’t tell if his films have gradually worn down my resistance to his kind of fantasy, or if he’s found ways to streamline his art, but for at least an hour or two after I saw it, Moonrise Kingdom was my favourite-ever Wes Anderson film.

The trouble is – and this feeds into a major anxiety at Cannes – the Anderson magic did fade rather fast throughout the day. There’s no doubting the pleasurableness of Moonrise Kingdom, but it didn’t linger or resonate in the way of his edgier early films like Bottle Rocket and Rushmore, because its play-box world is all it wants to give us.

And that switch in assessment is the problem with the instantaneity with which you are expected to evaluate films here. I try to give due weight to circumstance when writing about Cannes because there’s no doubt that screening comfort, for instance, alters the mood of the thousands here. Watching back-to-back director profiles in the small Bazin theatre, with its its air-conditioning permanently set to freezing, cannot be anything but a minor ordeal. Of course this is the moaning of the privileged, but it might have blasted away any cherished afterglow from Moonrise Kingdom.

The absolved

It was almost comical how similarly the two well-constructed hagiographic docs smoothed over the rather similar personal low-points in the careers of Allen and Polanski. Mia Farrow’s discovery of nude pictures of her adopted daughter Soon-Yi in her husband’s possession doesn’t quite match the drama of Polanski’s admission of guilt about having sex with an underage girl, but the emollient tone and tidy apologetic rhetoric of both movies seemed interchangeable. Not that I’m doubting the sincerity of either subject, but these are absorbing films made by friends of the directors, and it shows.

Shifting sands

One question that I’d like hear Thierry Fremaux answer is this: if his defence for the lack of films by women in competition is that he would never select any film simply because it was by a woman – a reasonable stance – why do I suspect he’s picked After the Battle simply because it’s from Egypt, and concerns the Arab Spring? I can’t see any other virtue to justify the choice of this incoherent and clumsy, if well-meaning, piece in the festival’s Competition.

Great expectations

Abbas Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love

Cannes is where all the best directors are, says Geoff Andrew

Web exclusive, 16 May 2012

Cannes – undoubtedly, perhaps now more than ever, the greatest of all film festivals – always arouses high expectations among those heading for the Croisette; mercifully, it also very often fulfils them. That’s mainly, of course, because it consistently appeals to the sales agents and producers of the latest films by the world’s finest directors; how could a festival not excite an enormous amount of interest when it’s the preferred launching pad for the likes of Michael Haneke, Abbas Kiarostami, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, David Cronenberg, Alain Resnais, Walter Salles, Ken Loach et al? And that’s just this year!

So what am I especially looking forward to this time around? It’s perhaps harder for me than for many Cannes attendees to answer that question because, a little atypically, I try to avoid discovering very much about a movie before I actually see it. Since I like to go into each press show with as open a mind as possible, very often the only things I know about a film in advance are its title, its director and – this is absolutely crucial, of course – its running time. But like most, I am swayed by my likes and dislikes regarding the work of certain established auteurs, so no one familiar with my tastes is likely to be surprised if I say that Haneke’s Love and Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love are priorities for me.

But Cannes offers so much and it would be ridiculous if there were not other titles that have particularly piqued my interest. As a long-term fan of Hong Sangsoo, I’m keen to catch Another Country, though the fact that the press screening for that is squeezed between those for the Haneke and the Kiarostami means Sunday might end up providing an embarrassment of riches.

Of the other titles in the main competition, I’m greatly looking forward to You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet! by Alain Resnais; not only does it come highly recommended by an eminent French critic who’s seen it, but I adored Wild Grass when it premiered in Cannes a couple of years ago.

And then, of course, there’s Cosmopolis. I’ve mostly been a big admirer of David Cronenberg’s work from Crash onwards, and this has the added bonus of being an adaptation of a novel by Don DeLillo, an author whose books I respect but sadly can barely get through. However it turns out, Cronenberg will surely have made things easier for me this time around.

Out of competition? I’m extremely curious about Bernardo Bertolucci’s return to directing with Me and You, inevitably eager to see White Elephant by the dependable Pablo Trapero, and very tempted by Le Grand Soir, courtesy of the dependably odd Benoît Delépine and Gustave Kervern. With new films like this to entice me, how on earth could I take time off to lose myself in classics like Hitchcock’s BFI-restored The Ring or the long version of Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America?

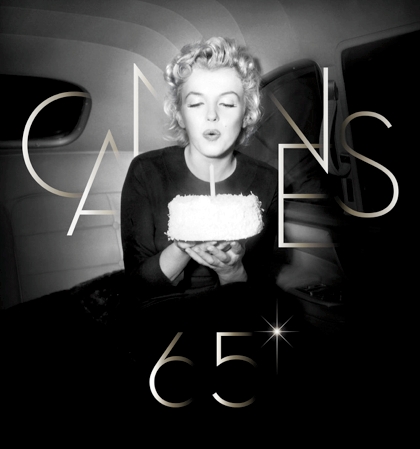

Hello boys

The Festival de Cannes’s 2012 poster

Nick James is on the plane to a man’s man’s man’s man’s Cannes

Web exclusive, 15 May 2012

Welcome to the Sight & Sound Cannes 2012 rolling blog. I hope you enjoy it over the next two weeks. We’ve marshalled a fine bunch of alumni to contribute occasional personal reports from the Croisette and these will be appearing at the rate of at least one per day.

But what can our writers expect this year from what amounts effectively to five programmes – the Competition, Un Certain Regard, the Out-of-Competition and Special Screenings, the Director’s Fortnight (Quinzaine des Réalisateurs) and the Critics’ Week? Last year I was on the jury for the Critics’ Week and saw such fine films as Snowtown, Take Shelter and Martha Marcy May Marlene – and that’s traditionally the weakest strand. Looking down this year’s programmes, my capacity to make sense of all that seems to be on offer is truly boggled, because it looks rich indeed – though it is also courting trouble.

In an editorial just before last year’s Cannes I focused on what I called ‘The Usual Suspects’, the fact that such ‘arthouse’ stalwarts as Pedro Almodóvar, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardennes, Aki Kaurismäki, Lars von Trier and Paolo Sorrentino formed a substantial part of the programme. A glance at this year’s lineup might suggest that feeling will be compounded, with Michael Haneke, Abbas Kiarostami, Walter Salles and Ken Loach all present with exciting new prospects.

However a second glance lets you take in quite how broad is the spread of relatively recently established talent. Cristian Mungiu, Andrew Dominik, John Hillcoat, Jeff Nichols, Ulrich Seidl, Carlos Reygadas, Lee Daniels and Sergei Loznitsa all made their first impact in this century – and Hong Sangsoo and Wes Anderson only just before it – and that’s just looking at the Competition lineup. So the first thing I’m hoping for is some sense of freshness and innovation rather than further refinement of established approaches.

You’ll be reading more than guesswork about the films of these directors soon enough, but one thing you’ll notice is that they’re all men. Nearly every commentator remarked upon this when the Competition list was announced but the issue has now exploded with the publication in Le Monde of an article attacking the festival by Virginie Despentes (Baise-moi), Coline Serreau (Romuald et Juliette) and actress Fanny Cottençon (Conversations with My Gardener).

It adopts a sarcastic tone: “In 2011, probably due to a lack of vigilance, four women featured among the 20 nominees in competition. This year, gentlemen, you’ve come to your senses and we are overjoyed. The Cannes Film Festival will allow Wes, Jacques, Leos, David, Lee, Andrew, Matteo, Michael, John, Hong, Im, Abbas, Ken, Sergei, Cristian, Yousry, Jeff, Alain, Carlos, Walter, Ulrich and Thomas to show one more time that men like depth in women, but only in their cleavage.”

Members of La Barbe, the feminist group behind the protest, are threatening to disrupt proceedings on the Croisette. I could ask what would Cannes be without its annual street-politics angle, but that would be to demean what is a serious complaint. Clearly Lucrecia Martel hasn’t got anything ready to get Cannes off the hook.

So the pleasures of Cannes are likely to be masculine, unless one seeks out the three Un Certain Regard films by Catherine Corsini (Trois Mondes), Sylvie Verheyde (Confession of a Child of the Century) and Aida Begic (Djeca), the Special Screening of Candida Brady’s Trashed, the two in Director’s Fortnight (Noémie Lvovsky’s Camille Rewinds and Yulene Olaizola’s Fogo), and the Critics Week special screening of Alice Winocour’s Augustine. Across five programmes of films it does seem a token representation. It will be interesting to see how the debate manifests itself while we sit in the dark and take it all in.

See also

Cannes Film Festival blog (May 2011)

Women on Film competition for female film writers (Spring-Summer 2011)

Baise-moi reviewed by Ginette Vincendeau (May 2002)